Medieval Islamic Historiography

By Eden Vigil

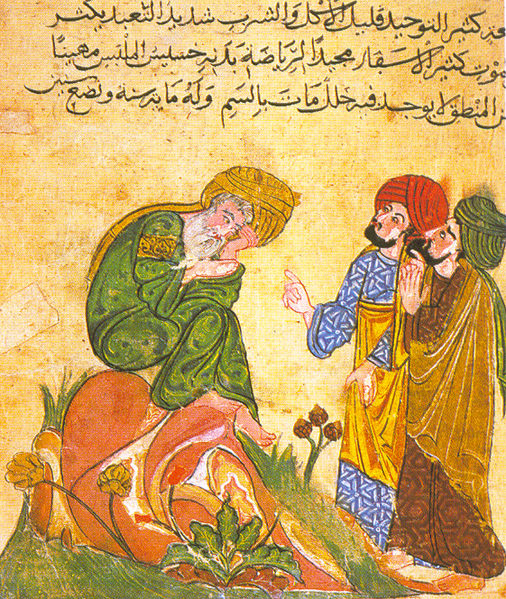

Middle Eastern scientific and cultural achievements have traditionally been ignored by Eurocentric Western academia, and Middle Eastern historiography has accordingly been excluded from the traditional historiographical narrative. The sources most commonly used for Historiography classes focus almost exclusively on Greco-Roman and European historiographers, and this section hopes to include a medieval Middle Eastern perspective. This essay is going to focus on three historians and their methods of writing history: al-Ṭabarī, ibn al-Athīr, and ibn Khaldūn from the 10th-14th century. These three Islamic historians are often unrepresented in the historiographical narrative, yet they all offered unique contributions to the way medieval Middle Eastern history is understood today. These historians’ works were both foundational and exceptional within the writing of history. Without their contributions to the writing of Islamic history, its narrative would likely be rather lackluster.

The importance of Islamic historiography in the Western narrative is seen throughout each historian’s contributions. They prove that the way Western historiography had developed was not unique or inevitable. The use of narrative and relying on religion to explain events was seen–not only in Medieval Islamic writing–but in medieval Christian chronicles and history as well. This is seen in al-Ṭabarī’s History of the Prophets and Kings Later in the medieval period, the analysis of social structures and institutions to form a historical narrative was being done by fourteenth century in Mosul, despite this technique not being used in Europe until the 20th century with the creation of the Annales schools. This development poses an answer to the supposed deficiency of Islamic historiographical perspective. The three authors who are the focus of this essay are considered to be the three historiographical founders and replicators of a Greco-Islamic approach and narrative of causation. In their three different works, they each attempt to answer the question of historical consequence. Each historian had a large framework in which they worked. They cannot be removed from their timeline, but with the perspective of historical hindsight, their importance to our understanding of historiography becomes clearer.

Middle Eastern history has been primarily rooted in the Islamic faith, and often begins with the Islamic account of the creation of Adam. From the advent of Islam, or its consequent golden ages after the 7th century, history was told in a narrative form. As such, it consisted primarily of stories which were “used to help the listener [or] reader frame the historical narrative that he or she was about to hear [or] read” (Keshk 2009, p. 382). It helped to “frame” the narrative which was done in three different ways. The first way is through familiarity; “the…story follow[s] a certain pattern than the listener/reader is familiar with.” The second way “is to use the set-up story as a moral micro-narrative of what is about to occur.” It then acts like a frame for the narrative. Finally, the third way to “set-up” the story is as a lead-in; “that is, the narrator would like the listener/reader to understand the protocols of certain actions” (Keshk 2009, p. 382). These frameworks for Islamic history posed as a way to illuminate the aspects unique to it.

The first Islamic historian to be discussed here is Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (839-923 CE). He was a Persian scholar who wrote on a variety of subjects aside from history, such as interpretation of the Qu’ran, law, language, and mathematics. His major historical work The History of Prophets and Kings was the first Islamic historical work of its kind (Osman 2001, p. 66). al-Ṭabarī utilized different sources in his recounting of history; he included “a basic chronological framework and an outline of the main events… that were matters of widespread and generally accepted knowledge” (Osman 2001, p. 67). In other words, it was similar to a chronicle, with the date and the daily happenings included. The style al-Ṭabarī wrote has been described as “the khabar-form” of writing history.

Khabar or the plural akhbar often is translated as modern-day news or happenings, but in this case it means individual reports (Mårtensson 2005, p. 291). This term describes the histories written from the eighth to the ninth centuries CE that were written as narratives that were “pieced together by individual reports about historical events, transmitted by isnads, or the chains of authorities…” (Mårtensson 2005, p. 291). Within these narratives, the information was received by the isnads and was presented to the writer. Al-Ṭabarī then gave variants to the information they gave him, evaluating it with “his main criteria of evaluation being soundness of the isnad, and reference to God and His Messenger” (Mårtensson 2005, p. 292). This means al-Ṭabarī wrote his history from the information provided by a religious authority then incorporated it in work using narrative. This theme of an authority transmitting the historical narrative has been seen time and time again throughout the textbook; this is not the last time it will be mentioned either.

