Eurocentrism

By Keena Hays

Have you ever read a book with a non-Western protagonist? Have you ever questioned the author’s motivations for writing?

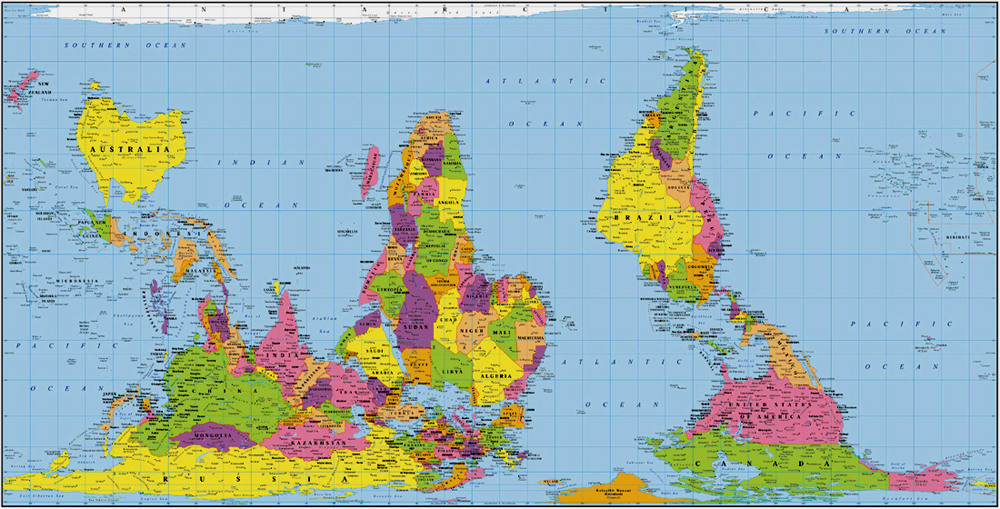

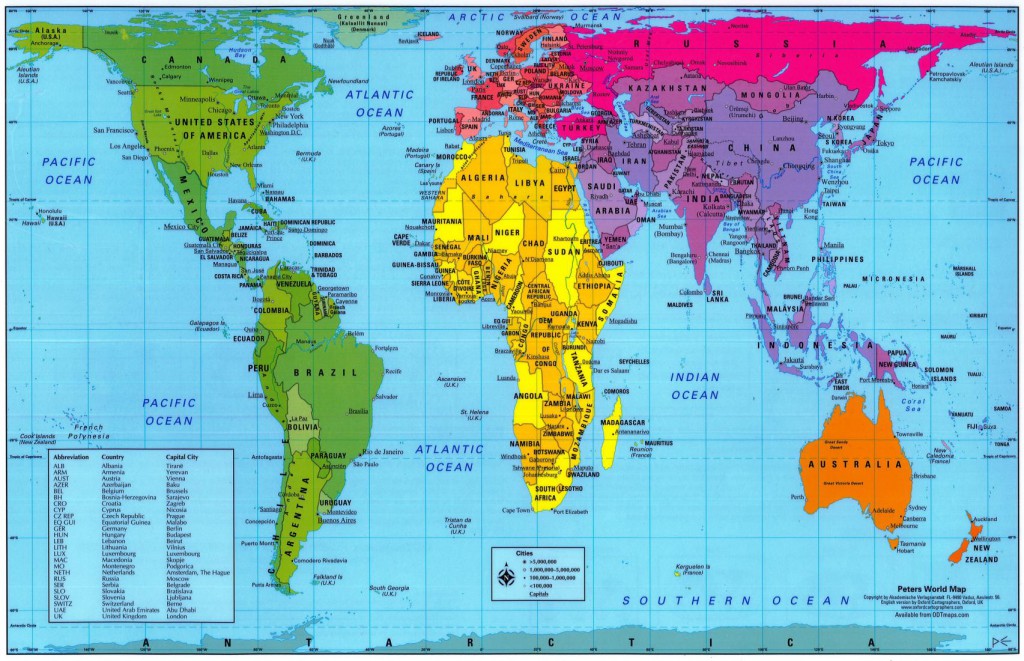

Inherently, the term ‘Eurocentric’ is easy to parse, ‘euro’ is Europe and ‘centric’ is center. Simply, it is that Europe is and has historically been viewed as the center of the world, or the focus (more so than the geographical center). Before encountering the Americas, historians believed Europe was the only ‘west’, naturally designating all other regions as ‘north’, ‘south’, or ‘east’ from that focal point. But, there is much more to Eurocentrism than locality. Europe is also a concept itself. Much like Eurocentrism, Europe is an idea that a group of people collectively came to understand and agree upon. This idea formed into a culture, with certain values and practices which differentiated it from other cultures, until eventually coinciding with a specific image in our heads of what it means to be ‘European’, ‘Western’, or ‘civilized’.

Eurocentrism: What is it?

Why does the word “West” only refer to certain regions of the world? Why do we think of Russia as east of Europe, rather than west of China?

Eurocentrism encompasses many Western concepts and their effects, including colonialism, capitalism, monotheism, racism, and patriarchy. Yet, viewing the world with a Western perspective even impacts less-obvious aspects of daily life, such as conceptions of time, the calendar, familial structures, cosmology, use of the environment, etc. Eurocentrism itself is not individually any of these concepts, but rather the amalgamation of the hegemonic entity of European culture. Through time these concepts influenced the world to such a degree that perspectives skewed to view Europe as “better”, “more civilized”, “more developed”, or as a “First World” in comparison to non-European regions. Eurocentrism acted as both the motivation for and the outcome of many of these listed concepts, giving it its complex, multilayered identity. We will specifically explore Eurocentrism in historiography, or how history has been written with a Eurocentric perspective and the influence of those perspectives.

Origins to Present

