History Under the Third Reich

By MICHAEL MENDOZA

For scholars and students of the history of the Third Reich, a striking aspect of the period remains the degree of compliance and even complicity exhibited by the German people as a whole. Intellectuals were not exempt in this regard. Far from simply being swept-away by events beyond their control, they and historians in particular held great power in shaping the cultural milieu of the Weimar era (c. 1918-1933). As makers and “custodians of the national memory,” historians were essential in building post-WWI national consciousness (Sims, 248-249). The conservative, anti-republican atmosphere they helped foster ultimately proved to be amenable to takeover by far-right authoritarianism. Though many historians managed to keep themselves aloof of the new regime’s agenda, they did so at a cost, and the discipline did not escape the Nazi phenomenon unscathed.

Weimar Historiography

German universities were world-renowned and long considered some of the best as pillars of serious scholarship and free association. German professors were held in great esteem by the public and could easily enter decision-making roles in German society if they wished (247). In a 1951 survey, for example, the most prestigious profession was chosen by Germans as that of the university professor (Dahrendorf, 81). In light of this commanding prestige, German professors were in prime position to encourage opposition to the Nazi movement and later to the regime, particularly historians as the foremost scholars of the relationship between power and the state (Sims, 247).

But the reaction of historians to the crumbling of German democracy and the establishment of a one-party dictatorship was rather muted. Although not a single professor of history was a member of the Nazi party before 1933 (Lambert, 555), none left voluntarily after the takeover and there were only very limited dismissals by Nazi officials, mostly of Jewish professors (Schulze, 25, 28). There was no need for a widespread “purge.” Only a handful of historians deviated from a conservative consensus that in the end proved amply compatible with the fiercely nationalist, virulently anti-Semitic National Socialist (Nationalsozialismus or “Nazi”) movement.

“The historical discipline does not come empty-handed to the new German state and its youth.” (Schulze, 27)

—Karl Alexander von Müller (c. 1882-1964, German historian), 1936

A Bitter Defeat

The year was 1918 when the fronts collapsed and the First World War came to an end. From the ashes arose a new Germany, torn from the imperial power it had possessed at the height of its power not four years before. Germany emerged in a much-reduced state following the territorial and monetary concessions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Vast swathes of German land were given to France and a new Polish state, among other concessions, the armed forces were forcibly disarmed, had their size and equipment restricted, and a vast indemnity was imposed. For much of the German people, if not the vast majority of them, this treaty was a humiliation of the first degree (Evans, “The Coming” 60).

It is no surprise, then, that the newly-constituted, democratic Weimar Republic became the target of conservative and nationalist resentments, being itself the offspring of defeat and the years of chaos and sociopolitical revolution that followed. Historians were no stranger to these sentiments, most shared them and hated the Republic for what it represented: a defeated Germany and democracy imposed by a foreign hand. Even liberals were said to be “republicans of the head and not of the heart” (Schulze, 21). Historians wrote of the “hereditary enemy” of France and created a corpus of so-called “border research” that aimed revanchist sentiments at France and Poland (Schleier, 180). Many historical works of the period attempted to “revise” the Treaty, criticised democracy and the Weimar constitution, and in general demanded a revival of nationalist consciousness that would reawaken Germany from despondency (Schulze, 21). Conservative-nationalist orthodoxy had by 1920 given way to a “vitalist philosophy” which decried a crisis of culture, of politics, and of society. Academics of all stripes latched on to the vague but alluring and potently nationalist ideas of the “state-empire” and the “racial people” (Ayçoberry, 20).

Conservative-Nationalist “Objectivity”

All of this appears to be in contradiction of the values of the self-professed “objective” German historian, the vast majority of whom were steeped in late-nineteenth century positivist thought (which stressed the value of empiricism) and greatly influenced by two German intellectual titans: the sociologist Max Weber (c. 1864-1920) and the historian Leopold von Ranke (c. 1795-1886). Both promoted impartiality, warning against the imposition of contemporary values on times past, as well as objectivity in historical scholarship, urging the limitation of historical concern to a “strict presentation of the facts” (Cheng, 75). What this meant in practice was somewhat vague. Weber stated publicly in 1918 that “politics is out of place in the lecture room” (Sims, 250). And yet, Weber had clearly expressed his own nationalist leanings before, for example at his inaugural address at Freiberg in 1895, by characterizing the unification of Germany in 1871 as a “youthful prank,” urging the young nation to continue forward after what seemed like a pause in national progress (Evans, “The Coming” 39).

