Marxist Historiography

A brief overview of Marxist beliefs, development, and expansion.

By Heath Skroch

From the bloodshed of the Bolshevik Revolution to the fall of dynastic China, Marxist values have had a massive impact on the course of human history. This economic theory requires a deep understanding of social interactions. Marxist ideologies have their core in human interaction as well as the struggle between economic and social classes.

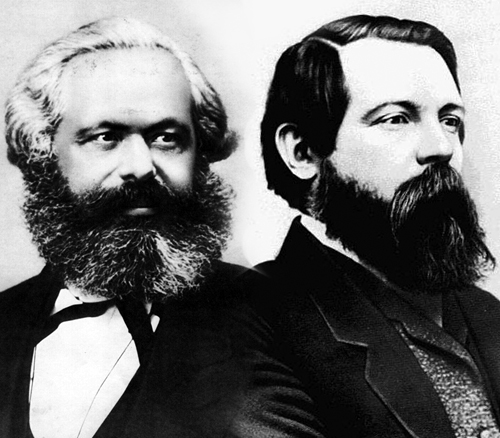

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engles

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engles were two German philosophers who lived in the 19th century. The two met in Cologne, Germany and would ultimately become close friends and partners with the goal of furthering the growing socialist movement. The two were instrumental in helping with the formation of the Communist League; and later at the second communist congress in London (1903) they drafted the Communist Manifesto. After this, the two continued to work towards the full implementation of their ideologies across Europe. The Revolutions of 1848, an attempt by the Germans to overthrow their authoritarian government, proved to be an opportunity for spreading their economic and political beliefs that ultimately failed along with the Revolutions themselves. The two continued publishing books on Marxism and spreading their thoughts until their deaths.

Marxist Beliefs

Marxist ideology is based on a Philosophical Anthropology, a theory of history, and an economic and political program. The core of this philosophy lies within the interaction between social and economic classes. Their original ideas were based in economic aspects of society in which they divided the population into the Bourgeoise, capitalists who owned the means of production, and the Proletariat, the working class who had no other means to survive than by selling their labor. It was the belief of Marx that the Bourgeoise was exploiting the Proletariat by making a profit from their labor. These two classes as well as their social and political arrangements are what encompass the “relations of production.” These relations are what make up the superstructure of society, that being the laws and governmental situations that allow the continuation of capitalism.

Although postmodernism did not appear untill the mid 20th century, when it comes to Historiography, Marxists adopt a structuralist view of society with certain elements of postmodernism. This can be seen firstly in the understanding that history is often written by the upper class of a society for specific purposes. These include justifying their position over the lower classes, or in the case of Marxist beliefs, to continue the capitalist system. In this way Marxist beliefs are extremely postmodernist as they question the biases and goals of those writing history. Marxist believe the upper class has created both history and the various structures contained within it.

Historiographical progressivism can be described as a belief that throughout history humanity has been on a gradual incline, in terms of development, towards an overall end goal. The way in which Marxism embodies this characteristic can be most clearly seen in actual Marxist texts. For example, in Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals Faulkner states: “For the last 5,000 years, ever since the Agricultural Revolution first made possible substantial accumulations of surplus wealth, humanity has been engaged in an uneven and uncertain ascent towards the abolition of want.” (Faulkner) In the case of Marxism, this end goal is the eradication of poverty under the capitalist system. The ultimate goal lies at the end of humanities linear progression through early economic systems such as feudalism and Mercantalism, to Capitalism, through Socialism, and finally culminating with Communism.

This Marxist progressivism ties together many historical events especially those having to do with class conflicts and developments in capitalism, in a way these can be seen as the “engine” of change. Many Marxist histories focus on the Mercantilist Revolution as the first “version” of capitalism. This is because it is marks the first time non-noble individuals could accumulate vast wealth and thus invest it. Through Marxist progressivism this singular even can be tied to all others having to do with the progression from capitalism to communism. In that way the invention of the mercantilist system is the predecessor of Industrialized Capitalism, Regulated Capitalism and especially of countries in the modern day that have socialist and even communist systems.