Many authors of Eurocentrism trace its origins as far back as ancient Greece, which acted as a continental “crossroads” between Europe, Africa, and Asia, and an origin of textual historical documents. For centuries, historians understood the Mediterranean as the origin of European culture and of humans themselves, civilization, democracy, and philosophy. With a political system based on imperialism, that is, expanding of an empire, and colonialism, the control or occupancy of another region, it is clear that a foundation for Eurocentrism began in Greece. However, Eurocentrism today has a much more complicated interaction with the world which is more closely linked to the late Roman period, around the fifth century.

The More You Know: The term “Barbarian” is actually a Greek term used to describe anyone who did not speak Koine Greek, the common language in ancient Greece. ‘ian’ means “one who speaks” and ‘bar’ describes what Grecians thought non-Greek languages sounded like, “barbarbar”.

In response to the Roman defeat by the Visigoths in 410CE, Bishop Augustine of Hippo wrote a document titled City of God. His intention was to explain the reasons for Roman defeat and attempt to understand human history, as well as predict the future fate of humanity (Fortin, 324). However, as historians, we can examine this document for much more than its intended purpose. In this moment, Augustine redefined history as not only a Western one, but as a Christian one. This belief system became the basis for contemporary Eurocentrism, much more permeating than the Greeks ever employed. With the addition of Christianity to Western, European identity, the concept of paternalism, or Europe viewing itself as a ‘father’ to the rest of the world, soon intertwined with this identity. Already well-developed in the Roman-Catholic church (think of the male-dominated clergy and the Christian god as a man and father), paternalism offered a new understanding of Europeanism that not only provincialized all non-European countries, but also positioned them as children needing to be cared for by their European ‘father’.

The More You Know: Pro.vin.cial, adj.: of or concerning the regions outside the capital city of a country, especially when regarded as unsophisticated or narrow-minded. Provincialism refers to the byproduct of Eurocentrism. While Europe positioned itself as the center of the world, all other countries were ‘provincialized’, or seen as on the “outskirts” of history, rather than as active participants. Additionally this view strengthened European ideas of non-Europeans as ‘children’, who were uneducated, pagan, ‘backward’, and in need of assistance, or being ‘saved’.

