Medieval Russian and Tsarist Historiography

An Overview of Historical Thinking during the Early Medieval Period to the Early Modern Period of Russia

By Christopher Beaudet

(October 16th, 1852- September 21st, 1916) *The Baptism of the Kievans* done in the realism style of painting. The painting reflects the story of Vladimir the Great and the conversion from slavic paganism to Orthodox Christianity.](

/metahistory/essays/images/beaudet-lebedev-baptism.jpg

)

The histories and legacy of Russian historical thinking are largely unknown to American and most other western audiences lending themselves to popularized myth and superstition. However, Russia’s birth and development mirrored much of Western Europe in the medieval ages and had strong intellectual institutions. The period of Mongol control over the Russian principalities forever changed the trajectory of Russian civilization, culture, and governance. This is reflected by various historiographical and history pieces written throughout Russia’s medieval and early tsarist periods.

Of Rus’, Slavs, and the Rurikids

Before the landings of the Varangian Rurik and the establishment of the Kievan Rus’ under his successor Oleg the Seer in the 9th Century, the lands east of the Baltic Sea and north of the Black Sea were inhabited by various Slavic tribes. In the northern regions of modern-day Russia and Belorussia, lived the tribes of the Ilmen Slavs (Novgorod), the Krivichi (Polotsk), and the Chuds (Staraya Ladoga and Karelia) (Rukavishnikov 60). In the southern regions of modern-day Russia and Ukraine lived the Polians (Kyiv), the Drevlians (West-Bank Dnieper), and the Severians (East Dnieper and the Danube). In the middle of these two regions, around the Oka River and the Don, lived the Vyatchi.

, the Principalities, and the various Slavic tribes. The various principalities of the Rus' make up the single largest medieval polity led by Kyiv.](

/metahistory/essays/images/beaudet-principalities-of-the-kievan-rus.jpg

)

The 9th Century saw expansion, conquest, and settlement all around Europe by Scandinavians. The Varangians first arrived in Novgorod in 859 A.D. and were subsequently expelled three years later by the tribes of Novgorod, Ladoga, and Karelia. However, the vacancy of power left by the expelled Varangians caused the tribes of the area to war with each other. After a short term of chaos, the tribes of Novgorod invited the Varangians back to rule, and with it came Rurik and his brothers. Rurik’s brothers died shortly after, and Rurik consolidated the lands of Novgorod which became known as the lands of Rus. This began one of the longest-ruling dynasties of Europe, the House of Rurik. This dynasty will see the expansion of the Rus’ to Kyiv and the birth of the Kievan Rus’ under Rurik’s successor Oleg in 882 A.D. (Rukavishnikov, 64) The Kievan Rus’ will fragment into various principalities in the north and south to later be destroyed by the Mongols in the 15th century.

During the fragmentation period of the Kievan Rus in the 12th century, various north successor states started forming such as the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal which gained independence in 1157 A.D. The city of Vladimir was sacked by the Mongols in 1238 A.D. and eventually was vassalized by the Mongols. Under Mongol rule, The Grand Principality of Vladimir along with other Rus’ principalities began to be ruled from the city of Moscow and later transformed into the Grand Principality of Moscow (Kuznetsov, 792). The Duchy became the progenitor state of Tsarist Russia, the Russian Empire, the United Soviet Socialist Republics, and the Russian Federation. The resulting histories and narratives produced in these varying political periods sought to establish the legitimization of various states, create common identities among the people, and demonstrate the power of the reigning monarch.

