Byzantine Historiography

Medieval Greek Historiography and Improving the History of Today

By Michael R Aguilar III

Byzantine historiography is a genre of medieval Greek literature which is defined by the writing of history through the course of the medieval Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire. The following seeks to explore the history of this Greek writing of history, chronologically following the individual historians and their works, and giving commentary on them, in order to reveal the general characters of these historians and their works, as well as to give insight into how Byzantine historiography can be used to improve Byzantinist history and historiography, as it is being done today.

The Procopian Era

Byzantine Historians can be classified into various “eras”. The first of these is the earlier, what will be henceforth called the “Procopian” period (~6th-7th c. CE). The Procopian period takes its name from Procopius, who is probably the most significant historian of this period.

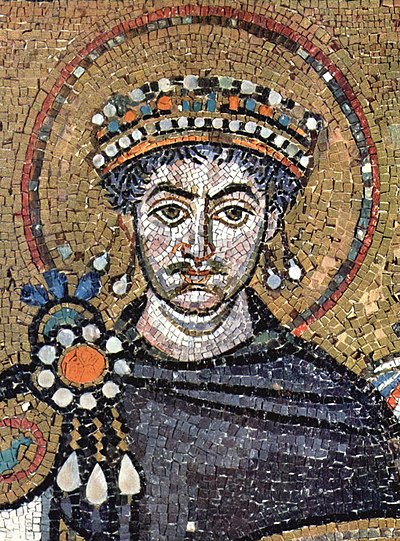

Not only is Procopius significant because he worked from Greece’s existing rich historical traditions embodied in the works of Herodotus and Thucydides, but also because thanks to him we have much documentation of the reign of the Emperor Justinian, which comes primarily from the firsthand experience of Procopius. Justinian was a favorite topic of Procopius’s, and his work on Justinian itself follows a progressive narrative. It begins with a hopeful attitude toward Justinian, but soon devolves into criticism and eventually outright hatred for the emperor (Evans, 219). This all culminates in Procopius’s Secret History, which paints a narrative of the reign of Justinian in vitriolic terms, with chapters having been given titles such as “Proving That Justinian and Theodora Were Actually Fiends in Human Form”, “How All Roman Citizens Became Slaves”, or even more comically “How Justinian Killed a Trillion People”. Despite his obvious bias, Procopius is an invaluable source of information on the reign of Justinian, as it is the most reliable and the most extensive.

Another historian from this Procopian period is a contemporary of Procopius named Agathias Scholasticus (who had also been a poet) and as such, fits firmly into the label of “Procopian historian”, especially being that he had “only included the work of contemporaries” (Cameron, 6). Furthermore, Agathias gives insight into the reign of Justinian from a different perspective, albeit likely less accurately. This lack of accuracy comes from the fact that unlike Procopius, who had been writing from his own personal experiences with the regime, Agathias does so from secondhand oral testimony. Distorting enough as secondhand oral tesimonies are, especially being that Agathias is uncritical of them, he further injects his his own moral biases into the writing, thus distorting the narrative even further. Even so, Agathias is an example of conventional Byzantine historiography, as it was influenced primarily by the Christian environment in which it was written (McCail, 206). This example serves also to solidify the reputation of Procopius, as though he was biased in his own right, he remains the standard to which his contemporaries are compared, as he had the firsthand experience to back up his claim where others did not.

The next, extremely important historian of this period is one Theophylact Simocatta. In a review for Theophylact’s work, the History, Michael and Mary Whitby state that the work is “the most important single source for the last two decades of sixth-century Byzantine and Balkan history and is also indispensable for those years of Sassanian Persian history, namely, the reign of Emperor Mauricius (582-602) (Kaegi, 478).” Being that the History of Theophylact is so encompassing, giving insight into the happenings of three different regions of the world for twenty years, it reaches a contemporary audience with critical acclaim, being regarded as one of the most important primary sources of the late sixth century.

Though it is not traditional historiography in the sense of “history being written about important civil events” (as we will see later), other historians at this time wrote not necessarily about secular matters such as the Byzantine state and its administration, but about religious matters, such as the history of the church. One such historian, and the last one of the Procopian period to be discussed, was one Evagrius Scholasticus, who had written the Ecclesiastical History. This work documents the history of the Christian Church from the year 431 (marked by the occurence of the Council of Ephesus), to the year 594, the year which saw Evagrius’s death. Being that apart from matters of state, religion was seen as the other most important thing to Eastern Roman society, it is fitting that religious histories also be written by Byzantine authors.

