The Responsibility of Accuracy

Historiography and its Relationship with Film and Filmmakers

By Kelly Idali Salaiz

One of the best forms of media to present history has been film. Whether the film’s purpose is to inform, then entertain (Lincoln, 1917, Dunkirk, 42) or to take historical events and create a narrative that is solely to entertain and engage (Troy, 300, The Pianist, Braveheart). Film is visual, fun, and engaging for an audience to watch and “learn” from, but it must be asked to what degree does a filmmaker have responsibility to present a historiographical, accurate final product?

Simplifying History

Filmmakers only have at most two hours and thirty minutes to provide and establish a historical narrative that captivates an audience and (hopefully) informs that audience, which is why holding the attention of an audience, especially during a film can be difficult. In order to do this, filmmakers must simplify history to create the narrative of their film for the screen. But how does simplifying a history to create a filmable narrative affect the position of the historian? Bruno Ramirez has had this dilemma presented to him as a historian and moviegoer and eventually filmmaker.

“Was filmic treatment of the past in itself bound to distort renditions of the past because of the technical imperative that the film (as opposed to the typical historical monograph) imposed?”(Ramirez, 5)

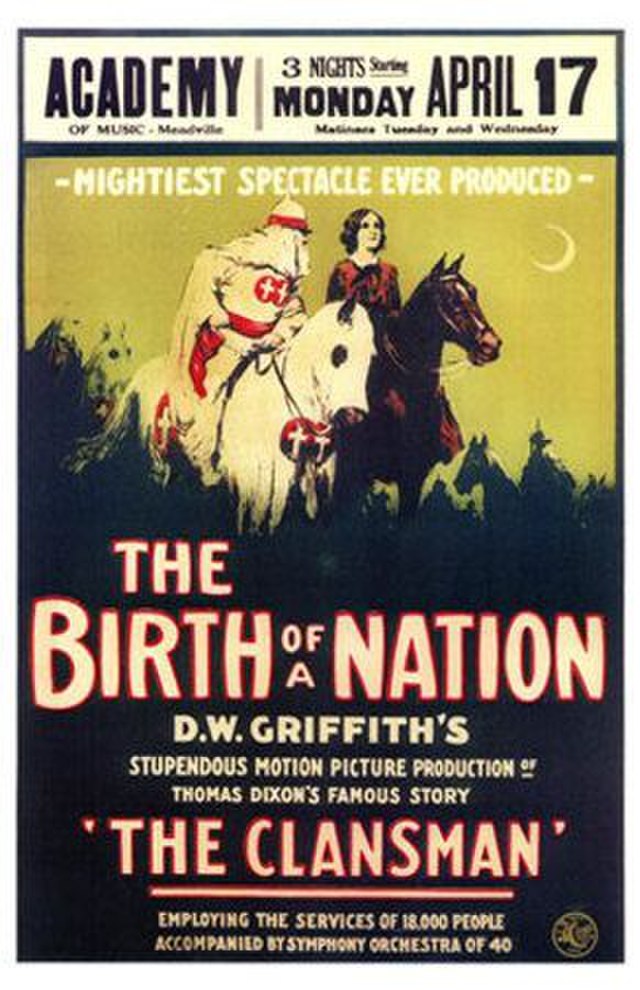

Ramirez’s example of this “filmic treatment” comes from his view of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent epic drama The Birth of a Nation where the movie deals with the Civil War and “heroic” rise of the Ku Klux Klan. This was a film in which Griffith, a filmmaker, not a historian, seemed to want to impart a history lesson of the Civil War, choosing to include battle sequences, political intrigue, and a romantic subplot (because it is a movie after all). As the filmmaker, D.W. Griffith made specific filmic choices such as scenes and sequences with written quotations from historical personalities such as President Abraham Lincoln and contemporary historians such as Woodrow Wilson, while using historically accurate locations pertaining to the history of the film.