Not until a millennia and several centuries later would the Eurocentric depiction of history be openly refuted in Western academia. Eighteenth century German philosopher, Georg Hegel acts as a prime example of explicit Eurocentrism in historiography. An active supporter of colonialism, Hegel believed that European ‘progress’ did not have any immediate impact on non-European regions and actually showed them the path to ‘freedom’. Although highly rejected today, Hegel depicts a common and severe school of thought followed before the late twentieth century (Copilas, 28-32). These thoughts of European identity heavily influenced how history was written about “others” and perpetuated preconceptions rather than challenging them. Until the twentieth century, Eurocentrism became stronger over time, as imperialist and colonialist actions reinforced preexisting perceptions of Europe and the West as advanced, or even divine.

Historians today are able to study events in the past and understand them as Eurocentric, but why did it take so long for this to become a part of historiographical and social discussion? In the late twentieth century, a movement began known as Postmodernism, which sought to establish that all people had different views of ‘reality’ and no one reality could be seen as the only ‘true’ version of events (Popkin, 146). Today, this is now a much more common understanding of history, but it is still a relatively recent view and application by historians.

One theory of why this view at last took hold in the late twentieth century is due to what Chinese historian, Robert B. Marks, refers to as “the Gap” (Marks, 5). By the twentieth century, the economic gap between “first” and “third” world countries had become so severe and obvious that the direct and indirect effects of colonialism could no longer be denied or hidden. These distinct differences in quality of life inspired historians to retrace the past to understand why these gaps had occurred. As a result, terms like hegemony, anti-colonialism, and Eurocentrism made their way into mainstream discussions. An emphasis on microhistories took hold, as individual and “other” perspectives of historical events were seen as valuable to combating our singular view of history.

The More You Know: Eurocentrism has expanded to include North America, today, and can also be called “Americentrism”.

Examples of Historiographical Eurocentrism

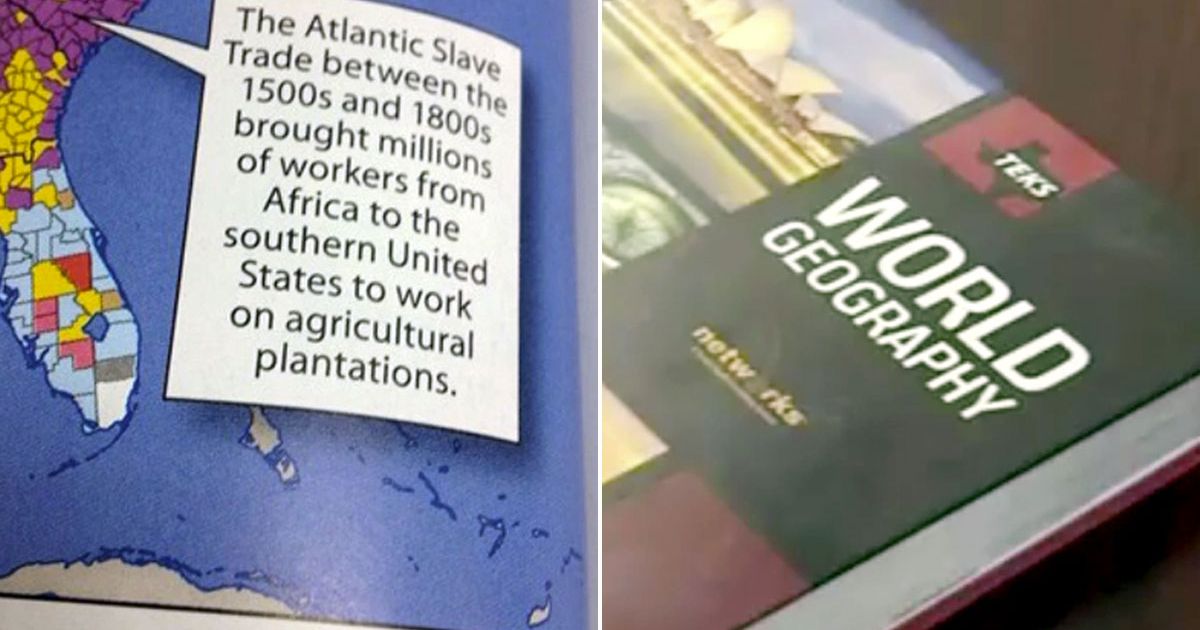

Eurocentrism in Textbooks and the “Discovery” of the “New” World

How did you learn about the history of Mexico and South America in your high school history class or early college courses? Were Europeans portrayed as heroes, or saviors? How highlighted were the genocides which decimated over ninety percent of the indigenous populations (Hamnett, 82)? Was any indigenous context or point of view discussed?

