Renaissance Historiography

How Historical Practice Changed Through the Renaissance

By Madeline Whitacre

Renaissance scholars began to develop a humanistic approach to historiography, and historical events began to be thought of in a more secular context. The idea of critical thinking in regard to historical sources further developed during the Renaissance; however, the methodology and traditional ways of thinking about the structure of history were not viewed critically yet.

Humanism

A humanistic approach to history began to develop during the Renaissance. Humanism is a way of thinking that focuses on tangible human causes and influences in the world, rather than addressing God or the divine. Up until this point the primary approach to history had been religious. Individual events in history were important only in that they were part of the larger plan for humanity set out by God. With humanism, the approach to history began to change as scholars studied individual events and people in secular terms. This shift in focus changed the purpose of writing history. The purpose of Medieval historical writing was often to describe or understand the progression of time in terms of Christian theology, which was also seen as an attempt to better understand the divine. With the development of humanism, “the pragmatic purpose [of history] … differed from that of the theological historians by its emphasis on practical, ethical, and moral problems rather than on examples of divine intervention in human affairs.” (Ferguson, 5). While there began to be a shift in the way history was approached due to humanism, the early humanist historians still linked their view of history with their religious views.

One of the early humanist historians, Francesco Petrarch, was born in Arezzo, Tuscany in 1304, and later studied law at the University of Montpellier and then at Bologna. Some of his main works include On Famous Men, Africa, and Italia Mia. Petrarch was cynical towards history as it had been written in the medieval world. He viewed the Middle Ages as an age of decline, after the ideal classical Roman culture and the intellectualism that had gone along with it faded into the past. Despite this cynicism, he believed that there would eventually be a revival of intellectualism and culture, and within this, the study of history would be revived as well. In writing history, Petrarch’s goal was to describe models for “political and moral instruction.” This reflects the traditional view of the purpose of history, which is to provide examples from the past that could teach those in the present. In his Africa, Petrarch discusses not only political issues, but also the moral transgressions of individuals (Petrarch, 208). This focus on moral instruction in particular ties back to the uses of history in the Middle Ages. In addition to his focus on the uses of history, some of Petrarch’s works also contributed to the growing focus on source criticism. He proved that a grant, which had supposedly been written by Caesar and which exempted Austria from imperial jurisdiction, was a forgery.

City-State Chronicles

An important form of historical writing during the medieval period was the chronicle. The goal of this form of writing was to tell what happened without adding interpretation or attempts at determining causation. The chronicle continued to be an important tool during the Renaissance. During this time, the form of the chronicle was particularly associated with the emerging city-states. Many of these chronicles began with the mythical origins of their cities. Through these origins, authors often sought to tie themselves to Roman antiquity. There were still strong ties between the Renaissance chronicle tradition and medieval forms of historical writing, in particular the Renaissance chronicle often sought to tie local and individual events into the established universal history. (Cochrane, 12). Rome continued to be seen as an ideal to strive towards, therefore, successfully associating oneself with ancient Rome provided legitimacy to the city-states that were vying for power and authority.

Although there is considerable continuity between the city-state chroniclers of the Renaissance and the chroniclers of the Middle Ages, there are also some significant developments. While chronicles still focused on describing the ‘facts’ of what actually happened, they also began to include cultural developments that had remained largely unmentioned in medieval chronicles and accounts. In addition to this, there was also a shift in the approach to writing history. While many chronicles still alluded to the divine and the supernatural, much of the writing had a humanist focus. This is particularly true of the sections of chronicles that dealt with contemporary events. The origins addressed in these chronicles often included supernatural events, but the events contemporary to the writers were discussed with a focus on what could be explained by human action.