Within his transmission of the information from the isnads, al-Ṭabarī often “interjects and inserts general information that was presumably circulating at the time”, thus creating “a basic chronological framework and an outline of the main events… that were matters of widespread and generally accepted knowledge” (Osman 2001, p. 67). However, al-Ṭabarī has also been accused of manipulating the sources in order to fit his narrative. This is not unique to al-Ṭabarī; many medieval scholars did this with documents of antiquity to fit a religious narrative (Popkin 2016, p. 39). For example, “al-Ṭabarī added material to his sources to develop the characters of his heroes and villains. In others, he omitted details to render characters who were not central to his theme more opaque.” (Judd 2005, p. 210). al-Ṭabarī also “recorded…different versions that sometimes confirmed and sometimes contradicted each other” (Gabrieli 1979, p. 86). This was a consequence, at least in part, of a lack of peer-review. Overall, the utilization of the khabar-form to create a thematic narrative to explain events was not limited to just al-Ṭabarī. His historical successors also utilized narrative, and his legacy lived on through ibn al-Athīr.

Chronicler of Salah ad-Din, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, ʿIzz al-Dīn Abū al-ḤasanʿAlī ibn al-Athīr (1160-1233 CE) wrote an entire world history called Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh or The Complete History. This history, like many others from the Islamic world, began with the Islamic account of the creation of Adam and continued up to time contemporary to the author. Ibn al-Athīr’s methods included the application of a title and placing events in chronological order (Kamaruzaman et. al 2015, p. 32). While this was not unique to ibn al-Athīr, it helped the work remain organized. His contribution continued a unique genre of “complete” historical writing.

Ibn al-Athīr’s work in The Complete History includes an introduction, or muqaddimah in Arabic. This introduction includes “his philosophy of history for collective understanding of the readers” (Kamaruzaman et. al 2015, p. 29). His work was not purely a “historical” artifact, but was also intended to be a reminder to mankind, or a tazkirah. (Kamaruzaman et. al 2015, p. 32). His work was both universal and contemporary, because it focused on both important Islamic events and minor (non-Islamic) events. Self admittedly, he did borrow from historians before him and stated that “the source of al-Kamil was the work of history by Abu Ja‘afar al-Tabari namely the book Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk” (or History of Prophets and Kings) (Kamaruzaman et. al 2015, p. 31). His historical analysis has been vital to the understanding of the Crusades. While his work revolved around the conflicts between Saladin and the European Crusaders, the history he wrote was not limited to just his personal experience: he “did not limit his attention to events that involved them; he had wider horizons [and included] North African history…as well as accounts of events in Central Asia and Iran” (Hillenbrand 2008, p. 712). Al-Athīr’s The Complete History is a grossly overlooked and underrated piece of historical writing, and while his methods were questionable, his contributions to the writing of history cannot be downplayed.

Ibn al-Athīr’s writing directly opposed the way in which other Islamic historians of his time (and before him) wrote. For example, other Islamic historians did not focus on an area beyond their geographical location and many historians did not “extend to record events in other areas” (Kamaruzaman et. al 2015, p. 30). However, a wider scope of historical interest does not necessarily mean a completely accurate portrayal of the past. He “frequently suppresses elements of the original narrative, and occasionally uses the rest to support a false interpretation” (Gibb 1935, p. 746). While his work was revolutionary at the time because of the scope, it still cannot be taken at face-value as a “sole authority” (Gibb 1935, p. 751). This is important to remember for all works of history and thus, the purpose of historiography.

.jpg

)

The last historian that will be discussed herein is the Tunisian-born Abū Zayd ‘Abd ar-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Khaldūn al-Ḥaḍramī (1332-1406 CE) better known as ibn Khaldūn. His work the The Muqaddimah which is the first volume, and an introduction to, his world history “the Kitab al-‘lbar” or Book of Historical Examples (Gabrieli 1979, p. 93). He was trained in philosophy and often wrote “some summaries of the works of great Muslim philosophers”, but never called himself a philosopher (Çasku 2017, p. 27). In fact, Ibn Khauldun “did not only criticize philosophy but also refuted it and condemned those who taught the subject” (Ahmad 2017, p. 58). He was never in the “circle” of Muslim philosophy, nor was The Muqaddima a strictly philosophical introduction to history; however, his introduction holds to both Greek and Annaliste styles of writing (Ahmad, 2017 p. 57, 58). The Muqaddima is “a general review of the arts, science, and industry of Islamic civilization” which is a predecessor to the history of the people “with ethical and cultural stratification” (Gabrieli, p. 93). Within The Muqaddima, ibn Khaldūn creates the concept of ‘aṣabiyyah, or sense of social cohesion/solidarity in relation to civilization.