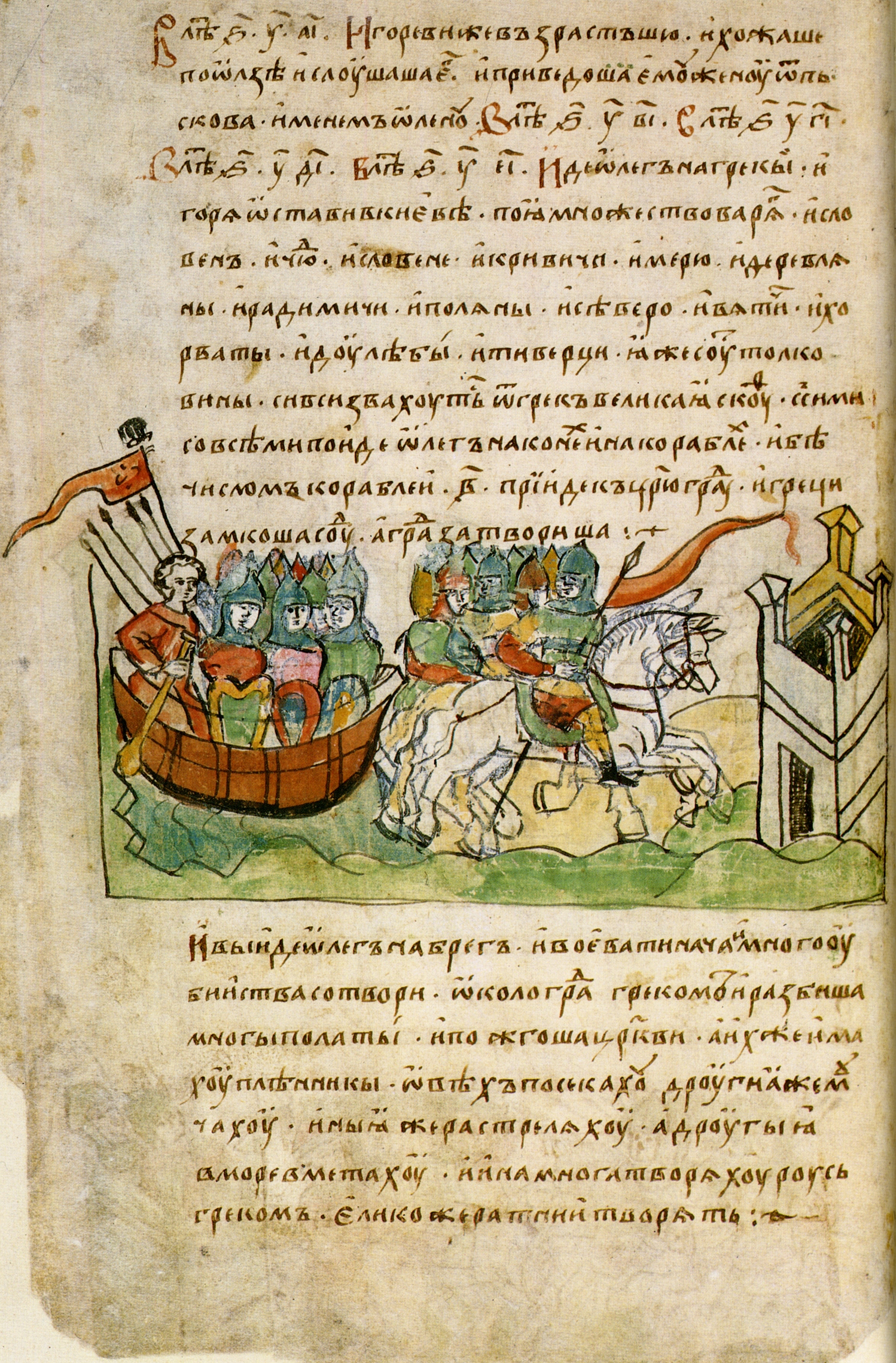

The Tale of Bygone Years

The Tale of Bygone Years, as it is known in angalcized Old Slavonic, or the Primary Chronicle, as it is also known, is the oldest surviving manuscript of the Kievan Rus’. This work was compiled by the Hegumen Saint Nestor the Chronicler of Kyiv and tells the collective history of the Kievan Rus’ from a Christian perspective (Rukavishnikov, 54). The Primary Chronicle is the most important manuscript of the Russian early medieval period amongst other East Slavic nations. The Primary Chronicle is also the first historical text compiled in Russia, indicating the birth of medieval historical writing during this period.