Marxism and Government

As previously stated, Marxism holds a certain degree of contempt for any capitalist society’s government. This can best be explained in Marx’s own words in the preface to his 1859 writing, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Here he states: “Legal relation as well as forms of state are to be grasped neither by themselves nor from the so-called general development of the human mind, but rather have their roots in the material conditions of life…” Marx explains that it is the material conditions of life, otherwise known as the social and economic class are what ultimately shape the laws and government of a society. He then connects this to the writing of history saying, “Economic production and the structure of society uprising there from constitute the foundation for the political and intellectual history of that epoch…”

Problems around the writing of history, such as the purpose of writing and bias of the author, were nothing new; however, Marxist Historiography places this criticism at the core of its beliefs, going as far as to differentiate itself from “regular history’ by calling it “bourgeois history.” In this case Marxists assert that this “bourgeois history” is created by the government in order to justify the capitalist system. It is for this reason that for Marxists, non-Marxist historians should be, first and foremost, “denounced” as ‘falsifiers of history’—made positive evaluation of bourgeois authors dependent on their politics and on their affinity to an orthodox materialistic understanding of history. (Mogilnitsky, pg 414)

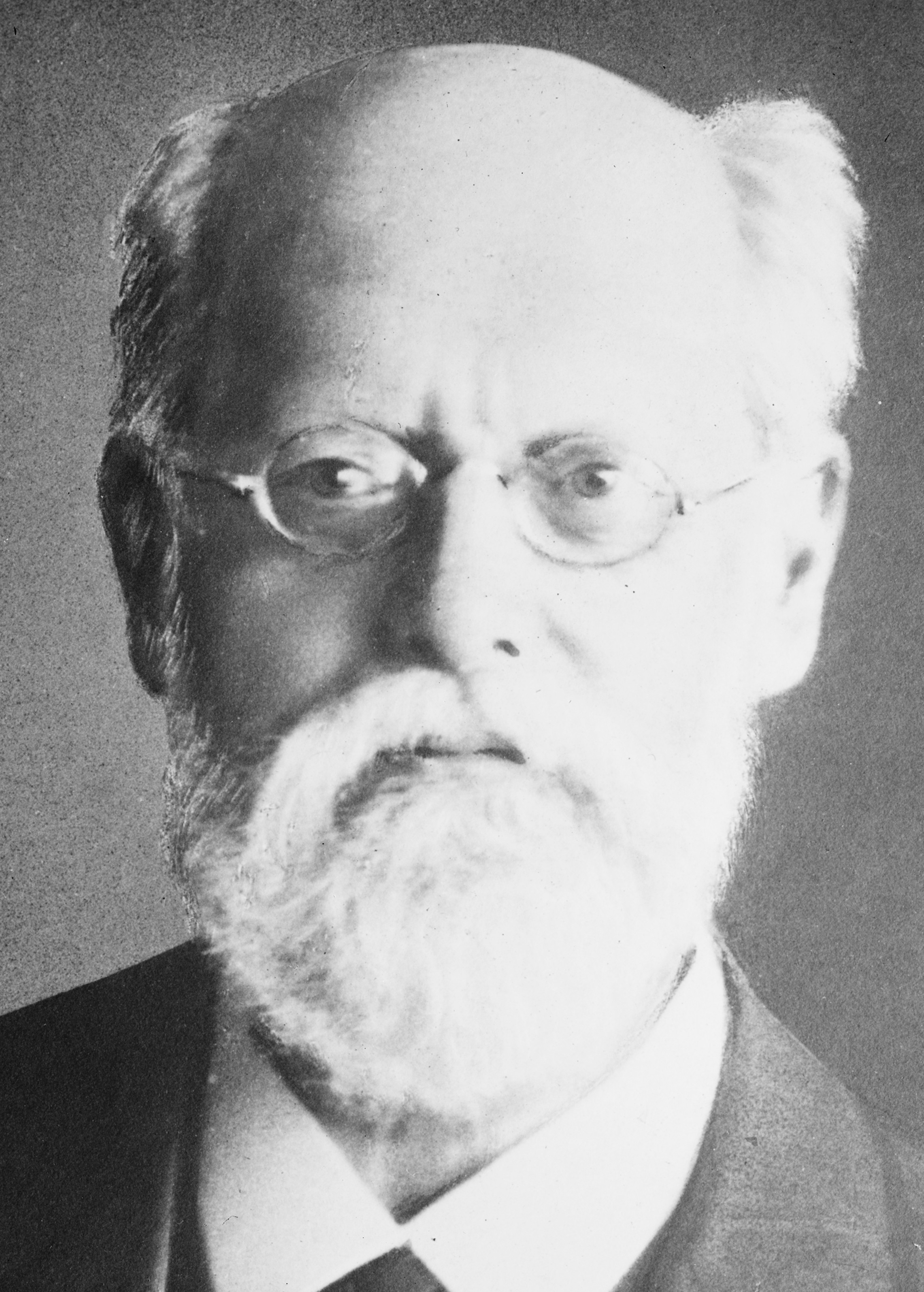

Kautskism