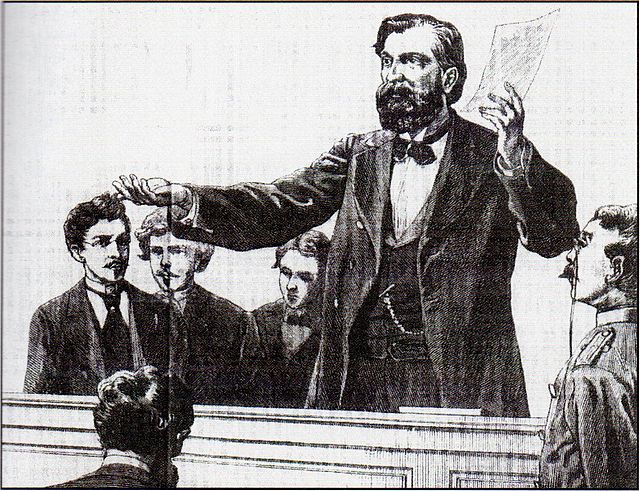

of mid-March 1920. The political street violence, numerous uprisings, and putsch attempts that characterized the Weimar period led many to long for more stable governance.](

/metahistory/essays/images/mmendoza-berlin-defending-natl-assembly.jpg

)

For German historians of the interwar years, conservative-nationalist proclivities lined up conspicuously well with notions of “objectivity.” It was self-evident that the Weimar Republic represented a clear break with German history. Democracy, republicanism, and liberalism were not compatible with the German sense of volk and country, as was “proved” by the social unrest and political chaos that followed the collapse of the Wilhelmine Reich. The German state had been rocked by revolution before, most notably in 1848, but had never emerged a democratized state like other western European nations. Volumes were written on what was seen as a supremely unnatural imposition of democracy on Germany. “The Kaiser-less time,” was widely considered “the terrible time,” in the words of historian Conrad Bornhak (Sims, 253).

Objectivity Versus Impartiality

Why, then, the discrepancy between this apparent bias in historical scholarship and ideals of objectivity and impartiality that historians supposedly valued? It was the result of an intellectual sleight of hand. Through a systematic process of what German historians called ‘Quellenkritik’ (source criticism), the perspectives and context of sources were identified and evaluated. This process lent an air of rigor to the endeavor of the historian. Regardless of the ends to which the history was ultimately applied, political or otherwise, it was believed that the methodological rigor of the process made the work fundamentally “objective” (Daston, 32).

Historians adopted an outwardly apolitical affectation that aligned well with conservative tendencies to avoid supporting narratives that challenged traditional social hierarchies or power structures. The Rankean tradition of suppressing moral and ethical judgements thus promoted scholarship that upheld conservative-nationalist conceptions of German history (Cheng, 75). The few who did write about non-traditional subjects (minorities, women, the working class, etc.) were, in the perspective of conservative historians, being very much biased in their work. Yet simultaneously, some conservative historians were explicitly rejecting Rankean traditionalism by using supposedly “objective” conservative-nationalist narratives to promote their own brand of politics.

Impartiality was even mocked by some like Heinrich von Treitschke as “eunuchry” for the “refusal to put history at the service of life” (Daston, 33). Another Heinrich, von Sybel, who had himself studied under Ranke and went on to found the Historische Zeitschrift (a leading German historical journal) rejected Ranke’s impartiality entirely, calling it “cold” and “colorless.” Georg Gervinus acclaimed the political engagement of historians like Machiavelli for “taking hold of life with both hands” and dismissed impartiality as “political impotence” (31). While affirming the fundamental “objectivity” of their discipline, there was a growing rejection of the idea that historical work should strive to be impartial. Utilizing history in the service of present, political realities was an idea that would only grow further in the coming years.

Völkische History

It was in this intellectual climate post-1918 that the late-nineteenth century notion of ‘Volk’ (an objective grouping of people with a shared ethnicity, language and culture) became increasingly more influential (Schleier, 180). ‘Volksgeschichte’ (people’s or ethnic history) was created by the combination of racial theories with ‘Volkstum’ (people’s character), ideas connected to traditions and culture. This “holistic folk history” became so influential as to rival the traditional grounding of the state as the preeminent object of historical analysis (Schulze, 22).