10th Century Constantinian Historiography

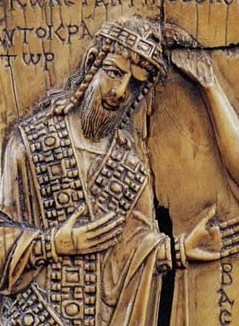

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus is considered today to be a one of the most important Byzantine historians in a time when great Byzantine historians were few and far between. As such, he is the sole figure to be discussed in this section, which is named for him, rather sadly, by default.

Constantine VII is significant in that as historical writing in Byzantium had waned, he had commissioned the assembly of a fifty-three subject collection of the works of Greek authors spanning back to the ancient period. According to G. L. Huxley, “The scholarship of Constantine and of those who worked at his direction was… encyclopaedic: their main purpose was to preserve the learning of the past by making it more accessible.” Furthermore, Huxley credits Constantine VII with preserving “numerous fragments of a universal history by Nikolaos of Damascus, the court historian of Herod the Great”, as well as the work of otherwise lost or unknown historians such as Menander Protector. The preservation of the latter work, called Excerpta de legationibus or the “Excerpts on Embassies”, are according once again to Huxley, “sources of worth for the diplomatic history of sixth-century Byzantium” (Huxley, 30).

The Comnenian Era

This era is named for the first of two imperial dynasties of the Eastern Roman Empire. The first is that of the Comnenus family, and specifically Anna Comnena, the daughter of Alexius I Comnenus (r. 1081-1118), the founder of the Comnenian dynasty. The second is that of the Palaeologus family, the ruling dynasty of Byzantium from 1259 until the fall of Constantinople and Eastern Roman Empire to the Ottomans in 1453.

Anna Comnena’s most significant work is her Alexiad, which accounts the reign of her father. James Seaver, in a review of the work being added to the Penguin Classics collection, calls it “one of the masterpieces of Byzantine literature and history, the biography of the Byzantine emperor Alexius Comnenus… including her famous account of the First Crusade” (Seaver, 28). Therefore, this highly regarded work can be regarded as an example of Greek literature which falls under the genres of both history and biography. Being that the work of Anna is considered so highly, she is likewise in many ways considered to be the “glue” in essence, which holds all of Comnenian historiography together.

Another example of Anna Comnena’s importance is the next Comnenian historian, none other than the husband of Anna Comnena herself, one Nicephorus Bryennius. In fact, besides Anna herself, Bryennius is next the next closest “Comnenian” historian, as the discussion of the two are rather inseperable. For example, in describing Anna’s Alexiad, Ellen Quandahl and Susan Jarratt state the following, “The aim of the work is to record the deeds of her father, completing a history commissioned by Anna’s mother and begun by Bryennius” (Quandahl and Jarrat, 305).The intellectual characters of the husband and wife were one of their most prominent qualities. According once again to Quandahl and Jarrat, John (Anna’s brother and Byzantine emperor) felt threatened by Bryennius as he had viewed “Anna and her husband as a learned and formidable couple, and Bryennius in particular as so powerful” to the point of being particularly threatening in the eyes of John (306). This formidability and power can be attributed less to the fact of Bryennius’s intellectual capabilities and more so to the fact that he was one individual vying for the imperial throne, but Quandahl and Jarratt felt the duo’s combined intellectual capabilities were significant enough to mention as their greatest qualities next to their formidability.

The next of the Comnenian historians to be discussed is one John Cinnamus. Cinnamus is a Comnenian historian insofar as his work is seen as having been supplemental to that of Anna Comnena. According to Paul Stephenson, Anna Comnena largely kept from documenting the actions of her brother John under the reign of their father in her Alexiad. It is known, according to Stephenson, that Anna felt a deal of hostility toward her brother, as she describes him as having been “stupid”, identifying her brother by acknowledging him as the one who had inherited Alexius’s throne. This being the case, the work of John Cinnamus supplements, if only to a small degree, the Alexiad, as it fills in the gaps in knowledge intentionally by Anna Comnena. In fact, Stephenson finds the work so reliable that he calls it “unbiased”, and laments its length by describing it as “all too brief” (Stephenson, 178). It is unfortunate that such a valuable source be so short. However, it does reveal how topics which are covered (or not) by the original author(s) impact perceptions at large about the historical past, as much less is now known about John’s life under Alexius than after his ascension to the throne, thereby potentially diminishing his importance under the reign of Alexius.