Nestor the Chronicler was a central figure in the creation of the Primary Chronicle. He was responsible for several works including Life of the Venerable Theodosius of the Kyiv Caves and Account about the Life and Martyrdom of the Blessed Passion-Bearers Boris and Gleb. Nestor was a learned man and was acquainted with the historian John Malalas and George Hamartolus of the Byzantine Empire, despite his distaste of Greek influence in the Rus’. Nestor’s writings convey a Slavonic paradigm of Russian history which reinforces the idea of a historical unity of the Slavic peoples (Kola, 150).

The Primary Chronicle starts with stories from the Book of Genesis, commonly known as the Deluge (Rukavishnikov, 55). The purpose the Chronicle places on these stories is to establish a comprehensive story from the time of the creation of the Slavic peoples. Following the story of creation, the Chronicle provides a narrative of the start of the Rurikid dynasty and how it came to power to legitimize the current ruling house of the Kievan Rus’ as the sole legitimate one. The purpose of emphasizing the line of the Rurikid princes follows a need for unity amongst the various Slavic princedoms. At the time this text was compiled, the Kievan Rus’ began a long period of infighting and political weakening of the authority of Kyiv.

There exists in the Chronicle other historical narratives, such as the murder of Askold and Dir by Grand Prince Oleg, which provides an idea that the conquering of Kyiv was for justice (Rukavishnikov 61-62). Also included was the vengeance of Saint Olga, then regent of her son Sviatoslav I (r. 945 A.D. to 960 A.D.), who subjugated the Drevlians tribe after they murdered her husband Grand Prince Igor (Rukavishnikov 62). It is also learned from this chronicle the accounts of Saints Cyril and Methodius and the birth of the old Cyrillic alphabet.

Also included in the chronicle is the tale of Saint Vladimir the Great, grandson of Olga, who converted the Slavic Princedom of the Kievan Rus’ to Orthodox Christianity. This tale includes a story about Vladimir’s choosing of religion for the Rus’, discerning and asking for representatives from Islam, Latin Christianity, and Greek Christianity. Some thought exists that the choice of Greek Christianity for the realm of the Rus’ was pragmatic given the proximity of Byzantium and the Patriarch of Constantinople to the Rus’ as opposed to the distance of the Pope in Rome. According to the tale, Islam was rebuked due to the prohibition of alcohol consumption as a tenet of religion. The tale of the conversion of the Rus’ is central to the Orthodox identity in the Rus’ and is used to legitimize the autonomy of the Russian church to the modern-day.

Debate exists on the accuracy and the extent of Saint Nestor’s authorship (Rukavishnikov, 55). It is theorized that Nestor did write some of the Chronicle, but also compiled information from various sources to produce this work. The account also provides some factual errors in dating that lend themselves to scrutiny.

Chronicle Editions of the North and South

While the polity of the Kievan Rus’ still existed, it ceased to be a unified state around 1130 A.D., a couple of decades after the publication of the Primary Chronicle. Since the founding of the Kievan Rus, local principalities had developed their Chronicles, tailored to the individual histories of their respective princes and peoples. One such example of local history is the Novgorodian Chronicle and its several editions which focused on the documented foundation of republicanism that founded the Novgorod Republic in northern Rus’ (Guimon, 105-106).

Other historical narratives that existed at the time were the Laurentian Codex and the Hypatian Codex. The Laurentian Codex, authored by a monk named Laurentius, mainly included compilations of Chronicles in Northern Russia, primarily around the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal. This edition included the second edition of Primary Chronicle, edited by the Hegumen Sylvestyr, and the continuation of recorded history from that point (Rukavishnikov, 56). The codex was a central historical piece to the formation of the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal and later the Grand Duchy of Moscow. This piece is used to legitimize the rule of the Rus’ by the princes of the north and their claim to the legacy of the Kievan Rus’. The northern states will contribute to the formation of what will eventually be known as modern-day Russia.

