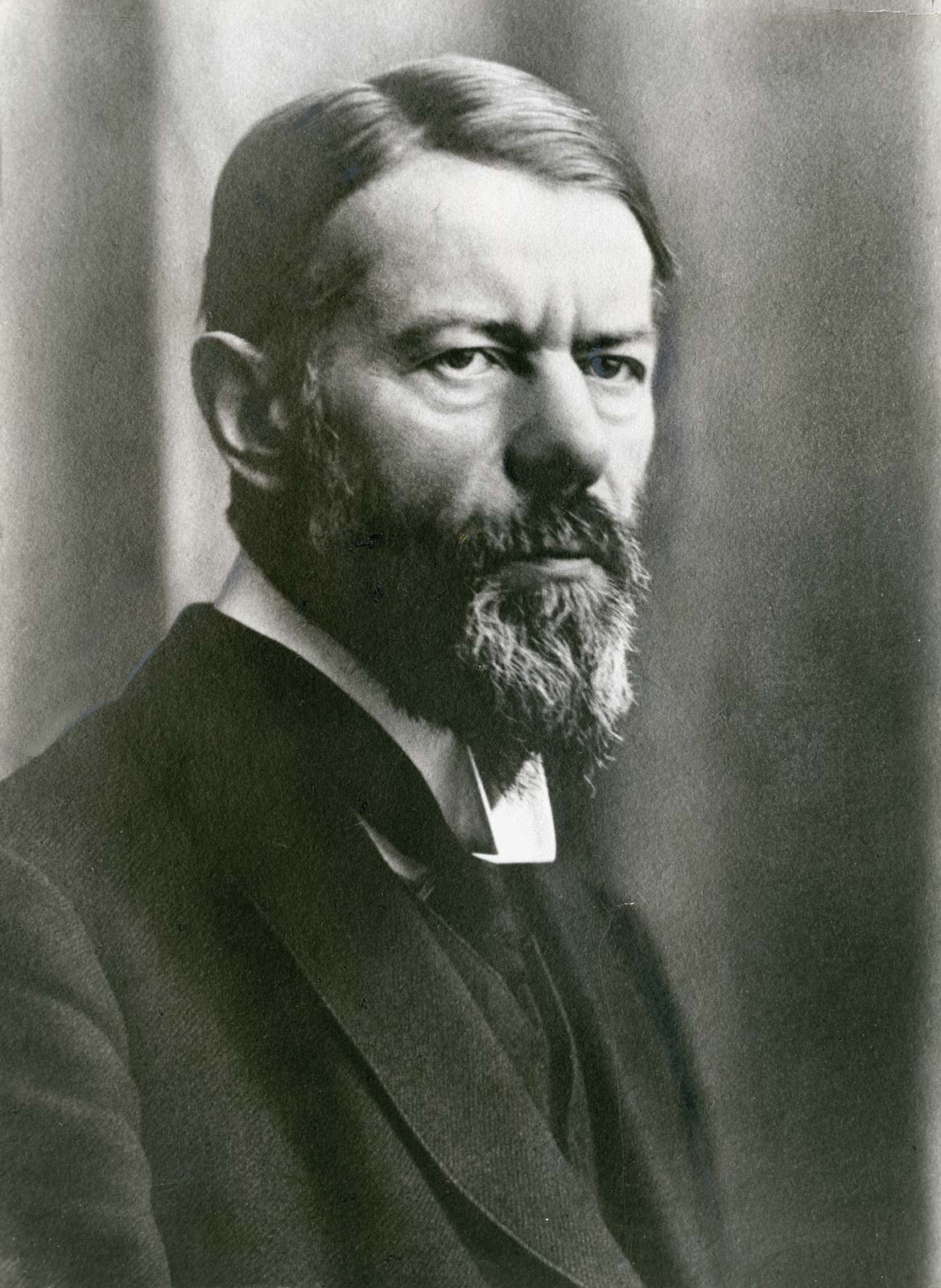

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber

The Iron Cage, Ideal Types, and Social Actions

By Sadie Baca

Recognized as one of the fathers of sociology, mid-nineteenth century German historian, economist, philosopher, and lawyer Max Weber (1864-1920) profoundly changed historical causation and research with his delimited narratives. Weber’s biggest contribution to historical writing was his historical analysis of religious and cultural connections to the rise of capitalism, authority, and social actions.