A contemporary of Cinnamus is one Niketas Choniates. The most significant work of Choniates is probably his Historia. According to Alicia J. Simpson, it “is the single most important source for the crucial era in Byzantine history that begins with the death of Alexios I Komnenos in 1118 and culminates with the capture of Constantinople by the armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1204,” being the only narrative of the time covering the end of the 12th century, and the only first hand account of what had come next. Furthermore, “the significance of the work as a historical source is equally matched by the insightfulness, sophistication, and stylistic brilliance of its author.” As such, it acts as a main source for scholars today who seek to form a narrative of this time period and these events.(Simpson, 189). As is evident by the words of Simpson, Choniates is an important contributer to Byzantine historical writing. Also being a contemporary of Cinnamus, Choniates fits squarely in the Comnenian camp of historians.

Between Two Eras

A transitionary historian between the aforementioned Comnenian historians and the Palaiologan historians that follow is one George Akropolites. He is a transitionary figure between the two because, according to Anthony Kaldellis in a review of a translation and commentary of Akropolites’s work The History, Akropolites was “a high official of the [Comnenian] Byzantine empire-in-exile at Nikaia [Nicaea] and then of the restored empire under Michael VIII [founder of the Palaiologan dynasty]”. As a historian, once agin according to Kaldellis, Akropolites had written “the most important source for the history of the Balkans and western Asia Minor in the thirteenth century.” Despite this, Kaldellis contends that modern scholarship has paid less attention to this time period and region than others in Byzantine history (Kaldellis, 459). As such, the work of Akropolites serves to shed light on an unfortunately overlooked subject of inquiry, potentially sparking an increased interest into its research. Again, historiography affects the perception of history, as this work of Akropolites, as important as it may be according to Kaldellis, has not done enough to keep modern scholarship interested, thereby possibly creating the idea that the topics it covers are somehow less important than they actually might be.

The Palailogan Era

Impartiality in the writing of history is much more important to modern historians than it was in the medieval Greek east. This is shown through the first truly Palailogan historian, one George Pachymeres. Though he is largely contemporary to George Akropolites, he is labelled here as as “truly Palailogan” because his works deal largely with the Palaiologan emperors, for example, his work De Andronico Palaeologo dealing with Andronicus II Palaeologus. Pachymeres is notable for his impartiality, as it was largely a rarity as far as Byzantine historography goes, being that most of the works described herein are very much biased, either in favor or against, the various figures they discuss. To this end, V. Laurent (having been translated from French), states the following, “George Pachymeres, impartial as much as a Byzantine could be, whose honest face is almost an exception in the gallery of historians of Constantinople, has more than any of his followers suffered from the oblivion and indifference of his compatriots.” By stating this, Laurent is claiming that those who followed in the impartial style of Pachymeres had faced a degree of scorn from their contemporaries. This claim is evident by the discussion of the Byzantine historians featured herein, being that most of them were less than subtle about their biases, and as such were in their time much better received by sympthetic parties.

The next Paloiologan historian is the emperor John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene, who, according to Shaun Tougher, wrote his History as an apologetic work, defending his own actions as the Eastern Roman emperor. This is because “Cantacuzene… can be seen as contributing to the deterioration of the condition of the empire, particularly with regard to his part in two civil wars and his Ottoman policy.” Cantacuzene had two ambitious sons: Matthaios and Manouel. To accomodate their ambitions, he had married his daughter to John Palailogos. This, however, did not work. This move was generally opposed by the Eartern Roman public because it was seen as a betrayal of their sacrifices in war. Furthermore, the Empire under Cantacuzene was lacking in resources and so had to rely on the Ottoman empire, which at the time was growing ever more powerful (McLaughlin, 16-17). Therefore, the History was written to defend these actions. As such, it is obvious that in this writing, some details may have been spared, faults been downplayed, and achievements exaggerated so as to bolster his own reputation with the Eastern Roman public, and for his own personal legacy as a figure subject to the trials of time and history. This again is again goes to show the degree to which impartiality was undervalued in Eastern Roman historiography.