The Hypatian Codex consists of the Primary Chronicle, the Kievan Chronicle (post-fragmentation), and the Galician-Volhynian Chronicle. The codex was compiled around the early 15th century and was discovered at the Hypatian Monastery in Kostroma in the 18th Century. The codex contains the only surviving manuscript of the Galician-Volhynian Chronicle. The codex of Hypatia centers around the histories of the southern Rus’ and legitimizes the line of the rulers of the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia and their claim to the legacy of the Kievan Rus’. The histories of the Hypatian Codex will contribute to the identity of modern-day Ukraine.

The Tatar Yoke

In 1237 A.D., the shell of the Kievan Rus’ was conquered by the Mongols, led by the grandson of Genghis Khan, Batu. The infighting of the Rus’ princes and their desire to see their rivals fall to the Mongol Horde allowed the 250-year epoch of Mongol rule over the lands of Rus’, known as the Tatar Yoke. The Mongol conquests of Russia were brutal and destroyed the once great cities and culture of the Kievans.

(June 11th, 1970- July 16th, 2014) [*The Battle of the Kalka River*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Kalka_River) Illustrates the largest military death blow to the Kievan Rus' which allowed further mongol incurrsions into Rus' Territory.](

/metahistory/essays/images/beaudet-battle-of-the-kalka-river.jpg

)

The conquest of the Rus’ was a setback in the economic and literature development of Russia. Whole cities and towns, such as Ryazan, Tortzhok, and Kozelsk had their populations eradicated through murder or slavery (ÇİÇEK, 97) The Tale of the Destruction of Ryazan describes the carnage the Rus’ people endured, yet provides a perspective from Russians at the time, that this time of suffering was punishment for their sins. This idea of divine punishment is a common historical narrative that exists throughout Russian historical thinking during this period as is a traditional school of thought that persists through the Imperial period (ÇİÇEK, 98-99).

The Tatar Yoke created a period of isolation, that focused the conquered Rus’ away from western Europe and more into the affairs of Asia (ÇİÇEK, 102). Rus’, already blended from the traditions of the Scandinavians, Byzantines, and Slavs, became infused with the governing traditions, language, and culture of the Mongol Empire.

It is during the Mongol period where Moscow, a city in the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal, begins its rise to power as the Mongol Khanate of the Golden Horde chooses the Prince of Moscow in 1328 A.D. to enforce Mongol tribute. The center of this Orthodox Church in Russia will also see itself move to Moscow in 1322 by Metropolitan Petr. (ÇİÇEK, 101) The rise of Moscow amidst the backdrop of Mongol inner conflicts sets the stage for the future of Russia and its historical narrative.

Historical Narrative of the Third Rome and Holy Rus’

During the 15th century, the Grand Principality of Moscow became the preeminent power in the lands of the northern Rus’ and began to eclipse other Rus’ Principalities including its Mongol overlord, the Golden Horde. In 1480, Moscow finally achieved independence from the Tatar yoke when Grand Prince Ivan III took the Great Stand on the Ugra River and the retreat of the Tatars from Rus’ lands (ÇİÇEK 97). Under Ivan III, the territory of Moscow expanded, especially after Ivan conquered the northern Novgorod Republic which saw Muscovy grow into northern Karelia and bordered the White Sea. After he absorbed all his rivals, he crowned himself “Grand Prince of all Rus’” and began referring to himself, although informally, as Tsar.

Previously, an international political crisis was growing in southeastern Europe when Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople on May 29th, 1453 (Naydenova 39). The remaining members of the former reigning Palaiologina family of the Byzantine Empire disbursed into western Europe, including Sophia Palaiologina. At the suggestion of Pope Paul II in 1469, who hoped to unite the Western and Eastern churches with Orthodox Russia, a proposal was made to Ivan III to marry Sophia. Ivan III accepted not for ecclesiastic reconciliation, but for the rights, Sophia had to Constantinople. Through this marriage, Ivan adopted the idea of Moscow as Third Rome and incorporated the double-headed eagle, once associated with Byzantium, as the new arms of Moscow.