Karl Kautsky (1854-1938) was a Marxist theoretician who lived from the mid 19th century to the mid 20th century. Despite disapproval by Karl Marx, who used the word “mediocrity” to describe him, Kautsky was a leader within the Marxist community. He began his career as an editor for Marx working on such publications as Theories of Surplus Value. He did such an impressive job that he later became the editor of Marx’s estate after Fredrich Engles’ death. He was so effective at his job that he quickly became known as the most important theorists in the Marxist World; doing so much to popularize Marxism in the west that he earned the title “The Pope of Marxism.” Kautsky wouldn’t hold a high title in the Marxist party for long as several disagreements with Lenin over the Bolshevik rebellion and support of the first world war led to the end of his political career. It was due to his more available schedule that he would be able to write more philosophy and ultimately create a new branch of Marxism that is often called Kautskism.

Kautskism can be seen as a more strict adherence to the historiographical belief that society was ever progressing towards a lower class uprising. This originated from Kautsky’s claim that Russia was not ready for a socialist revolution as the country had never had an unrestricted capitalist economy. This embodies the linear history of his ideology as, in his opinion, a country couldn’t skip a step on the path to communism, especially if it surpassed his own. This view lead many critics of his time to label Kautsky as a “determinist” or “Darwinist.” Kautsky made sure to emphasize that his position was grounded in the human agency throughout history being the driving force behind the inevitable Proletarian uprising. Kautskism only slightly avoids the label of determinist in that it doesn’t advocate for “inevitable, linear history” but rather that the workers of the proletariat would eventually overthrow the upper class.