The historical school of thought at the time, Marxism and modernization, oversimplified and dismissed cultural and religious influence on driving the development of social action and economic structures. Weber “focused on the cultures we create rather than dismissing structural and other issues’’ (Giddens, 1970, 289–310). Weber sought to validate the relevance of both religion and culture by demonstrating how these institutions are responsible for the creating and maintaining capitalistic systems that dismiss their usefulness when explaining historical events. Weber changed historical analysis of his time due to his ability to understand that religion and cultural ideals cannot be scientifically reduced; they have importance and meaning in historical events that we use to explain human nature and the driving forces of how the structures around us came into existence. Weber saw that reducing historical events to just materialism and social structures, as Marxist and modernist did at the time, limited, devalued, and discounted the importance and impact of culture and religion on the development of economic structures.

His most known works, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904) and the Economy and Society (1922), published after his death, shaped new ideas about how influences are ingrained in religion and cultures and can be attributed directly to the origins of capitalism and materialism in the modern era. To describe the aspects of modernity and the rise of captialism, Weber focuses on understanding the origins and effects of rationalization, secularization, and disenchantment.

INTERPRETATIONS OF THE CONDUCT OF HISTORY

Max Weber (1864-1920) a German native, was the oldest of seven children, and grew up during the Western modernization and industrialization period. Weber was born to a French absolutist and devout Calvinist mother, who strongly believed in God’s preordained plan and attributed material and monetary success to the grace of God. His father was a wealthy German dedicated civil servant, social scientist, and a member of the National Liberal Party, who supported nationalism and liberalism. Having two diverse and intelligent parents, Weber was well versed in politics, sociology, law, religion, and economics. He was highly educated, and had strong morals and values. At eighteen, Weber attended three top German universities, Heidelberg, Göttingen, and Berlin, where he gained three PhDs simultaneously in economy, history, and philosophy, concurrently while he gained his J.D. in law in a short time. Weber himself was extraordinarily brilliant and driven.

.jpg

)

At the time, “across Europe, the nationalization of history took place as part of national revivals in the 19th century, where historians emphasize the cultural, linguistic, religious and ethnic roots of the nation, leading to a strong support for their own government on the part of many ethnic groups, especially the Germans” (Historiography of Germany). This advent, of the nationalization of history and the Industrial Revolution, brought forth what Snyder says “marked a point in society where humans moved away from religious traditional worldviews of history and towards modernity, a more scientific explanation and more rationalized history which caused the evolution of bureaucracy and urbanized state with an accelerated world financial exchange and communication” (Snyder). This is because during the modernization of the Western world, there was a social movement towards more scientific and rational interpretations of nature and human behavior to explain historical events and phenomena called rationalization. Secularization is the movement away from religion and supernatural phenomena as explanations of the world and human behavior. In Weber’s opinion the rationalization and secularization of modern Western societies caused disenchantment, which is the end result of devaluing religion and culture, breaking down social bonds and leading to the rise of capitalism.

Weber’s revolutionary ideas came from him delimiting the known concepts of his time. The modern era’s Marxist ideas of social structures and materialism limited and undervalued peoples cultural and religious beliefs and dismissed their impact and importance on these structures.Weber’s historical analysis opened the narrative of how culture and religion are important to explaining historical causation, and has contributed to the rise of capitalism and values that maintain the system of bureaucracy. Unlike Karl Marx and other German contemporary historians of his time, who attributed to economic materialism to historical causation, “Weber sought to combine the systematic pursuit of valid historical generalizations with an emphasis on the need for an interpretative understanding of the internal meanings of human behavior, both in the sense of individual motives for action and in the wider sense of collective belief systems which could not be reduced to some underlying material base” (Fulbrook, 15). To do this Weber begins to establish connections between religious ethics and bureaucracy, “debating the significance of the puritan movement or more generally the problem of the relationship between religion and politics” (Burke, 110).