Ibn Khaldūn’s main theme within The Muqaddima is this concept of ‘aṣabiyyah. This contrasts with civilization, the latter being defined as “the matter of the state”. Conversely, “the state provides matter for civilization”, which is the potential material cause of history (Çasku 2017, p. 34). ‘Explained in more detail, aṣabiyyah is the “family or group feeling, whose intensity varies with environment.” (Dale 2006, p. 438). It replaces one’s “destructive tribal and kinship ties” (White 2009, p. 236). However, just as relationships end or family members pass away, ‘aṣabiyyah, naturally, also has an end. Like the end of dynasty, individual civilizations pass away as well. This change is done without human agency because “[the] kingship arises because of the “necessity of existence, [or] darufra al-wujud”. So, just as civilizations form with ‘aṣabiyyah, kingships form because of “the necessity [their] existence” (Dale 2006, p. 438). The theory of historical causality is present within his works, utilizing rationality and logic. This is why he has often been called the last Greek and first Annaliste Historian.

Ibn Khaldūn has been called “the last Greek and the first Annaliste Historian” because of this large introduction, in which he “used the…assumptions of this rationalist tradition” (Dale 2006, p. 431). The way in which this was implemented within The Muqaddimah was by Khaldūn simply stating that “history is–or should be–rooted in wisdom or philosophy” and that the past must be analyzed, rather than reported. This was to be done “rationally… using Greco-Islamic logical methodologies” (Dale 2006, p. 433). The introduction alone contains his “philosophic ideas, with regards to human society, history and civilization,” so it has been recognized as Ibn Khaldūn’s “thoughts on philosophy of history, historiography and sociology” (Ahmad 2017, p. 58). It is obvious that aṣabiyyah is deeply embedded within Khaldūn’s philosophy, and the philosophy of history is deeply embedded in Khaldūn’s conception of civilization. Therefore, for Khaldūn, aṣabiyyah is central to civilization itself.

These three Islamic historians were not only testaments of their time and their environment, but in some cases, acheived a much broader impact outside of the Islamic world in the times that they were alive. Ibn Khaldūn in particular was well-regarded by European as well as Arabic scholars in the 19th century, over 400 years after his death. The historical significance of these historians’ works lie not only in their frameworks, but also in the ways that they were written. Al-Ṭabarī’s manipulation of his sources to fit the particular narrative he wanted to tell was not a new thing with him. It is a seemingly never-ceasing phenomenon within the history of writing history. What these historians did to revolutionize the writing of Islamic history, was the utilization of a thematic narrative. This was seen much later in Europe in the development of the Annales schools and reveals how a “complete” history was understood to be written. This is the brilliance of their contributions to Middle Eastern history. Beyond Al-Ṭabarī’s contributions of narrative in historical writing, and the rationality behind ibn Khaldūn’s understanding of history, the frameworks for history created by these three historians remain an example, as well as a reminder (tazkirah) to consider all potential outliers of history. You may learn something new.

Works Cited

Ahmad, Z. (2017). A 14th Century Critique of Greek Philosophy: The Case of Ibn Khaldun. Journal of Historical Sociology, 30(1), 57–66.

Çaksu, A. (2017). Ibn Khaldun and Philosophy: Causality in History. Journal of Historical Sociology, 30(1), 27–42.

Dale, S. F. (2006). Ibn Khaldun: The Last Greek and the First Annaliste Historian. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38(3), 431-451.

Gabrieli, F. (1979). Arabic Historiography. Islamic Studies, 18(2), 81–95.

Gibb, H. A. R. (1935). Notes on the Arabic Materials for the History of the Early Crusades. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, 7.

Hillenbrand, C. (2008). Reviewed Work(s): The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athīr for the Crusading Period from “Al-Kāmil fiʾl-taʾrīkh,” Part 1: The Years 491-541/1097-1146: The Coming of the Franks and the Muslim Response by Ibn al-Athīr and D. S. Richards. Speculum, 83(3), 712–713.

Judd, S. C. (2005). Narratives And Character Development: Al-Tabarì And Al-Balàdhurì On Late Umayyad History (p. 18).

Kamaruzaman, A. F., Jamaludin, N., & Faathin Mohd Fadzil, A. (2015). Ibn Al-Athir’s Philosophy of History in Al-Kamil Fi Al-Tarikh. Asian Social Science, 11(23).

Keshk, K. (2009). How to Frame History, 381–399.

Mårtensson, U. (2005). Discourse and Historical Analysis: The Case of al-Ṭabarī’s History of the Messengers and the Kings. Journal of Islamic Studies, 16(3), 287–331.

Osman, G. (2001). Oral vs. Written Transmission: The Case of Ṭabarī and Ibn Saʿd, 66–80.

Popkin, J. (2016). From Herodotus to H-Net, 36.

White, A. (2009). Islamic Approach to Studying History, 17(2), 25.