These are the types of questions historiographers have asked since Postmodernism. What was happening on the “other” side of history? But, also, how has the history of Europe and the “other” been portrayed and reinforced through Western education? History textbooks lay a foundation for education and a basic understanding of history, but are also used to propagate Eurocentric and nationalistic ideas (Paez, 211-217). These views create a divide between Europe and the “other” by generating an “Us vs. Them” mentality, rather than a conception of a whole world history (Shohat, 61).

By now, you may be aware that the term “Indian” to refer to some indigenous Americans is offensive, but there is so much more than just a misnomer that has portrayed indigenous Americans inaccurately. While the term “Indian” was a colonial invention, so was the idea of an “Indian” (Bonfil-Batalla, 79). There was no specific identity or trait that indigenous groups used to describe themselves collectively. There were hundreds (if not thousands) of independent tribes which all identified themselves as different from one another as the English and Scotts (Bonfil-Batalla, 76-79). It was not until Spanish arrival that “Indians” were lumped into one identifying category, without acknowledgment of their various cultural differences. Today, some tribes have chosen to reclaim the use of the term “Indian” while others have renamed themselves, such as the Pueblo Indigena, “Original People”, in Latin America (Jackson and Warren, 557). Reclamation and reidentification both act as ways for groups directly affected by Eurocentrism to participate in historiography and revise their history.

Next, let’s briefly discuss Christopher Columbus and the “discovery” of the “new” world. In 1992, unified indigenous groups protested against Mexico’s celebration of “The Encounter of Two Worlds” (Mexico’s counterpart to “Columbus Day”) as the 500 Years of Resistance Movement erupted throughout Latin America (Overmyer-Velázquez, 79). The movement fought the Eurocentric implications of Europe and the Americas as inhabiting two separate “worlds”, as well as the celebration of a traumatic indigenous history (De la Peña, 286). Likewise, the Americas being referred to as the “new” world, aid Eurocentric sentiments that indigenous groups lack a substantial history of their own or that their presence was little recognized when colonists arrived. The Americas are still referred to as the “new world” across multiple academic disciplines, from which we can see that the historiography of a subject transcends the field of history and is applicable to all topics throughout time. This also exemplifies the importance of our use of language as historians when depicting history, as these views often permeate public thought and discussion.

Eurocentric Ideology and the Imposition of Progress

Have you taken the required course “Western Civilization” yet? What does ‘civilization’ even mean?

Civilization is a European concept which describes aspects of European society. So, any culture which defines progress differently, or not at all, is viewed as ‘uncivilized’ and, therefore, not part of European history.

Progress is one of the most overriding Eurocentric concepts which has impacted not only our views of “othered” regions, but has actually impacted their real-world ability to participate in valued (meaning Western) economics, academia, and politics. Western ideas of progress, meaning a continuous improvement of building ideas and inventions over time, depicted non-Western regions as ‘stagnant’, ‘immobile’, or ‘unproductive’. Essentially, when it comes to the ‘progress’ the West has made, it entirely rejects any historical contribution by non-Western regions (Demir and Kaboub, 79). Non-Western regions written about as unprogressive changes how the whole world views their history. Historiography and the importance of how a certain history is written expands far beyond academic history. The opportunities a region has to participate in the current world is ultimately determined by how they have been written about by all people who have chosen to write about them. As the privilege of writing about other cultures was often limited to wealthy, male, European-descendants, those biases indivisibly skewed popular perspectives of those regions.

So, what about cultures that do have ideas of progress, but they are the exact opposite of Western ideals? What about cultures that pride themselves on caring for the earth and not creating waste? Or cultures which value concepts of community sharing and reciprocity over individualism and mass economies? How can cultures like these ever make their way into the vision of a world or human history rather than a Western history?

Eurocentrism in Multimedia

Can you name one film where America is portrayed as the ‘villain’, rather than the hero?