A new methodology was required to explore this emerging historical paradigm. Methods were adopted from ethnography, settlement studies, as well as linguistics, and more detailed analysis was made of local customs, social, and economic histories (22). All this was contemporaneous to the professionalization of history as a discipline, which more often required extensive technical training. Indeed, the historian Gustav Droysen proclaimed that history should be raised to the “rank of a science” (Iggers, 19), though he rejected the positivist search for deterministic historical laws (Daston, 32). There were attempts to formulate a “new science of history” along Völkisch lines, with those like Erich Keyser urging his colleagues to be more politically explicit and teach “incessantly and in all situations to the political demands of the Volk” (Schulze, 22-23). German historians of the Weimar years thus combined a more empirical methodology with revisionist and nationalist political ends (22), a trend that expanded from 1918 onward and especially after 1933 under the auspices of the Nazi state (Schleier, 181).

“Nothing is more characteristic than to note that neither the bourgeois literature nor the socialist literature has said anything about this party, which ranks second in German politics. It is a party without a history, which has suddenly risen up in the political life of Germany, like an island that emerges in the middle of an ocean through the effect of volcanic forces.” (Ayçoberry, 3)

—Karl Radek (c. 1885-1939, Polish marxist and social democrat), 1930

Historiography Under the Nazis

Through the death throes of the Weimar Republic, as the Nazis gained steadily in the polls and political violence escalated on the streets, German historians became gradually more uneasy. But Rankean ideals alongside a general contempt for democracy subdued most as the Republic collapsed. Few spoke out against the Nazis, notably the historians Gerhard Ritter and Friedrich Meinecke, both of whom broke their silence to urge people to vote for Hindenburg over Hitler. A widely-publicized and internationally infamous motion of support for the new Chancellor made the rounds at German universities and eventually garnered 960 signatures, though over 80% of lecturers had declined to sign (Ayçoberry, 21). Hans Rothfels, himself dismissed from a chair at Königsberg by the Nazis in 1934, condemned as “deeply shameful” what he called the “voluntary coordination” of silence among professors (Sims, 250-251).

The few genuine protestations were hardly the flames of fierce resistance. Meinecke once wrote in a newspaper article that “there are many worthwhile ideas, strengths, and men in this movement” (252). Underappreciation of the anti-intellectual threat of Nazism characterized the early attitude of historians. In fact, Hitler promised much of what most wanted: a revitalized Reich under strong, autocratic leadership.

And so, as the new regime began the ‘Gleichschaltung’ (coordination) of the universities and 15% of the teaching staff in Germany was dismissed following a new law promulgated on April 7, 1933, there was no public, collective opposition on the part of historians nor academics in general (253-254). Outwardly, historians were effectively cowed, either by threat of joblessness or by some measure of approval of the Third Reich. At the International Historical Congress in Warsaw in 1933, the Danish historian Aage Friis expressed his concern that German historians were “compliant and weak” in response to the Nazi takeover (Schulze, 28). The conquest of the German historians’ body complete, the Nazis moved on to conquer the mind. This turned out to be a far more formidable task.

