Early Soviet Historiography

The Battle to Fit Ideaology into a Historical Narrative

By ERIC GALBISO

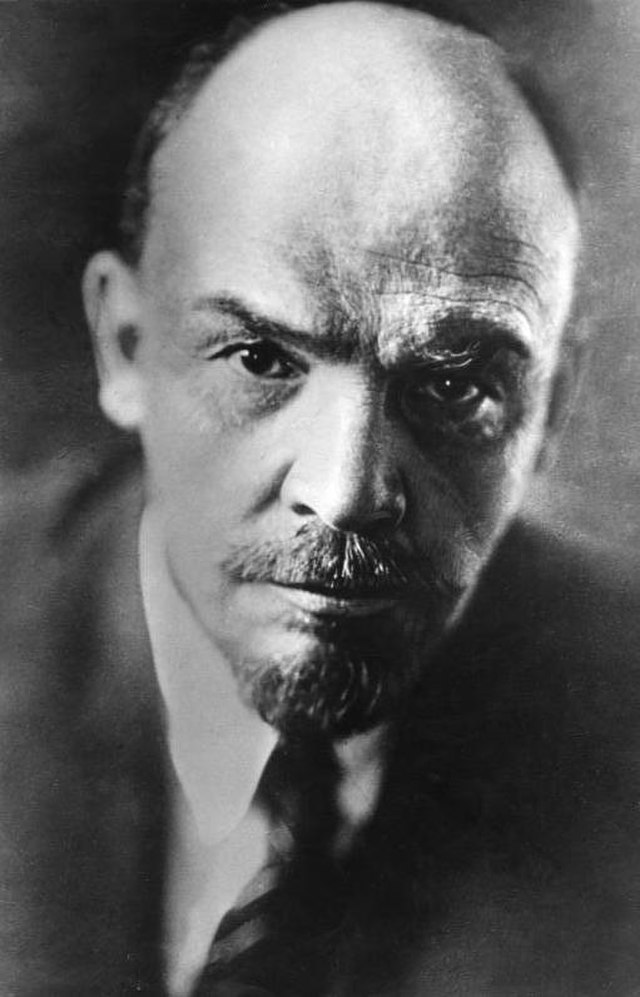

Early Soviet historiography was shaped by various conflicts, the Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, and the Russian Civil War, as well as political controversies of Soviet Party leadership. Starting in the late nineteenth century, Russians began to embrace the ideas of Marxism, which helped create change in society and country leadership. The main figure in this early change was the revolutionary leader, Vladimir Lenin. Lenin was the central character in which all of society, including historiography, would revolve around through his own will and through the will of the Communist Party that he helped found and lead.

A great deal of Soviet historiography has to do with the role of Marxism, specifically the Marxist-Leninist interpretation, throughout history. Many historians adopted Marxist ideologies and tried to fit their views into not only Soviet history, but Russian history as a whole. Soviet historians were tasked by the Communist Party to interpret history as favorable to the rise of the Communist Party and to silence history that could contradict the narrative.

This essay seeks to explore the historiographical struggle in the early era of the Soviet Union from 1917 to Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. This brief overview will examine several historians, including the would-be historians, institutions, ideological struggles, and how the Soviets attempted to justify their actions during the aforementioned conflicts and the power wielded by the resulting government.

Marxists and non-Marxists

The entirety of post revolution Soviet society was supposed to be built on the Marxist ideology, but it was not a simple task to simply get rid non-Marxist’s believers. Educational institutions in the early era of the Soviet Union were examples of this as they found it difficult to push out the non-Marxists from continuing their work. The Soviet Marxists were guided by the principles of Marxism-Leninism. Marxism-Leninism was built on a series of socioeconomic formations that followed an evolutionary process that included primitive communism, slave-holding society, feudalism, capitalism, and communism.

Marxist historians preferred to not work with non-Marxists because they felt that the non-Marxists could still be a threat to the Communist Party through their interpretations of history. The Communist Party allowed the non-Marxists to continue their work, but it heavily monitored. Several competing institutions of both ideologies were created to formulate Soviet history with Marxists taking on the leadership roles.