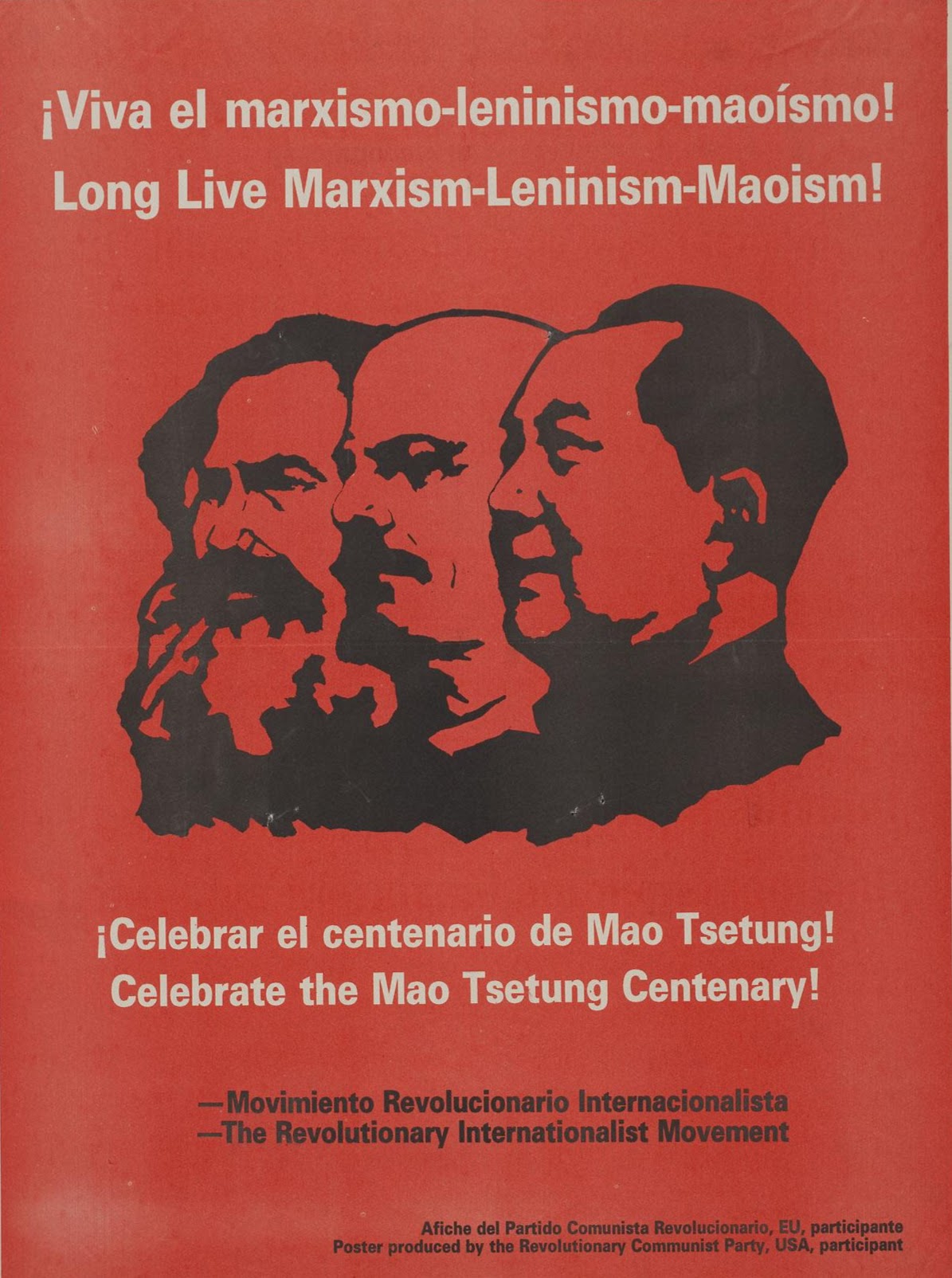

Marxism-Leninism

Almost the entire twentieth century of Russian History was defined by Marxism. This reign of Marxist ideology began in 1917 with the Bolshevik Revolution, (also known as the Russian Revolution) lead by Vladamir Lenin. This event is extremely important as it led to the rise of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union). Lenin placed himself as dictator of this new government and pushed for the classic Marxist support of a proletarian democracy. Additionally, he pushed to nationalize banks and much of the Russian economy.

Shortly after Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin rose to replace him as Soviet dictator. Propaganda under the new dictator became extremely common, all of which sought to justify Stalin’s position and Marxism as the correct ideology. With the use of a police state Stalin was able to nationalize agriculture and industrialize Russia; with the threat of death for all those who refused to comply. Additionally, Stalin pushed for rewrites of history, mythologizing his early life and increasing his role in the Bolshevik Revolution.

The importance of Marxism in Russia is that it served as the first place that the ideology could truly be tested. Furthermore, it allowed the ideology to spread with the expansion of the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence.

Marxist History in China

For the vast majority of history in China, dynastic monarchy was the only form of government. This system of government was shortly broken by the Republic of China from 1912-1949, before ultimately being succeeded by a communist state. Marxism greatly expanded in the two decades before the Chinese Communist revolution. Fan Wenlan lead the Marxist view of Chinese History, opposing historians who followed a more nationalist view. Firstly, Wenlan believed in the classic linear Marxist view of history, believing that the communist revolution would be the culmination of the centuries long struggle of the Chinese people against feudalism and imperialism. (Li, pg 272) Oddly enough, in a way the short period of The Republic of China was required for this linear history to work. In juxtaposition of Kautsky’s view of the Russian Marxist Revolution, China had fully experienced the “steps” to becoming a communist state.