Giovanni Villani was one of the well-known city-state chroniclers. In his work the Nuova Cronica, or New Chronicles, he focused on his own city of Florence. During his lifetime, Florence was divided politically into the Guelphs and Ghibellines and was being affected by the spread of the plague. Villani followed convention and included in his chronicle the mythical foundation of Florence by Caesar. Villani wrote that “After the city of Fiesole was destroyed, Caesar with his armies descended to the plain on the banks of the river Arno, where Fiorinus and his followers had been slain by the Fiesolans, and in this place began to build a city.” (Villani, 27). As his work approached his own time, Villani described the origins of the political division of Florence, natural disasters, and discussed the cultural development of the city. These developments included “architectural triumphs, the coinage of the florin (which became a standard of exchange), and the career of his contemporary Dante, who … brought honor to his city.” (Kelley, 138). Villani’s deliberate inclusion of culture into his account illustrates a change in how history was approached. Up to this point, there were few explicit descriptions of culture in historical documents and this marks a change in what is considered significant enough to record.

Political and Legal History

Much of the historical writing in the Renaissance focused on the study of political and military history. Scholars working with political and military history approached the subject from a humanistic perspective. The focus of these works was often on particular events and the individuals that affected them. For scholars of political history, the purpose of history was learning from the past and applying that knowledge to contemporary policy and action. The importance of studying history was therefore directly linked to its “great practical value since it teaches moral, ethical, and political lessons.” (Ferguson, 5). It was the role of the historian to describe the truth of the past. These truths were seen as exemplary, and understanding them could impact the present because of the recurring nature of historical events. (Baker, 16). Because of this focus on the history of the political world and how this could be applied to contemporary problems, several scholars of political and legal history worked directly with their governments. Machiavelli had a position working with the Florentine militia, Guicciardini became governor of Bologna, and Chastellain received an official appointment as an historiographer in France. The combination of the humanist elements of history along with the focus on politics allowed for history to develop into more of a profession than it had been previously.