The “Nazi School” of History

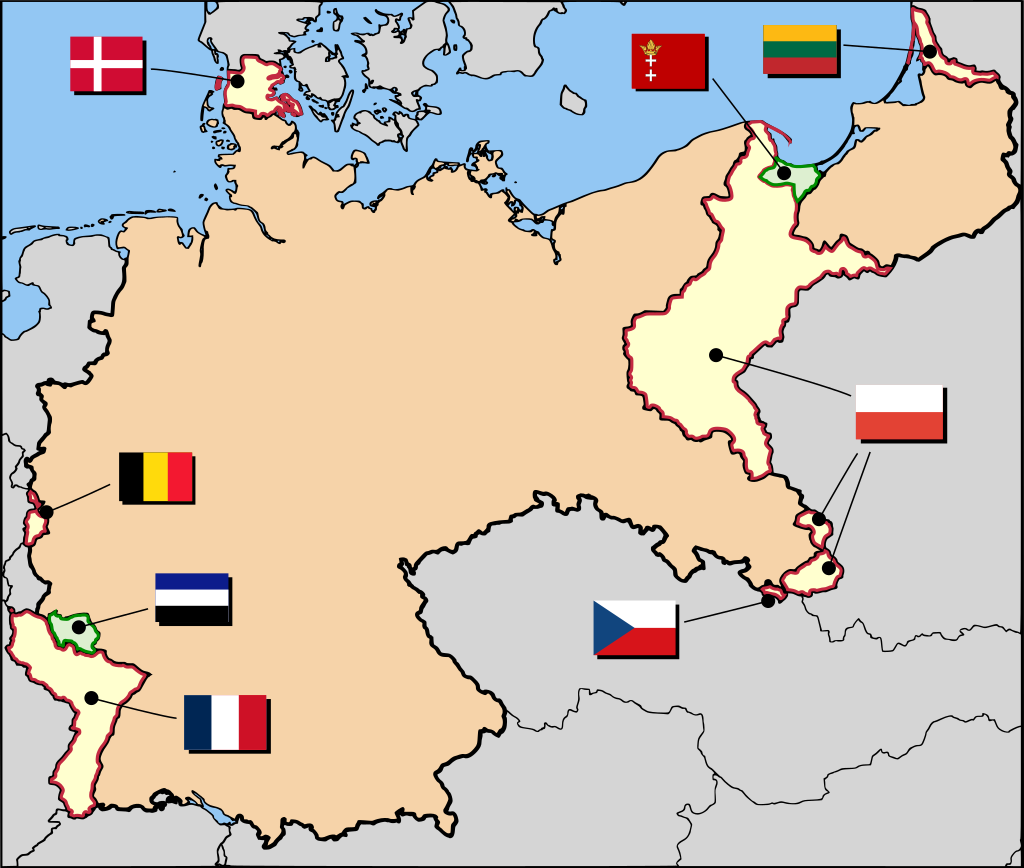

. (Schönwälder, 137-138)](

/metahistory/essays/images/mmendoza-mitteleuropa.jpg

)

For the Nazi program of radical mass political indoctrination to suceed it needed a commanding influence in the schools, and history education was to be at the forefront of this effort, as in fact directed by the Reich Minister of the Interior on May 9, 1933. Another decree later in the same year established new “Guidelines for History Textbooks” that emphasized race as the driving factor underlying history and focused on leadership and heroism in the struggle between peoples and nations (Evans, “In Power” 263).

In the Nazi ‘Weltanschauung’ (worldview), history was conceived of as a Manichean struggle between mutually antagonistic racial forces of the natural versus the parasitic (invariably equated especially with the Jewish people), an almost impossible struggle that could only be won through the contributions of heroic deeds (Ayçoberry, 5). Everything was subordinated to the service of the German Volk in this struggle, including history itself, which was wielded as a cudgel to mold a new generation of young Germans in the National Socialist image. The notion that history should have any pretenses of impartiality at all were jettisoned as a “liberal fallacy” (Evans, “In Power” 263). Curriculums were slimmed to exclude “pointless detail” and focused instead on promoting nationalism (273).

“Obliterate the Traces”

Historians who wholeheartedly embraced Nazism simply discarded the past. Nations had no real progression in history, as “they are already there, prefigured” and could only degenerate (Ayçoberry, 6). Thus, Charlemagne was considered unequivocally German, having “created the Empire” a thousand years before the unification of 1871 (Evans, “In Power” 312). The Germanic migrations were supposedly proof of German racial superiority (Ayçoberry, 7). According to Moritz Edelmann in 1937, editor of a historical journal, historical investigation should “liberate itself from the dependence on the written source” (Schulze, 26).

Medieval history was especially distorted to these ends, an idealized pre-Christian “empire” of Charlemagne virtuous only as a foreshadowing of the new Reich, the Teutonic knights revered as a model of German expansion to the east. As the philosopher and sociologist Max Horkheimer explained, “fascism, by its very exaltation of the past, is antihistorical. The Nazis’ references to history mean only that the powerful must rule and that there is no emancipation from the eternal laws which guide humanity. When they say history, they mean its very opposite: mythology” (Ayçoberry, 7).

(c. 1902-2003) films olympic scenes in Berlin during the 1936 Summer Olympics. This footage would later become the film _Olympia_. Riefenstahl pioneered the art of film propaganda, heavily utilizing symbolism and novel filmmaking techniques like tracking shots, which can be seen here. The eclectic and crude psuedotheories of the Nazis proved amply compatible with the style of Riefenstahl.](

/metahistory/essays/images/mmendoza-leni.jpg

)

The mythologizing of history was not restricted to academic circles. Historical films were especially prized by the Nazis as a means of communicating National Socialist ideals to a mass audience by relying heavily on symbolism. Screenwriters were directed to focus on “the progress of the Nordic man in history. The end of Antiquity, starting point of the alien mind… priests and kings in a struggle for world hegemony… the elements of degenerescence… (liberalism, capitalism, Marxism, confessionalism)…” (Ayçoberry, 10).