Still, Ramirez believed that there were repercussions of the film’s historical theme and treatment of historical narrative that The Birth of a Nation “signaled the irreversible entry of historical motion picture into the American universe of cinema.” (Ramirez, 4) The history was essentially being simplified and diluted by Griffith to create the narrative of an epic Civil War drama that captivated audiences, not really informing as was the filmmaker’s initial intention. So, when does it become the responsibility of the filmmaker to take on the role of a historian?

Filmmakers as the Occasional Historian

It is naïve to think that history is only for historians; history is for all to take, interpret and present. Which is why filmmakers find themselves working in historical films, because the histories are there—but to what degree are filmmakers responsible for providing a historically accurate account? When do filmmakers take on the role of the historian? How do historical narratives present in film offer commentary on contemporary events?

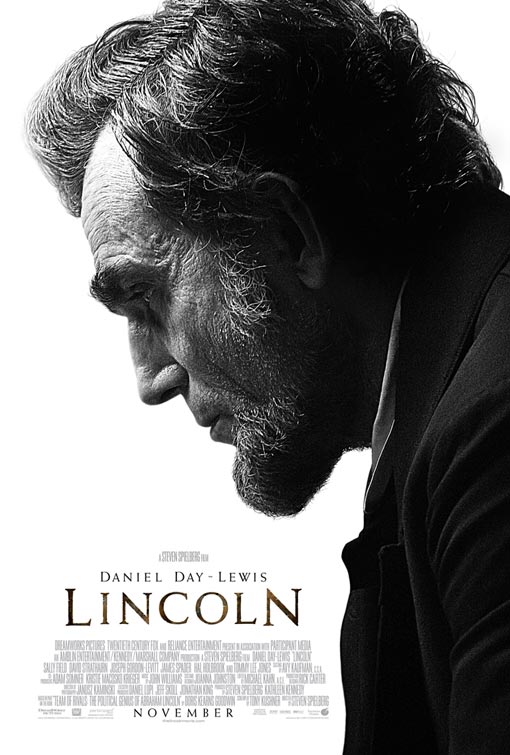

For instance, take the 2013 film releases of Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln; both films centered on slavery, but Tarantino’s film was more of a “play” on history under the guise of a “spaghetti western”, whereas Spielberg’s film was a biographical historical drama about Abraham Lincoln that was serious yet highly revered. (Bonilla, 72) Spielberg was even praised by University of Virginia Professor of History, Philip Zelikow, for “offering new insights” into the Emancipation period of American history, although it was quite apparent that Spielberg had also “silenced” the role of African Americans in that history as well. There was no questioning that Spielberg had gotten the Lincoln side of history correct, but had he done his part as a historian in presenting as much of the history as he could?

What Spielberg was able to do with Lincoln was provide a narrative about Abraham Lincoln, during the Emancipation of slaves, that stays with just President Lincoln, his cabinet administration, and those close to him. On the other hand, Tarantino’s Django Unchained was able to present a fictitious historical narrative about a freed slave who sets out to rescue his wife from a violent plantation owner with the assistance of a German bounty hunter. Where the films differ in their role as historiographic narrative is that Tarantino never wanted to present the film as historically accurate, but more of a “self-conscious meditation on the links between the past and the present” (Bonilla, 74).

Where Spielberg went for an authentic film, Tarantino went for “inauthentic” historical narrative with his film, Django Unchained, because his purpose was to write a film that “speaks to us about the contemporary era of black power.” (Bonilla, 73) Tarantino knew that he was responsible for filming a history that the “political present” set the stage for, and Tarantino was especially aware that “the dynamics of the country are changing, and people are talking about that… This time in history is a part of that conversation.” (Bonilla, 73) Tarantino is aware that he is writing a film, that although perpetuated a western drama, has validity in its history both in the past and in its contemporary. Something that Spielberg was not able to do with Lincoln because although the history is (mostly) accurately portrayed, Spielberg had shortfalls as a historian in not providing the whole history and connecting that history to the contemporary.

