History of Archival Theory

A Brief History of Archives and Archival Practices

By Karli Snyder

Archival sciences emerged in the 1890s as a method of scientific theory that professionalized the practice. With objections to the unpopular “Grand Narrative” format of pre-modern historical traditions and the splintering of postmodernist views of history, archival sources have never been more carefully scrutinized, categorized, and mined for information. How did we get “from then to now” with the practice of archival record-keeping, and who were the key figures responsible for establishing the modern methods of archival theory? A better knowledge of how archival science emerged is integral to historical research. This knowledge will allow modern historians more consensus and tools for source criticism and debate.

A Very Brief History of Archives

Since our earliest conception of a social framework, humans have desired to transmit messages and information across time. Our earliest ancestors did this by leaving behind images and symbols on permanent mediums like rocks and in caves. Examples of these messages exist today all over the world. The development of the earliest writing systems, which served to displace oral transmissions of information, began to take shape starting c. 3300 BCE, as seen in places like Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica. These written records were created upon various mediums such as clay tablets, stone, linen, parchment, or papyrus (Delsalle, 3). The development of written records or other forms of tangible information corresponded to the creation of archives. Archives are defined as the records, documents, and materials which provide information about a place, institution, events, or a group of people.

Classical Greeks and Romans wrote many of their records on wooden boards, parchment, and papyri scrolls, all of which eventually supplanted the older traditions of orally transmitting information and committing it to memory. The emergence of physical, tangible records prompted the creation of physical repositories. The ancient Athenians created a building called the Metroon between 390 and 370 BCE, which was dedicated to collecting and storing their citiy’s public and private administrative records. Ancient Romans followed suit and erected buildings to house transcripts of the Roman Senate’s proceedings beginning in 59 BCE. Many records were stored in the Tabularium, a prominent building in Rome that overlooked the forum (Delsalle, 17-24).

Classical record-keeping practices influenced how and what was archived from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Era in Western Europe. According to archival historian Paul Delsalle, the centuries between the end of antiquity (fifth century coinciding with the fall of Rome) and 1100 lacked in systematic record-keeping, or it simply did not exist (Delsalle, 65). Beginning in the twelfth century, churches and cathedrals became repositories for records dealing in law codes and private transactions, particularly those related to church property and bookkeeping records. Eventually, chanceries (offices where notaries drew up various documents) would become the repositories of most non-religious documents, especially those related to royal decrees and legislation. The Englishman, Walter Stapledon (who was Treasurer of England and Bishop of Exeter in the early 1320s) was tasked with reorganizing all of the records of the English royal archives held in the Tower of London. Because of the records confusing lack of organization, he introduced finding aids to index and reference particular documents for easy access.

Due to various social and political developments, European archival management became local and centralized between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. The movement to create a central repository of state and private records first appeared in Florence, Italy, under the rule of the Medici family and their establishment of the legal and administrative offices of the Uffizi. The most extensive national collection began with the Spanish colonial archives housed in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville. The Archivo became the repository of the massive amounts of information kept on the colonies of the Spanish Habsburg empire and its extensive business and administrative matters. Central national collections were also created for the Dutch colonial archives, which reflected the Netherlands’ business and accounting records from the country’s widespread trade and colonial enterprises (Delsalle, 113-114).

The Establishment of Archival Theories

Once archives and the records they housed were centrally located and run by state bureaucracies, the need for dedicated archivists emerged. Along with the rise of the archival profession came the necessity of deciding on what formal organizational rules needed to be established and what records were worth preserving. Archivists began using more scientific methods to address the organization and sorting of records that arose during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In order to understand how these theoretical methods developed, it is essential to identify the central theoretical ideas behind them and to appreciate the contexts in which they were formed.