Two important historical legends came about after the death of Ivan III in 1505 A.D. One was a treatise developed by an unknown author named The Tale of the Princes of Vladimir (ca. early 16th Century), and the other was a story recorded by the monk Philotheus of Pskov named The Legend of the White Cowl (ca. 1510). Both narratives at the time reinforced the idea of Moscow being the Third Rome, a successor of Constantinople (Wieczynski, 320).

The political-historical narrative, The Tale of the Princes of Vladimir asserted that the line of the Rurik Dynasty extended past Rurik to a mythical figure named Prus who was given the northern part of the world by the Roman Emperor Augustus. The treatise allowed the later Tsar Ivan IV to claim the heritage of Rome and declared himself formally Tsar of All Rus’.

The idea of Holy Rus’ and the succession of the authority of the Christian church being relegated to Moscow is a theme present in the historical narrative The Legend of the White Cowl (Wieczynski, 320). The legend describes the journey of a holy relic, a white cowl, and its ownership from Rome, to Constantinople, and finally to Moscow. Although this legend was later condemned by the Moscow Synod of 1667, it can be extrapolated that the symbology of earthly Christian authority was the cowl, and the fact that it rested in Moscow can only infer the Primacy of the Russian church in the Orthodox Christian world. In 1589, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremias gave Autocephaly. Autocephaly is the ecclesiastical recognition of a Patriarch as co-equal to and autonomous from other orthodox churches to the Russian church which further cemented the idea of Third Rome successorship. The idea that Russia was holy land is reflected in the 15th to 16th centuries and carries on in some form to the modern-day (Naydenova, 44-45).

Ivan IV the Formidable and Early Tsarist Russia

As opposed to the decentralizing narratives of the late Kievan Rus’, the reign of Tsar Ivan IV the Formidable saw a centralizing historical narrative aimed towards legitimizing the new state of Russia. It is during Ivan IV’s reign that the Grand Duchy of Moscow transforms into the Tsardom of Russia. The idea of the Third Rome provided important ideological context for the development of two official historical narrative texts: The Illustrated Chronicle and the Book of Royal Degrees. The goal of these narratives was to legitimize the new Tsarist state and Ivan’s reign with an orthodox Christian bias (Lenhoff, 338).

To solidify Ivan’s lineage and his claim to the throne of Russia, the Moscow Metropolitan Macarius commissioned the Book of Degrees. This book is the first Historiographical text produced and sanctioned in the Tsardom and made official the historical narrative of the Third Rome towards Ivan’s coronation. Elements of this book are borrowed from the treatise Tale of the Princes of Vladimir such as the genealogy of the line of Rurik extending to Caesar Augustus. The text of the book utilizes orthodox hagiography, extolling all rulers in the book as saintly. This falls in line with the historical narrative the orthodox church wished to push however the creation of this project was subsequently halted in 1520 (Lenhoff 338).

Ivan IV commissioned the Illustrated Chronicle for his royal house and education within the Royal family after he instituted the Oprichnina, Ivan’s state within a state (Lenhoff, 337). As a result, the Illustrated Chronicle became the largest collection of historical manuscripts in late medieval Russia. The work encompasses the history of the world as it relates to Russia from Biblical times to the classical era, incorporating Byzantine history, and relating it all to Russian history in that period. This work excludes the count of royal generations of Ivan but contains separate entries for each. This body of work maintains these collections in chronological order and is considered an annalistic work.

The separate works of the Book of Degrees and the Illuminated Chronicle correlate to different periods of Ivan’s reign. This seems to reflect Ivan’s growing paranoia and distrust of the ruling elite of Russia, the boyars. Whereas the Book of Degrees seems to be an important church work consistent with past works such as the Nikon Chronicle that extols rulers and their characteristics, the Illuminated Chronicle, and its construction was mostly archival and limits such expression (Lenhoff, 343). It is entirely possible because Ivan sought to isolate himself from his political enemies, that this historical work may have been a deliberate attempt to downplay their contributions or isolate them historically in this work.