The final historian to be discussed herein is one Nicephorus Gregoras. Gregoras is a contemporary of Cantacuzene, and as such fits firmly into the “Palailogan” camp. As a historian Gregoras is one which represents, at the same time, both traditional and non-traditional approaches to Byzantine historiography. As Teresa Hart describes his work on the Hesychast Controversy, “This work is an example of the traditional school of Byzantine historial writing in that it consists of an introductory summary of earlier history and a much fuller account of events contemporary with the author. But it departs from tradition in that it deals as much, or more, with ecclesiastical as with civil affairs.” In saying this, Hart characterizes traditional Byzantine historiography as having been of practical matters relating to the state, essentially as current events being contextualized by a narrative of the past. This is in contrast with less practical, more theoretical, more philosophical, and obviously more theological, ecclesiastical history.

Byzantine Historiography and Today’s Historians

In sum, Byzantine historiography can be characterized as largely having been biased in favor of one party/faction or figure over another, told in the general form of commentary on what were then civil current events, being contextualized by commentary on past events. Despite this, some historians (though far from the majority) did however, find themselves dedicated to impartiality. Other historians, rather than doing history as is traditionally done, by accounting for important civil, political, or military events in their writing, stuck to a less traditional, but equally important history to Eastern Roman society: ecclesiastical history. Regardless of the particular types or styles of the works written by the various Eastern Roman authors, all of Byzantine historiography has much to contribute to the depth, profundity, and intellectual merit of historiography at large. Furthermore, the scope and expansiveness (or lacks thereof) of the various works of the Byzantine historians have contributed to the degree of attention which has been paid to them by today’s historians. As such, the scope expansiveness (or lacks thereof) may have distorted our perceptions of what events or figures were important then, and which ones were not. Therefore, it is the job of contemporary Byzantinist historians to acknowledge this possibility and work toward minimizing any of this potential distortion. This would provide, for those interested in the history of the Eastern Roman Empire, a more nuanced and potentially more accurate view of this history.

Bibliography

Cameron, Averil, and Alan Cameron. “The Cycle of Agathias.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 86 (1966): 6–25.

Evans, J. A. S. “Justinian and the Historian Procopius.” Greece & Rome 17, no. 2 (1970): 218–23.

Hart, Teresa. “Nicephorus Gregoras: Historian of the Hesychast Controversy.” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 2, no. 2 (1951): 169–79.

Huxley, G. L. “The Scholarship of Constantine Porphyrogenitus.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature 80C (1980): 29–40.

Kaegi, Walter Emil. Speculum 63, no. 2 (1988): 478–80.

Kaldellis, Anthony. Speculum 83, no. 2 (2008): 459–60.

K. G. The Classical Outlook 49, no. 2 (1971): 22–22.

Laurent, V. “Les Manuscrits De L’Histoire Byzantine De Georges Pachymere.” Byzantion 5, no. 1 (1929): 129–205.

McCail, Ronald C. Review of Agathias Assessed, by Averil Cameron. The Classical Review 22, no. 2 (1972): 205–7.

McLaughlin, Brian. “An Annotated Translation of John Kantakouzenos’ ‘Histories’, Book III, Chapters 1-30,” 2017.

Procopius. Secret History. Translated by Richard Atwater. University of Michigan Press, 1963.

Quandahl, Ellen, and Susan C. Jarratt. “‘To Recall Him … Will Be a Subject of Lamentation’: Anna Comnena as Rhetorical Historiographer.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric 26, no. 3 (2008): 301–35.

Scholasticus, Evagrius. The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus. Translated by Michael Whitby. Liverpool University Press, 2001.

Simpson, Alicia J. “Before and After 1204: The Versions of Niketas Choniates’ ‘Historia.’” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 60 (2006): 189–221.

Stephenson, Paul. “John Cinnamus, John II Comnenus and the Hungarian Campaign of 1127-1129.” Byzantion 66, no. 1 (1996): 177–87.

TOUGHER, SHAUN. History 82, no. 266 (1997): 297–98.