The film The Eternal Forest (1936) extolled the soil as the source of Germanic values, depicting the forests of Germany as having endured hardship through war and industrial deforestation but also “humiliated by the occupation of Negro soldiers” just as the German people had been, a reference to the Occupation of the Rhineland by French colonial soldiers between 1918 and 1930 (11). The idealization and romanticism of pastoralism (“soil”) juxtaposed with militant struggle and industrial warfare (“blood”) reveals one of the many contradictions inherent to the Nazi Weltanschauung. Though the source of Germanic values was supposedly the soil and the peasant, the heroes of National Socialism would come from the cities, bedecked in an intensely materialist, racist ideology (8-9).

Tacit Resistance

In spite of mounting pressure from various Nazified organizations to incorporate Volksgeschichte into all forms of historical scholarship, no unified “Nazi Historiography” ever emerged. As in other aspects of the Third Reich, Hitler preferred to leave the jurisdictions of subordinate organizations intentionally vague, promoting infighting that prevented any one agent from gaining too much power; as such the term “Nazi School” is misleading. There were many voices of authority on such matters, among them the Education Ministry, the “Institute of New Germany,” Alfred Rosenberg (c. 1893-1946, a leading Nazi ideologist executed after the war at the Nuremberg Trials for war crimes), and the “Ancestral Heritage Foundation” (Ahnenerbe) of the SS under Himmler (6). Understandings of history from a Volk-centered approach proliferated, but never completely overtook state-centered approaches (Schönwälder, 148). The methodologies of professional historians proved if not outright resistant then at least inertial to the efforts of ideologues to assimilate complex and sophisticated scholarship into crudely-defined Nazi concepts (Evans, “In Power” 312).

Historians resistant to Nazism who chose not to emigrate often dealt with the onslaught through an outward demeanor of conformity to the new regime—an “unpolitical” affectation that was familiar to historians of the Rankean tradition. One educator modified the Nazi greeting to his students in thinly-veiled sarcasm as “Hail, you Ancient Germanic Tribesmen!” (Evans, “In Power” 266). Historians more often avoided controversial subjects and preferred instead to focus their energies on eras far removed from present politics (Schulze, 27). Prominent examples of this “inner emigration” included that of Friedrich Meinecke’s The Rise of Historicism and Gerhard Ritter’s books on Martin Luther and Frederick the Great, two figures exalted by the Nazis—though Ritter in defiance formulated these works as repudiations of Nazi ideology (Sims, 257).

As noted by the SS Security Service in 1938, the vast majority of historians continued their research unabated by political events, carrying on “compiling old scholarly encyclopedias” and delivering “new scholarly contributions to the illumination of individual epochs” (Evans, “In Power” 313). Some historians found that they could get away with subtle criticism of the regime by couching it in historical comparison, such as Hermann Oncken, who wrote critically of revolutionary leaders like Robespierre and Oliver Cromwell in his books and articles in such a way that mirrored the actions of Adolf Hitler. Informers and local Nazi Gauleiters (regional leaders) often lacked the intellectual sophistication required to see these forms of resistance for what they were (Sims, 258).

On the whole, therefore, efforts to Nazify history were largely unsuccessful within the academic sphere; Nazi psuedotheories simply did not hold up to the methodological and theoretical rigor of professional historians. The Historische Zeitschrift, which had published articles on the “Jewish Question” (among others), continued to publish conventional articles untainted by Nazism. When the premier national, annual historical conference became dominated by committed Nazis, most historians simply did not attend any longer (Evans, “In Power” 313). Even those initially pleased with the new regime eventually became involved in conflict with local Nazi appointees or zealous student organizations. It is not always so clear where compliance ended and dissent began. However, seen from outside of Germany, historical scholarship was nonetheless severely curtailed in areas that criticized far-right conceptions of history (Schulze, 29).

“No one has repudiated German history more than the Nazi ideologists.” (Ayçoberry,7)

—Karl Ferdinand Werner (c. 1924-2008, German historian)

Post-War Nazi Influences

The cataclysmic end of the war for Germany resulted in a crisis of historical scholarship. There were widespread calls to reexamine conventional historical theses. In this respect, 1945 really did seem like a complete break with the past, “the end of traditional history” (Schulze, 31). What did “German history” mean in an era without a German state? West German historians insisted that modern scholarship could continue as “true” history released from the trappings of Nazi rhetoric, as it was claimed that many had simply paid lip-service to Nazi ideology to retain their jobs. But the extent to which Nazi-era historiography affected post-war methodologies was indeed in question.