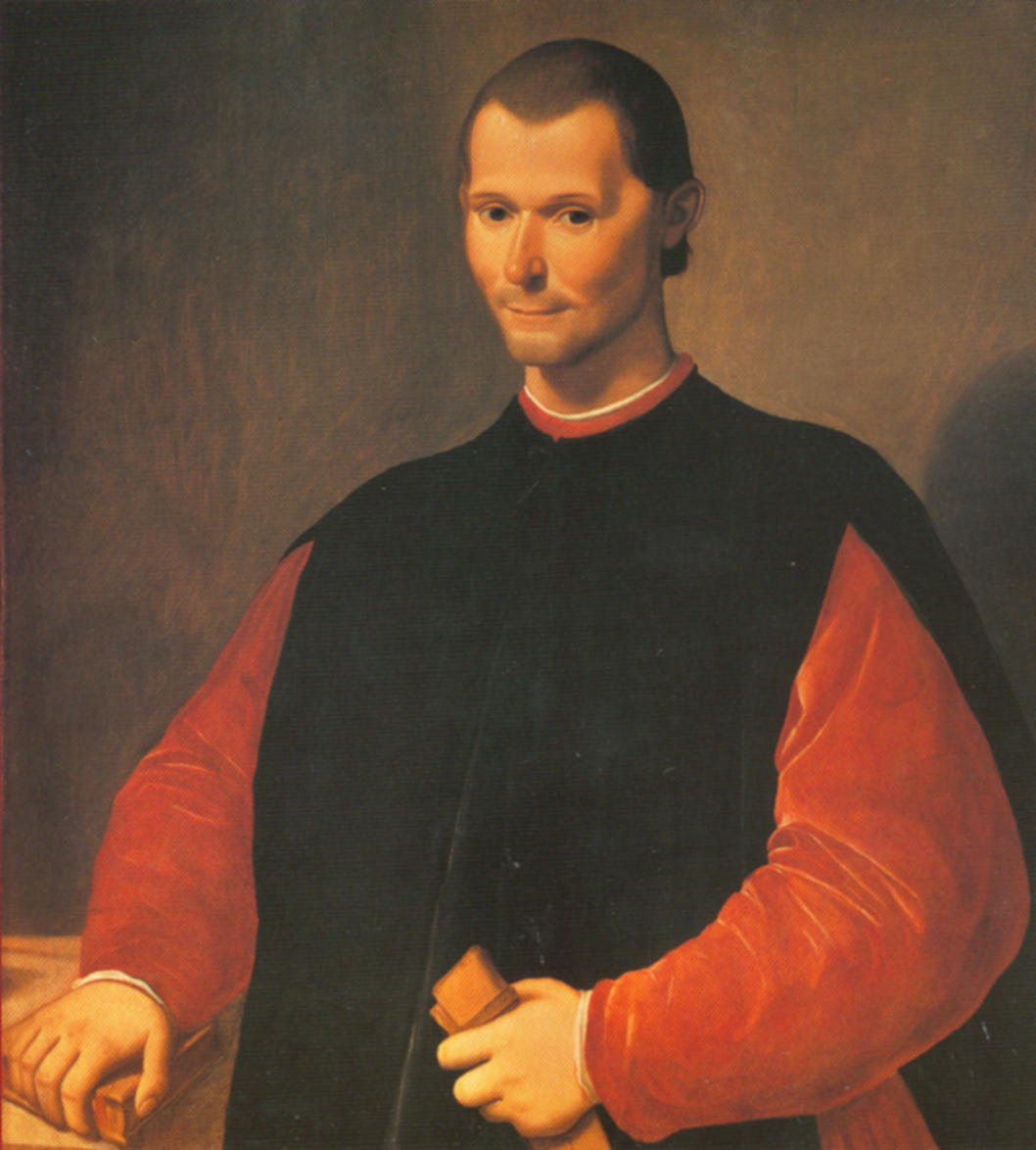

Niccolò Machiavelli, a Florentine, was one scholar who exemplified interest in political history. Machiavelli held an official position in the government and was in command of the militia. However, after a military defeat he was removed from office. He wrote many works, the most influential of which are The Prince, which deals with political axioms, his Discourses on Livy, in which he looks to Livy for answers to many of his political and social questions, and his History of Florence, which was published posthumously. Machiavelli believed that the study of history was essential for political science and for making effective policy. He knew that other fields of learning such as law and medicine had benefitted from knowledge of history, and politics should be no different. In his own work he used this knowledge of history to draw large political lessons, which he believed that when applied, could help instruct and guide political leaders. He states in the History of Florence, “Those serious, though natural enmities, which occur between the popular classes and the nobility, arising from the desire of the latter to command, and the disinclination of the former to obey, are the causes of most of the troubles which take place in cities; and from this diversity of purpose, all the other evils which disturb republics derive their origin.” (Machiavelli, 108). Using events from both Florence and Rome, he discussed this problem of contention between classes, and from this discussion he drew large conclusions, which he saw as being applicable to all politics. He also stated the utility of history in his Discourses, “Whoever considers the past and the present will readily observe that all cities and all peoples are and ever have been animated by the same desires and the same passions; so that it is easy, by diligent study of the past, to foresee what is likely to happen in the future.” (Kelley, 148). In his writing on the past of Florence, Machiavelli used both humanist and chronicle sources. His use of these sources was rather subjective as he shaped his historical narrative to fit his political ideas.

Another of these politically and militarily focused historians was Francesco Guicciardini. Guicciardini’s interest in this subject came from the unrest of his own time, particularly the invasion of 1494. Charles VIII of France had invaded and captured Naples, but was subsequently driven out by Maximilian I of Spain and the Pope. Like Machiavelli, Guicciardini was interested in understanding political change through the study of history. He analyzed the invasion in detail, and used archival sources to do so. Guicciardini was particularly significant to the continuing development of humanism in that he focused much of his work and research on the character of the major individuals who had been involved. In his work The History of Italy, he spends a significant amount of time describing the background and temperament of each of the individuals involved.