“… Tarantino himself is quick to point out, his movie is not ‘History with a capital H.’” (Bonilla, 74)

When it comes to Spielberg’s Lincoln there is an injustice in both historiography and film to exclude the narrative of African American slaves or freemen who were also a part of the Emancipation history. It goes back to Bruno Ramirez’s belief that simplification of history for filmic purposes distorts the rendition of the past. The history being presented is not as accurate as it should be—it is entertaining, informative, but not as informative as it should be to provide accurate representation.

Historiographical Narrative and Agency

Film as a medium is about creating a narrative from the perspective of a filmmaker, whether that be from the screenwriter, director, or producers. Consider the fact that Quentin Tarantino and Steven Spielberg both had films centered around slavery but chose two distinct narratives in which to frame their film. Narrative, framework, paradigm—a historian must be explicit in what they are trying to do with the historiographical work they are presenting for the sake of transparency and agency. An issue that historical narratives will face in filmmaking is the issue of agency and how funding can have implications on production, distribution, and audience; all of which affect content of filmmaking, further affecting the subject of history and what gets to the public.

It has become increasingly important that historians who wish to break into filmmaking are aware of what kind of narrative, framework, paradigm, etc. they are going to work through. For historian filmmakers Barbara Abrash and Daniel J. Walkowitz, the focus on historical narrative presentation became apparent for them while working in public television, creating documentaries for public television, remaining conscious of the fact that “there are historical truths that have profound political consequences.” While working in U.S television, Abrash and Walkowitz realized that there were limits to the types of historical narrative and filmmaking they could present, as “television—including public television—serves corporate agendas far from their own, and that its programming is cast primarily as entertainment” (Abrash & Walkowtiz, 203). They understood that when it comes to the relationship between filmmaking and the role of the historian, telling the “truth” was going to be subjective as it pertained to what medium (public television, mass media consumption as major film releases, independent documentaries, etc.) was presenting that history. Historian filmmakers must ultimately make the decision; sacrifice the historiographical narrative for means of funding and audience, or acquire personal funding and ensure that the historiographical narrative the filmmaker wishes to make is done well?

On top of funding as an issue for the agency of filmmakers, personal and professional agendas also come into play for historical narrative in film. For instance, take biopics and the paradigm that filmmakers must work through when presenting a history of a person; how is the film being funded, and how does the funding of the film affect the context that filmmakers wish to present with the film for both the biopic’s protagonist and their historical, contextual narrative? Filmmakers Barbara Abrash and Daniel J. Walkowitz faced this challenge with their production of Margaret Sanger: A Public Nuisance, a biopic funded by the Independent Television Service of the U.S. public television. The film was “designed specifically to be shown in the context of the reproductive-rights debate” in the 1990s when reproductive rights were under “almost unrelieved siege” (Abrash & Walkowtiz, 211). Abrash and Walkowtiz wanted to create a film that got their message across, even in a contesting environment such as television programming, while “disrupting that environment a bit, by bringing a story from the past into the politically contested present” (Abrash & Walkowtiz, 211).

In the 1990s, filmmakers Abrash and Walkowitz created a narrative film by introducing the history of Margaret Sanger. They were explicit in ensuring that the broader history of reproductive rights was being presented under the filmic narrative of Sanger’s personal story in her own words and point of view while basing the film on “historical record.” While presenting both a big-picture history (reproductive rights in the 1990s) and a small-picture history (Margaret Sanger’s involvement in reproductive rights in the 1910s), Abrash and Walkowitz were intending to “stretch, even violate[s], many of the rules of traditional written history” in order to connect a history from the 1910s to the 1900s (Abrash & Walkowtiz, 212). This was done to “suggest that history is not a thing of the past, safely over and done with—but it resonates and stings in the present,” a sentiment that most filmmakers choose to do to respect both history and contemporary events (Abrash & Walkowtiz, 212).