The Marxist institutions included, the Society of Marxist Historians (part of the Communist Academy), the Commission for the Study of the October Revolution, and the Russian Communist Party (Istpar), and the Institute of Red Professors. All of these institutions had the main mission of promoting Marxist history and were headed by Mikhail Pokrovsky. These institutions were used to collect materials pertaining to party history, have historical discussions, and to keep non-Marxist histories contained.

The non- and semi-Marxist institutions includes the Academy of Sciences in Leningrad, GAIMK (State Academy for the History of Material Culture), and RANION (Russian Association of Social Science Institutes). These state sanctioned institutions were used to allow bourgeois scholarship to continue in a controlled environment where all works could be edited to the Communist Party’s liking.

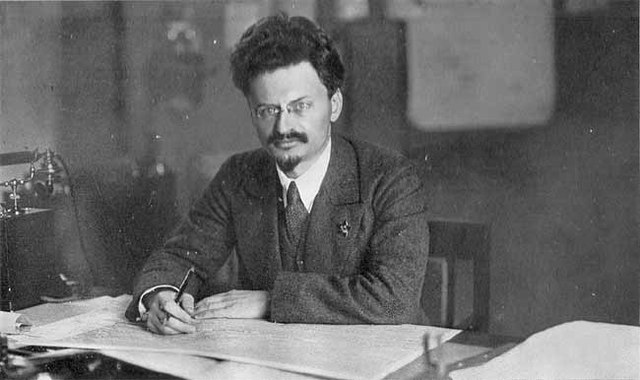

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky was a leading Russian revolutionary and not a trained historian, but he had great contributions to the study of Soviet history. Trotsky’s belief of the Marxist ideology, referred to as Trotskyism, differed from many other revolutionaries in that he believed in a permanent revolution where social change was constant. This difference in ideology would play a part in his eventual downfall because he believed the way the Communist Party interpreted Marxism-Leninism into government actions was out of sync with true Marxism-Leninism. There was no other greater example of this than his main rival, Stalin.

Trotsky’s main focus was on the Revolution of 1917. His first work on the subject was a historical pamphlet, History of the Russian Revolution to Brest-Litovsk, about the October Revolution that sought to justify the actions of the Bolsheviks. Trotsky wanted to show that the Bolsheviks were not usurpers of power and they were successful because their revolution was inevitable, through the lens of Marxism, and they had wide support of the people. This Lenin approved pamphlet became an early official history of the Revolution which defined how all others were to be written.

Even after falling out of favor with the Communist Party and getting deported from the USSR, Trotsky wrote some of his seminal works about the Revolution, including The History of the Russian Revolution and his autobiography My Life. Although My Life is an autobiography, this book was a great tool for Soviet history because it is a firsthand account of many of the revolutionary events that led to the eventual rise of the Soviet Union.

There had been several other works about the Revolution but none that were as extensive as Trotsky’s History. History was the preeminent historical work that took into account the entire Revolution of 1917, from February to October. His underlying purpose was to elevate his position as being the other true leader of the Revolution alongside Lenin and to call out other Soviet leaders, especially Stalin, as being unworthy of leading the Communist Party.

It would be worth reiterating that Trotsky was not a trained historian. He relied on his own memory to formulate his works and the publications of the Istpar. To say that his writings were completely biased due to his sources being Communist Party approved would be an understatement. With that being said, Trotsky’s contributions to this period of Soviet historical writing were enormous.

The Father of Soviet Historiography

Mikhail Pokrovsky was the preeminent Soviet historian who has been widely recognized as the “father of soviet historiography”. (Eissenstat, 604) Pokrovsky was a founder and leader of several of the historical institutions, historical journals, and the training of historians. Pokrovsky believed in the Marxist theory that economics and material needs was the main driver of history and living people had a part to play but it was the collective and not the individual that made history. He used this theory to show that the Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 were living proof that Marxism was the correct ideology because the Bolsheviks were victorious.

Although Pokrovsky had a certain amount of latitude when it came to his work, he still had to fall under the party line as the as the Communist Party gained more control. Like many other historians of the time, he had to cite Lenin in almost every piece of his work to show his loyalty to the Communist Party and that he was a true believer of Marxism. For example, “For any correct interpretation of Russian history must be based on Lenin’s interpretation of it”. (Eissenstat, 610)

It would be surprising to learn that a historian under such a repressive regime that was attempting to rewrite history to fit their narrative would have such strict ethical standards when it came to sources, but Pokrovsky felt it was his duty to the proletariat to make sure documents were not altered because thought the people deserved to know the truth.