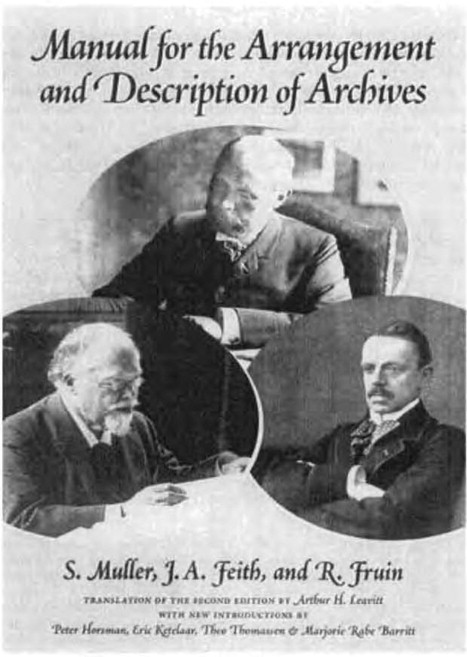

The Dutch Manual

The establishment of specialized archival schools began in the early 19th century and was centered in Italy, Germany, and France. Experiential anecdotes and some formal studies on how to best catalog and organize records were vital components of these institutions. However, it was not until 1898 that a systemized guidebook was published. Written by a group of three Dutch archivists, Samuel Muller, Johan A. Feith, and Robert Fruin, the Handleiding voor het Ordenen en Beschrijven van Archieven (Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives), or The Dutch Manual, would become the early 20th century basis for most archival theory throughout Europe, Asia, and North America (Moats, 2).

The Manual’s primary theoretical practices establish three main archival rules: arrangement, description, and provenance. Arrangement is related to an archivist’s attempts to re-establish the original order of records and reflect how the information was organized by the person(s) or institution(s) that created them. Description refers to the terms and labels used by the archivist to identify records and make them searchable. Provenance is how the various records were created, accumulated, or maintained by the creator of the records for their use. The last main principle established by the Manual is that of Respect des Fonds, or the concept of keeping records separated according to their provenance or origin (Horsman, 253).

The Manual was written during a period of significant change in the international power structures of governments and nations and its theories reflected changes in technology and industry. With the rise of new communication technologies, the Dutch archivists wanted to parallel this desire for speed and efficiency by streamlining the ability of the archivist to consolidate and standardize archival methods of record organization and establish a set of guidelines to adhere to. After its initial publication, it was rapidly translated into German, Italian, and French. A second French edition was then used in the USSR by 1920, and in 1940 the Manual was translated into English. The widespread dissemination of the Dutch Manual allowed for the codification of archival theory. However, it was also criticized for its inability to allow other theory forms to emerge since it did not recognize different interpretations of its guidelines (Ridener, 34).

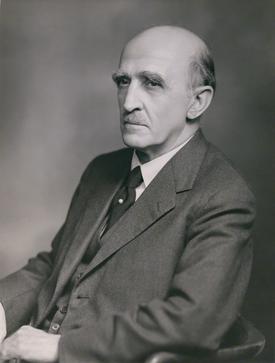

Sir Hilary Jenkinson and the Custodial Archivist

Sir Hilary Jenkinson (1882-1961) was a British archivist and archival theorist whose own published manual profoundly affected the archival profession. His work titled A Manual of Archive Administration was published in 1922 and revised in 1937. His theoretical approach was centered on the basic guidelines given by The Dutch Manual, but he also expanded the practice and theories it contained. His definition of archives and records was more conservative than that of the authors of the Manual, and he specifically wrote against the idea of archival appraisal. This belief was a hugely conflicting matter. Jenkinson did not think that archivists should select and destroy particular records of any type and stated that this was to have been the work of the record creator instead (Ridener, 57).

“It does not seem much to demand that any one who is to take upon himself the responsibility of destroying irrevocably Archives which have come down to us from the past should do so on something more than a consideration of his own interests and those of the time in which he lives: he should surely regard himself as a trustee for the future as well as for the present. But in that case who is to fill the role? Who can project himself into the future and foresee its requirements?” (Jenkinson, 147).