While you might not think of movies, television, or even music as forms of history, these portrayals of Western culture and history are just as, if not more so, important to the reinforcement of Eurocentric beliefs. These resources are available to Westerners as well as the rest of the world. Eurocentric idealizations not only reinforce western beliefs of superiority, but are also used to reinforce “other’s” views of themselves as inferior.

Historical multimedia potentially depict issues as only in the past, rather than as continuous scenarios with long-lasting repercussions for all involved (Lambropoulos, 194). For example, a historical film which depicts slavery as “ending”, such as Free State of Jones, does not really mean that the effects of slavery have ended, but can give that impression to a viewer who does not live with those historical impacts. Or the controversial song, “Deutschland”, by Rammstein, which instigated contemporary arguments against historical events and how they should be depicted. These varying depictions of “popular” histories have as much potential to create contemporary-informed discussion as they do to create a conversational boundary between a Westerner who views history and a non-European who lives with history. These depictions can generate divides, but also offer the opportunity for gaining new perspectives and having discussions about historical events which simply were not possible to have previously.

So, Now What?

There is no cure or quick-fix for Eurocentrism and no way to undo the effects it has had on all societies over time, but through historiography there are ways to analyze and critique its usage and influence its direction in the future. Historiography is used throughout all disciplines and takes part in everyone’s daily lives. How we view and understand the world around us is influenced by how history has been written. It is important to remember that all history has been written by humans and is imperfect and biased. Eurocentrism is just one of the countless influences over the world today, but through recognition and discussion it is possible for us to generate a new understanding of the homogeneous past we have all been told. These sentiments reflect recent pushes to study history as a world history, or even human history, rather than focusing on specific political regions. With emphasis on microhistories and alternative perspectives, non-historians and non-academics have been able to gain access into the scope of historical discussion. These new perspectives allow for open discussions about “truth”, the past, and our history, with the possibility to revise and re-conceptualize what we all think we know.

In an effort to support the expansion of perspectives, the majority of sources for this essay were written by non-Europeans, non-Christians, and/or women.

Bibliography

Araújo, Marta, and Silvia Maeso. Eurocentrism, Racism and Knowledge : Debates on History and Power in Europe and the Americas. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo, and Philip Adams Dennis. México Profundo : Reclaiming a Civilization. Translations from Latin America Series. Austin : University of Texas Press, 1996.

Copilaș, Emanuel. “Hegel, Eurocentrism, Colonialism.” Romanian Journal of Political Science 18, no. 2 (Winter 2018): 27–57.

De La Peña, Guillermo. “A New Mexican Nationalism? Indigenous Rights, Constitutional Reform and the Conflicting Meanings of Multiculturalism.” Nations & Nationalism 12, no. 2 (April 2006): 279.

Demir, Firat and Fadhel Kaboub. “Economic Development and the Fabrication of the Middle East as a Eurocentric Project.” In The Challenge of Eurocentrism: Global Perspectives, Policy, and Prospects, edited by Rajani K. Kanth, 77-96. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Fortin, Ernest L. “Augustine’s ‘City of God’ and the Modern Historical Consciousness.” The Review of Politics 41, no. 3 (1979): 323–43.

Hamnett, Brian R. A Concise History of Mexico. Cambridge Concise Histories. Cambridge [England] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Jackson, Jean E. and Kay B. Warren. “Indigenous Movements in Latin America, 1992-2004: Controversies, Ironies, New Directions.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (2005): 549.

Lambropoulos, Vassilis. The Rise of Eurocentrism : Anatomy of Interpretation. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1993., 1993.

Marks, Robert B. The Origins of the Modern World: A Global and Environmental Narrative from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Century. United Kingdom: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2019.

Overmyer-Velázquez, Rebecca. “The Anti-Quincentenary Campaign in Guerrero, Mexico: Indigenous Identity and the Dismantling of the Myth of the Revolution.” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 46 (2002): 79.

Popkin, Jeremy D. “Glorious Confusion.” In From Herodotus to H-Net : The Story of Historiography. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2016.

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism : Multiculturalism and the Media. Sightlines. London ; New York : Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.