Undoubtedly, paradigm shifts initiated during the Nazi era found some forms of continuity with post-war scholarship. Volksgeschichte in particular retained a powerful influence on the social sciences post-war (Schönwälder, 142-143). No longer were historical shifts primarily conceptualized as arising from politics and the state, but rather from society—a tradition firmly rooted in Völkisch analysis, drawing a clear connection between paradigms of the 1930s and the 1960s (Schulze, 20).

There was a widespread post-war consensus among both historians and the general public that a thorough revision of German history was needed, the search for the “junction” where German history “began to err from its path” (30). But this waned as the new West German Federal Republic gained solid political standing, the majority of historians preferring to return to “normalcy” and continuity in scholarship. Though a degree of “traditional” historical debate did return, retreading familiar ground like that of the Bismark era, it was clear that the post-war historical paradigm had been irrevocably altered. Focus on Volksgeschichte during the National Socialist era had, for better or worse, brought about the “social revolution” that had been so delayed in Germany by the failure of the revolutions of 1848 and 1918, at least in thought if not in political reality (38).

It was from this tug-of-war between traditionalist historians and the younger generations over what history had been tainted by the Nazis and should be jettisoned that the beginnings of a decades-long debate emerged over the extent to which the German culture and people were culpable for Nazism, eventually morphing into the Historikerstreit (“historians’ dispute”) of the 1980s. That debate continues to smolder in certain respects even today, as German historians struggle to come to terms with their profession’s complicity in the origins and silence in the face of genocidal actions committed by the Nazi regime in those darkest years of German history.

Bibliography

Ayçoberry, Pierre. The Nazi Question : An Essay on the Interpretations of National Socialism (1922-1975). Pantheon Books, 1981.

Cheng, Eileen K. Historiography: An Introductory Guide. Continuum, 2012.

Dahrendorf, Ralf. Society and democracy in Germany. Norton, 1979.

Daston, Lorraine. “Objectivity and Impartiality: Epistemic Virtues in the Humanities.” In The Making of the Humanities: Volume III: The Modern Humanities, edited by Rens Bod, Jaap Maat, and Thijs Weststeijn. Amsterdam University Press, 2014. 27-42.

Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. The Penguin Press, 2004.

Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich In Power. The Penguin Press, 2005.

Iggers, Georg G. “Nationalism and historiography, 1789-1996: The German example in historical perspective.” In Writing National Histories: Western Europe Since 1800, edited by Stefan Berger, Mark Donovan, and Kevin Passmore. Taylor & Francis Group, 1999. 15-29.

Lambert, Peter. “German historians and Nazi ideology: the parameters of the Volksgemeinschaft and the problem of historical legitimation, 1930-45.” European History Quarterly 25, no. 4, 1995.

Schleier, Hans. “German Historiography under National Socialism: Dreams of a powerful nation-state and German Volkstum come true.” In Writing National Histories: Western Europe Since 1800, edited by Stefan Berger, Mark Donovan, and Kevin Passmore. Taylor & Francis Group, 1999. 176-188.

Schönwälder, Karen. “The Fascination of Power: Historical Scholarship in Nazi Germany.” *History Workshop Journal 43, no. 1 (March 1, 1997): 133–53.

Schulze, Winfried. “German Historiography from the 1930s to the 1950s.” In Paths of Continuity, edited by Hartmut Lehmann and James Van Horn Melton, 1st ed., 19–48. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Sims, Amy R. “Intellectuals in Crisis: Historians Under Hitler.” The Virginia Quarterly Review 54, no. 2, 1978: 246–62.

Images

Heinrich von Treitschke im Hörsaal.

german_losses_after_WWI. CC BY-SA 2.5

Franz Eichhorst 1885-1948 war painter Rathaus Berlin-Schöneberg Bürgersaal fresco 1935–38 Nazi propaganda “Bauer” Galleria. CC BY-SA 4.0

Berlin defending Nat’l Assembly.

“Propaganda Shirley” by Kim P. Flickr, 2005. CC BY-SA 2.0. (This contemporary photograph is not Nazi propaganda but affects the same symbolism: extolling the virtues of the European peasant farmer.)

Riefenstahl filming a difficult scene with the help of two assistants, 1936. CC BY-SA 3.0

Hitler Youth at rifle practice, c. 1943. Bottom of the image cropped. CC BY-SA 3.0