While Pokrovsky wielded a great amount of power as essentially the dean of Soviet history, his reputation and works were ignored and condemned after he died in 1932. Many critics accused him of not being a true Marxist and that his style of teaching was running counter to the demands of the Communist Party.

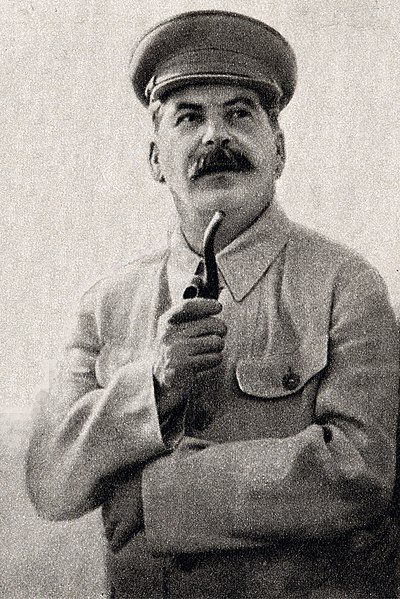

Stalin and the Short Course

In 1931 Joseph Stalin wrote a letter to Proletarskaia Revoliutsiia (Proletarian Revolution) criticizing the way historians had portrayed Lenin and Communist Party history. This letter was the first public admission that Stalin was not happy with the way historiography was performed and it would not be the last time Stalin and party members would intervene in the writing of history.

A main criticism Stalin had was the way previous histories had been written, especially the way they were framed chronologically. Stalin called for a new textbook to be written, under his framework and with the Communist Party’s guidance, that would focus on the history of the Communist Party.

In 1938 the textbook was published, titled History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Short Course. The Short Course was primarily written by historians Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov and Yemelyan Yaroslavsky with an essay being authored by Stalin himself. The authorship would eventually change because Stalin would take credit for writing the entire book himself.

The Short Course was supposed to be a textbook that exemplified the Marxist theory of history by speaking to the collective as drivers of history but ended up elevating individuals, Lenin and Stalin, as the creators of history. The Short Course made Stalin into the hero of the Soviet Union which further solidified his standing with the public.

The Short Course became the basis of all Soviet history and was supposed to be used by all Soviets and non-Soviets alike as a guide to Leninism-Marxism. It was distributed and taught throughout the government and education system. No other histories were allowed to be produced without the consent of the Communist Party.

Conclusion: Stalinist Repudiation and Reflection

Not long after the death of Stalin in 1953 the Short Course fell out of favor with the Communist Party and the Soviet Union overall. When Nikita Khrushchev came into power, he called for new history books to be created and for the Short Course to be removed from educational institutions. Khrushchev’s efforts to de-Stalinize Soviet society helped the profession of history by allowing historians, including non-Russian outsiders, to finally reenter the archives that were shut during Stalin’s reign.

The early era of Soviet historiography was one of tumult, but it is fair to say that Stalin brought about a sense of peace to the profession when he solidified his power. There was less fighting amongst historians but there was too much appeasement towards Stalin and the Communist Party. What would follow would be a more open form of historiography but one not without its own faults.

Bibliography

-

Avrich, Paul H. “The Short Course and Soviet Historiography”. Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 4 (Dec., 1960), pp. 539-553.

-

Banerji, Arup. “Notes on the Histories of History in the Soviet Union”. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 9 (Mar. 4-10, 2006), pp. 826-833

-

Baron, Samuel H. “Plekhanov, Trotsky, and the Development of Soviet Historiography”. Soviet Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Jul., 1974), pp. 380-395

-

Eissenstat, Bernard W. “M. N. Pokrovsky and Soviet Historiography: Some Reconsiderations”. Slavic Review, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1969), pp. 604-618.

-

Enteen, George M. “Marxists versus Non-Marxists: Soviet Historiography in the 1920s”. Slavic Review, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar., 1976), pp. 91-110

-

Mazour, Anatole G. Modern Russian Historiography. Greenwood Press, 1975.

-

White, James D. Leon Trotsky and Soviet Historiography of the Russian Revolution (1918–1931). Routledge, 2021.