Ferdinando of Aragon, King of Naples, was of the same disposition: a very sagacious prince and highly esteem’d; tho’ formerly he had discovered an ambitious and turbulent Spirit. He was instigated, at this very Time by Alfonso, Duke of Calabria, his eldest son, to resent the Injury done to Giovanni Galeazzo Sorza, Duke of Milan, who had married Alfonso’s Daughter. (Guicciardini, 5).

Guicciardini paid close attention to these individuals as he created his narrative, going into detail about their disposition, family and political ties, and motives. This inclusion of the study of the individual set Guicciardini apart from Machiavelli and other historians of the time. He explained history not by sweeping and inclusive theory, but by understanding things on the individual level. In this way, Guicciardini wrote with much the same approach that Thucydides did.

Cultural History

Although much of historical writing in the Renaissance focused on political and military history in the Thucydidean tradition, there were also several developments in the realm of cultural history. Far more cultures were being included in the western historiographical canon. Among these groups that had not previously been part of the western historical scope were the Jews, Babylonians, Indians, Persians, Egyptians, and Chinese. Up to this point, the intellectualism of antiquity had been the ideal, but in the Renaissance the idea of historical ‘progress’ began to emerge. Scholars believed that reason and intellectualism were present in the Modern era, and this belief helped to expand the study of cultural history, and “the Moderns had to follow their own lines of inquiry and thought.” (Kelley, 156). Rather than focusing only on subjects and eras that tied to Rome, the study of history was expanded to include these cultures that had not traditionally been part of historical thought.

Polydore Vergil’s historical works helped to develop the expanding field of cultural history. Vergil was educated at the University of Padua and ordained in 1496. One of his works was De Rerum Inventoribus, a humanist encyclopedic approach to history that included the whole range of humanist studies. The themes of this work included traditional historical subjects such as political structures, law, and religion. However, it also included topics that had not traditionally been included in historical writing such as marriage, painting, commerce, and technology. (Vergil, 4-7). Vergil approached history broadly, as a way to organize and interpret human culture.

The New World

The way history was viewed was also impacted by the discovery of the New World. The discovery of an entire hemisphere that had been previously unknown and its native inhabitants was disruptive to the classic approach to history. How did this new land with its new people fit into the classic European story of translation of empire and the four monarchies? The new world was written about within the context of Spanish Renaissance Historiography. Historical accounts of the new world were influenced by traditions of chronicles, universal histories, and myth, as well as emerging approaches such as humanism and historical criticism. The narrative of the new world became the story of the expansion of European power and empire, with American natives represented as barbarians and Europe represented as the new Rome.

Bibliography

Baker, Herschel, The Race of Time (U.S.A., University of Toronto Press, 1967).

Cochrane, Eric, Historians and Historiography in the Italian Renaissance (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1981).

Ferguson, Wallace K, The Renaissance in Historical Thought (New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948).

Guicciardini, Francesco, Storia d’Italia (1537-1540); English Translation: Austin Parke Goddard, “The History of Italy, from the year 1490, to 1532. Written in Italian by Francesco Guicciardini.” (London, John Towers, 1754).

Kelley, Donald R, The Faces of History (London & New Haven, Yale University Press, 1988).

Machiavelli, Niccoló, Storia di Fiorentine e delle cose d’Italia (1532); English translation: Felix Gilbert “The History of Florence and the Affairs of Italy” (New York, Harper & Row, 1966).

Petrarch, Francesco, Africa (c.1338); English translation: Thomas G Bergin & Alice S Wilson, (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1977).

Vergil, Polydore, De rerum inventoribus (1581); English translation: Thomas Langley, “A Pleasant and Compendious History …” (London, Printed for John Harris, 1686).

Villani, Giovanni, Nuova Cronica (c.1348); English translation: Rose E Selfe, “Villani’s Chronicle” (London, Archibald Constable & Co, 1906).

All figures via Wikimedia Commons, (Fransesco Petrarch) (Niccolo Machiavelli) (Giovanni Villani).