Entertain, then Inform

Historical movies, such as Lincoln, 1917, Dunkirk, and 47, have been films where the main purpose seems to be entertainment as a form of biographical, historiographic media. But films are flawed, as Hollywood has the tendency to take a sound historical narrative and perpetuate it to make a profit. Author and historian James Reston Jr. has brought up this “tension” between historian and dramatist when “compressing history” to create a narrative to get “what sells and holds the attention of an audience.” Therefore, films like Lincoln, 1917, Dunkirk, and 47 do just enough to inform, then entertain with overly dramatized events, addition of fictional (nonexistent historically) characters, and cinematic elements such as wardrobe, makeup, action, and performance. Holding the attention of an audience is important, but just how much simplification of history harm the overall historiographic significance of the subject?

Historical Narrative and Persuasion

When it comes to narratives, “they are thought to persuade by presenting information in a ‘story format’ such that audience members accept the attitudes and beliefs presented while engaging the story.” (Cui et al, 2743) For instance, take Sophia Coppola’s 2006 colorful historical drama Marie Antoinette, a film whose narrative is highly driven by the excited and “bratty” nature of Austrian-teenager-turned-French-queen. The film is not completely historically accurate, but the filmic treatment of Marie Antoinette made the ill-fated queen likable and tragic. But how could the narrative persuasion of Sophia Coppola’s script compare to the work historians do? Can it be argued that what filmmakers present for historiography is a form of public history.

Historical movies tend to “focus on the portrayal of real events and people,” but historical fiction movies (like Marie Antoinette, Titanic, and Pearl Harbor) “are artistic and creative interpretations of real events [that] struggle with ‘the problem of truth’ because ‘meaning lies not in a chain of events themselves but in the writer’s interpretation of what occurred’” (Cui et al, 2743). Without inherently wishing to do so, filmmakers who create historical fiction narratives are persuading an audience to believe something happened that, although based on some fact, did not entirely happen. It is why there are people who disbelieve that Marie Antoinette, amid a French Revolution, simply laughed at the people and said, “Let them eat cake!” Historical fiction and the movies that are inspired by them are not inherently awful, but can have a revisionist discourse that is ultimately harmful in its “minimization” of history (Bartram, para. 3).

Conclusion

As a medium, film is one of the best ways for history to be accessible to the public. When it comes to the historiographic narrative that filmmakers present, accuracy and transparency should be at the forefront. Still, filmmakers must become the occasional historian so that the final product is presented for (mass) consumption by large audiences in a way that is beneficial for their learning and entertainment. This comes by presenting history as both a story of the past and the present, as Quentin Tarantino, Barbara Abrash, Daniel J. Walkowitz, and many other filmmakers have been able to present through their work. As much as history is both a science and an art, it can be argued that so should the filmic treatment of historiographic narrative.

Bibliography

- Ramirez, Bruno. Inside the Historical Film. 2014: 42-84

- Cui, Di, Zihan Wang, and Arthur A. Raney. “Narrative Persuasion in Historical Films: Examining the Importance of Prior Knowledge, Existing Attitudes, and Culture.” International Journal of Communication (2017): 2741–59

- Abrash, Barbara, and Daniel J. Walkowitz. “Sub/Versions of History: A Meditation on Film and Historical Narrative.” History Workshop, no. 38 (1994): 203–14

- Bonilla. “History Unchained.” Transition, no. 112 (2013): 68

- Bell, Jeffrey A., Claire Colebrook, and James Williams. Deleuze and History. 2009

- Toplin, Robert Brent, and Jason Eudy. “The Historian Encounters Film: A Historiography.” OAH Magazine of History 16, no. 4 (2002): 7–12

- Klenotic, Jeffrey F. “The Place of Rhetoric in ‘New’ Film Historiography: The Discourse of Corrective Revisionism.” Film History 6, no. 1 (1994): 45–58

- Library of Congress, “History & the Movies: An Historian Writes a Screenplay.” Video.

- Jacoby, Faith “Let Them Eat Fake – FHCtoday.Com.”

- Bartram, Erin. “What Is Revisionist History?” CONTINGENT, August 8, 2019.