THE PROTESTANT ETHIC AND THE SPIRIT OF CAPITALISM

Weber’s most seminal work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), main goal is to gain an understanding of what gave rise to the spirit of capitalism in the modern world. To do this Weber surveyed the relationship between the development of the spirit of capitalism and the strong work ethics of strict Protestantism, and Calvinist preordained virtues in work and profit. Weber describes the spirit of capitalism as bureaucratic ideologies that promote and preserve the rational pursuit of material gains. According to Weber, as society modernized, economic activity locked people into the ‘spirit of capitalism’. Weber concluded that without religion, the spirit of capitalism would not exist. Thus, the Protestant ethics helped drive the restructuring of the traditional economic life in order to create a calculated rational system. The calculated system of capitalism drives rationalization and secularization to the point that religious and cultural views, which encouraged and produced the evolution of this system, deteriorate and are undermined, ignoring their true significance and impact on historical events.

THE IRON CAGE

According to Weber, once society is locked into the spirit of capitalism, and after enough time has gone by to where society no longer questions the spirit or system, people then become locked in the iron cage, a bureaucratic system of control, materialism, and rational-legal choice. The iron cage is characterized by excess rationality, extreme specialization, and alienation. Excess rationality creates a system that is fully dictated and micro-managed based on scientific methodology. Extreme specialization is when excessive rationality narrows down work tasks to boring, mindless, insignificant jobs which leaves people feeling alienated from their labor that holds no emotion, artistic value, and is passionless. When society fully submits to this system, the processes and methods used in the modern industries’ means of production, materialism, and control escape and begin to influence all aspects of daily lives, thus trapping people in the iron cage. Weber saw that capitalist ethics became so persuasive and reliant on daily lives and as a result of this over rationalized system, limited individual human freedoms and reduced people to mindless task workers.

The iron cage has both positive and negative contributions. “Weber wrote that bureaucracies are goal-oriented organizations that are based on rational principles that are used to efficiently reach their goals” (Hamilton, Peter. Max Weber: Critical Assessments. 1st ed.,1991. 294). This means things get done effectively and efficiently based on rationality. However, “Weber also recognizes that there are constraints within the “iron cage”, such as the fact that the system is often unregulated and a very small group of people concentrate all the power in this system (Ritzer, George. Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption. 2nd ed., 2004. 56). Weber believed that those who control these organizations control the quality of our lives as well and is an “inescapable fate” (Weber, Max, 1978. 1403). The inescapable fate Weber refers to is humanity being locked in a rigid system that strips people of humanity, and limits individual freedoms and choices. In this way, institutions entrap humans into the capitalist machine that dictates every aspect of daily lives.

IDEAL TYPES

According to Weber, once society is locked into the spirit of capitalism, and after enough time has gone by to where society no longer questions the spirit or system, people then become locked in the iron cage, a bureaucratic system of control, materialism, and rational-legal choice. The iron cage is characterized by excess rationality, extreme specialization, and alienation. Excess rationality creates a system that is fully dictated and micro-managed based on scientific methodology. Extreme specialization is when excessive rationality narrows down work tasks to boring, mindless, insignificant jobs which leaves people feeling alienated from their labor that holds no emotion, artistic value, and is passionless. When society fully submits to this system, the processes and methods used in the modern industries’ means of production, materialism, and control escape and begin to influence all aspects of daily lives, thus trapping people in the iron cage. Weber saw that capitalist ethics became so persuasive and reliant on daily lives and as a result of this over rationalized system, limited individual human freedoms and reduced people to mindless task workers.