After the success of the communist in the civil war, Fan Wenlan became the foremost authority on Chinese history; with his revolutionary narrative becoming the accepted story of Modern Chinese History. With the rise of Marxism, the nationalist viewpoint became known as “bourgeoise history.” Additionally, western powers began to be viewed as malicious for the various acts of violence committed under imperialist policies. The greatest of these was the opium wars, in which the Chinese attempted to stop the trade of Opium from European merchants; being easily defeated by the far more militarily advanced Western powers. These wars offered the perfect chance to highlight Marxist beliefs due to the corruption of the Chinese government at the time. Chinese Aristocrats worked with European Opium traders to make massive amounts of profit at the expense of the welfare of the Chinese population; even going as far as to oppose the legalization of opium in order to keep its price high. This allowed for the demonization of the Chinese government and acted as an example of the injustices suffered by the Proletariat from the Bourgeoise. Fan capitalized on this, citing it as another reason that the Marxist Revolution was inevitable.

Marxist History in Japan

With the close of the second World War, Japan found itself defeated and placed under military occupation by the United States. This occupation involved nearly one million Allied soldiers and present a fertile opportunity for Marxist enthusiasm to grow. When the occupation did finally end, many Marxists argued that American “colonization” had worsened under the system of capitalism and imperialism. They saw American influence as a negative, understanding themselves to be in the Proletariat position and the United States to be the Bourgeoise. Historians such as, Ishimoda Shô saw the solution to this external influence to be a strengthening of the “cultural core” of the Japanese people. This would hopefully lead to the country no longer having classes and being free from the influence of capitalism. The outbreak of the Korean war in 1950 increased anti-colonial fever in Asia which greatly boosted Marxist ideals.

Oddly enough, the recent Marxist revolution in China served as an example for the Japanese Marxist despite the Chinese Revolution being heavily driven by Japanese imperialism during World War II. (Gayle, pg 86) This strange colonizer and colonized relationship required Japanese Marxist historians to argue that the nation, comprised only of the people and their culture, was indeed separable from the state, or government.

Conclusion

Marxist Historiography stands at the core of Marx’s economic philosophy. With its view of linear history, social class structures, and almost prophetic view of the future Marxism continues to be relevant today. This way of viewing the past and thus preparing for the future can best be seen in communist societies; and those of socialist socialist economic systems which are understood to be “on the path to communism.” Its greatest impact is brining proletariat struggles to the forefront of modern thought. With many countries experiencing Marxism with various historians, the belief systems impact on the world continues to grow.

Bibliography

Blackledge, Paul, and School of Social Sciences. “Karl Kautsky and Marxist Historiography.” 1 Aug. 2006

Chalcraft, John T. “Pluralizing capital, challenging Eurocentrism: Toward post-Marxist historiography.” 2005.91 (2005): 13-39.

Faulkner, N. (2013). Marxist History of the World : From Neanderthals to Neoliberals.

Gayle, Curtis Anderson. Marxist History and Postwar Japanese Nationalism. 1st ed, 2002.

Irfan Habib. Problems of Marxist Historiography. 1988;16(12):3-13.

Li, Huaiyin, Between Tradition and Revolution: Fan Wenlan and the Origins of the Marxist Historiography of Modern China, 2010, 0097-7004

“Marxism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica

Mogilnitsky, B. G. (1992). Non-Marxist Historiography of Today: The Evolution of Its Theoretical and Methodological Principles¹.

Nolte, Ernst. “The Relationship between ‘Bourgeois’ and ‘Marxist’ Historiography.” History and Theory

Wang, Q. “Marxist Historiographies: A Global Perspective.”

Zahoor, Muhammad Abrar, and Fakhar Bilal. “Marxist Historiography: An Analytical Exposition of Major Themes and Premises .” 2013.