Ivan’s later reign during the Oprichnina created instability within Russia. Ivan engaged in wars with Poland-Lithuania and killed his most capable heir to his throne, Ivan Ivanovich. Ivan produced works that sought to legitimize his actions and attack his enemies, such as the Synodal Codex and the Book of the Tsardom, which Ivan may have had a hand in creating personally (Lenhoff 343).

The death of Ivan presented a precarious position for the new Russian state as Ivan’s successor, Fyodor Ivanovich, died heirless and rendered the Rurik dynasty extinct. From this point, Russia was subject to a series of succession crises, invasion, and occupation by Poland that is known as the Time of Troubles. The rise of a new dynasty that would last until 1917 A.D., the House of Romanov, would come towards the end of the Troubles and see Russia on a future path of modernization and rise as a global power.

Conclusion

The various historical works produced throughout medieval Russia and into the early modern period led to the creation of what we know as Tsarist Russia. It is in these historical documents where the reinforced identity of orthodox Slavic peoples is tied to the future of the Princes of Rus’. Despite the factual dubiousness of certain sources, the histories produced from these periods provide a glimpse at the thought and beliefs of these peoples. It is these various historical narratives that provide a clear picture of the historical thought of medieval and early tsarist Russia.

Bibliography

Kuznetsov, A.A. Кузнецов, А.А. “Yelementui Imperskoi practiki vo vneshneii politikye vladimirskovo knyazhestva pervoii treti XIII veka” ЭЛЕМЕНТЫ ИМПЕРСКОЙ ПРАКТИКИ ВО ВНЕШНЕЙ ПОЛИТИКЕ ВЛАДИМИРСКОГО КНЯЖЕСТВА ПЕРВОЙ ТРЕТИ XIII ВЕКА [The Elements of Imperial Practice in the Foreign Policy of Vladimir Princely State in the First Third of the 13th Century]. Uchenuiye zapicki kazanckovo universityeta. seria gumanitarnuiye nauki УЧЕНЫЕ ЗАПИСКИ КАЗАНСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА. СЕРИЯ ГУМАНИТАРНЫЕ НАУКИ 159, no. 4 (2017):791-808

Erusalimskii, Konstantin. 2012. “The Book of Royal Degrees and the Genesis of Russian Historical Consciousness.” Kritika: Explorations in Russian & Eurasian History 13 (3): 725–35.

Guimon, Timofey V. Гимон, Тимофей Валентинович, “Letopisaniye I razvitiye picmennoii kulturui (Novgorod, XI-pervaya polovina XII v.)” Летописание и развитие письменной культуры (Новгород, XI-первая половина XII в.) [Annalistic Writing and the Development of Written Culture (Novgorod of the 11th and the First Half of the 12th Centuries)]. Slovēne no. 1 (2015): 94-110

Kola, Adam F. 2017. “The Primary Chronicle in Light of World(-)System Theories and Social Constructivism.” Russian History 44: 150–71.

Lenhoff, Gail. 2016. “The ‘Book of Degrees’ and the ‘Illuminated Chronicle’: A Comparative Analysis.” Revue Des Études Slaves 87 (3/4): 337–49.

Magaril, Sergei. 2012. “The Mythology of the ‘Third Rome’ in Russian Educated Society.” Russian Politics and Law 50 (5): 7–34.

Naydenova, Natalia. 2016. “Holy Rus: (Re)Construction of Russia’s Civilizational Identity.” Slavonica 21 (1): 37–48.

Rukavishnikov, Alexandr. 2003. “Tale of Bygone Years: The Russian Primary Chronicle as a Family Chronicle.” Early Medieval Europe 12 (1): 53–74.

Wieczynski, Joseph L. 2000. “The Legend of the Novgorodian White Cowl (Book Review).” Catholic Historical Review 86 (2): 319–20.

Çìçek, Anil. 2016. “The Legacy of Genghis Khan-The Mongol Impact on Russian History, Politics, Economy, and Culture.” International Journal of Russian Studies, no. 5: 94–115.