The iron cage has both positive and negative contributions. “Weber wrote that bureaucracies are goal-oriented organizations that are based on rational principles that are used to efficiently reach their goals” (Hamilton, Peter. Max Weber: Critical Assessments. 1st ed.,1991. 294). This means things get done effectively and efficiently based on rationality. However, “Weber also recognizes that there are constraints within the “iron cage”, such as the fact that the system is often unregulated and a very small group of people concentrate all the power in this system (Ritzer, George. Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption. 2nd ed., 2004. 56). Weber believed that those who control these organizations control the quality of our lives as well and is an “inescapable fate” (Weber, Max, 1978. 1403). The inescapable fate Weber refers to is humanity being locked in a rigid system that strips people of humanity, and limits individual freedoms and choices. In this way, institutions entrap humans into the capitalist machine that dictates every aspect of daily lives.

“In a basic sense charismatic authority represents a pattern of psychological, social, and economic release: a release from ‘traditional or rational everyday economizing, a release from ‘custom, law and tradition’, a release from ‘all notions of sanctity’, a release from ‘ordinary worldly attachments and duties of occupational and family life’, and a release from oneself or one’s conscience” (Weber, ed. 1947, 362 & 1117).

SOCIAL ACTION

Weber’s “proliferation of explicit conceptual categories attempted to develop a social equivalent of the Scientific Table of Elements, which with different mixes, produce different complex phenomena in the real world, thus allowing the scholar to compare reality against the constructed ideal type” (Fulbrook, 89-90). His last book Economy and Society (1922), Weber creates a new historical approach to methods, validity, and scope, and pushes historians to distinguish between justified belief and opinion by using four types of categories, a ‘scientific table of elements’ of social action. Weber’s characterizes the four categorical mixes of social action: goal-rationality or rational-purpose action, value-rationality action, emotional-rationality action, and traditional action). “Each action is based either on technology (emotional-rationality), content (traditional), pedagogy (value-rationality) and market/business (Goal-rationality) as governing” (Duus, 24).

The goal-rational aspect can have multiple means and ends, the value-rational occurs when using rational to effectively achieve goals or a means to an end in subjective terms. Emotional-rationality action is emotional and impulsive due to fusing means, ends, and goals together. While traditional action can occur the means and ends are affected by customs and traditions in that society. “Weber’s analysis of bureaucracy emphasized that modern state institutions are increasingly based on the latter rational-legal authority, while legal rationale is just a system of rule of law, traditional authority through rationalization becomes legal-rational authority” (Duus, 24). By doing so, “Weber was able to legitimize the scientific approach both by recognizing and delimiting the subjective dimension of the cultural significance of historical studies by emphasizing the indispensability of concepts in historical analysis” (Shills & Finch, 17).

To Weber objective values cannot be understood, thus appeal or influence on history will be limited. Through these categories, Weber tries to determine if people engage in purposeful or goal oriented rational action, value-oriented action, engaging with traditional actions or acting through emotional motivations. This is how Weber delimits objective historical values that reject subjective interpretations and explanations of historical events in the modern world. Weber saw subjective values as important driving factors that cannot be dismissed in discovering social actions in historical events. Using transparency in methods and challenging paradigms encouraged greater narratives that construct historical events. Weber’s unique historical narratives and analysis opened and heightened our awareness of social constructs and how they impact historicism. He shows us how we can isolate ideologies that grew from certain legal, goal, purpose, value, emotional, rational, or traditional actions. Weber’s works helped reshape and open new avenues for historical explanations, interpretations, and paradigms.

Bibliography

Burke, Peter Social History 10, no. 1, 1985.

Dow, Thomas E. “An Analysis of Weber’s Work on Charisma.” The British Journal of Sociology 29, no. 1, 92, 1978.

Duus, Henrik Johannsen, E-learning Paradigms and The Development of E-learning Strategy, 2006.

Fulbrook,Mary Historical Theory (1st ed.). 2002.

Giddens, A. Marx, Weber and the Development of Capitalism, 289–310, 1970.

Shils Edward A. & Finch Henry A., The Methodology of the Social Sciences (1903–17), 1997.

Snyder, S. L.”Modernity” Encyclopedia Britannica, May 20, 2016.

Swedberg, Richard & Agevall, Ola,. The Max Weber Dictionary, 2005.

Weber, Max, Economy and Society, 1922 & 1978.

Weber, Max , The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 1905.

Wikipedia contributors, “Historiography of Germany,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2021.