The idea of record destruction was complicated, even when getting rid of duplicate documents or records. Jenkinson’s idea was that the archivist was not to be put in the decision-making role regarding what was kept and what was destroyed. Rather, the archivist was to be an impartial custodian of records instead. The fundamental role of the archivist was to preserve all materials in the archive for future use and for whatever future needs may require.

Jenkinson also believed that archives were the accumulations of records to be kept together in the archive once created together. His definition of records was based upon the concept that archives were strictly defined as materials created for three distinct audiences: material received by an office, material created for external audiences, and material created for internal audiences (Jenkinson, 23).

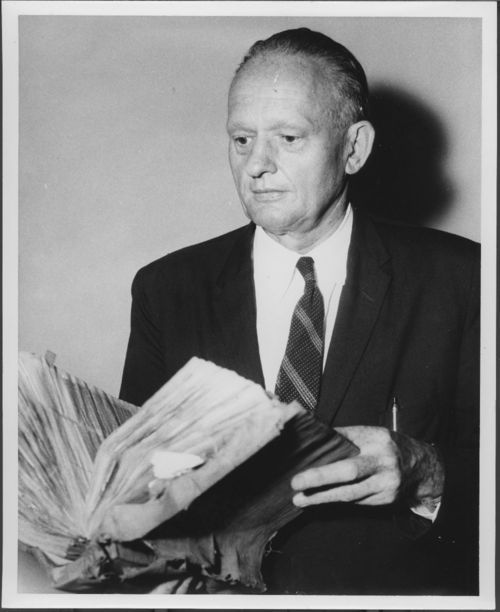

T.R. Schellenberg and the Rise of the Modern Archivist

T.R. Schellenberg (1903-1970) was an American archivist who published works on modernizing archival theories. In contrast to Jenkinson, whom Schellenberg noted was an important figure in the early formation of archival theory, the appraisal of records was fundamental to the modern archive. Schellenberg wrote his most important work, Modern Archives: Principles & Techniques in 1956. He documents the importance of the archival institution, defines what an archive is, and discusses the differences between archivists and librarians. His most critical point is that the modern archivist needs to use appraisal techniques to create an invaluable collection of records.

Archival appraisal is a term used to describe the selection of particular documents or records that the archivist assigns an essential value to, either as a present record or as a record or document for future use. If a record is deemed unnecessary to the institution it is housed in or does not merit preservation based on a set of guiding standards, it is destroyed. This technique empowers the archivist to choose what is worth being saved for posterity, which created significant controversies within the profession that still exist today.

“Archivists of various countries have attempted to formulate standards by which to judge the values of records. These standards serve as guidelines to steer the unwary through the treacherous shoals of appraisal work. They are often little more than general principles. They can never be regarded as absolute or final. They should always be applied with judgment and common sense.” (Schellenberg, 133).

Schellenberg was working from a model of archival appraisal that he instituted during his time employed by the United States Federal Government, which created and retained a copious incursion of documents and records of all types and varieties. Faced with this onslaught of materials and limited storage space, Schellenberg set out to define what appraisal criteria should be and used three main points of valuation; uniqueness, form (material of the record), and importance (Schellenberg, 63).

Feminization of the Archival Profession

The rise of the professionalization of archivists has been linked to the role of women since the 19th century. In the 1880 British Library essay entitled The enemies of books, a clear line is drawn between women in roles of domestic caregiving and as preservers of books. It states that the best way to care for books is to “treat them like your children,” who would become sick if left in poorly kept environments (Lapp, 221). Women employed in both the public and private sphere were typically given duties as secretaries, bookkeepers, librarians, and archivists. These jobs inherently require close attention to detail, especially regarding active record keeping and organization, and some employers felt women particularly possessed these ideal qualities.

As archival roles have evolved, primarily due to competing theories, care ethics have been greatly emphasized in modern archives. Archivists are no longer viewed as simply caretakers but now are seen as providing care and responsibility toward records, users, and subjects of the records themselves. This notion of providing something for others had allowed for the role of archivist, mainly when filled by women, to be held as less professional than other academic disciplines. Many modern feminist scholars link the idea of the physical repository to that of the domestic home, and it was similarly understood that because of women’s traditional maternal roles, women are also excellent communicators and have direct leadership in preserving memories and histories (Lapp, 224).

The continued feminization of archival professions, including museum administration and library sciences, is backed by statistical studies in labor markets. As the need to archive and administer the immense amount of data and records increases, women’s roles have become more prevalent in these academic fields.

Modern Challenges of Archives

Modern archives and the professional archivists involved in their care face challenges on two fronts: the need to represent diversity and inclusion of overlooked records and the quandary of digital archives and research. These two dilemmas present the fundamental challenges to established theoretical paradigms.

Older paradigms of theory have often (or completely) overlooked the importance of appraisal of records regarding generally excluded and culturally minimized information, leading to a sense that most archivists have been prejudiced in their practice of selecting or excluding particular archival records. One of the most influential modern archivists was Canadian Terry Cook (1947-2014), who wrote about the increased need to create wholistic and inclusive archives by explicitly working with minority communities in order to preserve their “collective memories” (Cook, 183). Cook saw these ‘archival silences’ as highly detrimental to the health of democracies worldwide and urged novice archivists to include community participation in archival planning as a means of granting ‘archival dignity’ to the minimized voices of the past and present.

“How well we meet the challenge for more democratic, inclusive, holistic archives may determine how well we flourish as a profession in this digital century.” (Cook, 194).

Digitization of archival records now presents obstacles in defining whom the archival records are preserved for and how they are used. According to archival scholar Enrico Natale, there is an ever-widening gap between digital archives and the historians that utilize them (Natale, 8). He states that with the rise of personal computers, the digitization of archival documents and records, publicly accessible databases, and the internet’s popularity, far fewer researchers visit archives to examine records or search using hard copies of finding aids. The most impactful issue on archival preservation is the computerization of information searches. Modern archivists are grappling with not only the need to make digital finding aids and searchable databases available but are scrambling to find ways to digitize and systematically update outdated technologies that become obsolete within a short amount of time. The primary use of search engines has also posed a challenge for archivists to be well-versed in the collections they care for and understand basic computer technologies and their impacts on archives in the future.

The archives and the theoretical methods used to create, categorize and use them have been an understated influence in the writing and dissemination of historical research and narratives. The figures from the late 19th century who began to use more scientific and streamlined parameters to help organize and make records user-friendly have added to the debate over what an archivist is responsible for. As the 21st century has brought incredible changes to how data is created and maintained, the archivist has an even more prominent role to fill in the way society will see itself far into the future, which is extremely powerful.

Bibliography

- Cook, Terry. “‘We Are What We Keep; We Keep What We Are’: Archival Appraisal Past, Present, and Future.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 32, no. 2 (October 2011): 173–89.

- Delsalle, Paul. A History of Archival Practice. Procter, Margaret, trans. Routledge, 2018.

- Horsman, Peter, Eric Ketelaar, and Theo Thomassen. “New Respect for the Old Order: The Context of the Dutch Manual.” The American Archivist 66, no. 2 (2003): 249–70.

- Jenkinson, Sir Hilary. A Manual of Archive Administration Including the Problems of War Archive Making. Clarendon Press, 1922.

- Lapp, J.M. “Handmaidens of History: Speculating On the Feminization of Archival Work.” Archival Science 19, (2019): 215–234.

- Lustig, Jason. “Epistemologies of the Archive: Toward a Critique of Archival Reason.” Archival Science 20, no. 1 (March 2020): 65–89.

- Moats, Rachel. “An Introduction to Archival Practices.” International Social Science Review 94, no. 1 (January 2018): 1–9.

- Natale, Enrico. “Digital humanities and documentary mediations in the digital age.” Dobreva, Milena, ed. In Digital Archives: Management, Access, and Use. Facet Books for Archivists and Records Managers (Facet Publishing, 2018): 3-21.

- Ridener, John. From Polders to Postmodernism: A Concise History of Archival Theory. Litwin Books, 2009.

- Schellenberg, T.R. (Theodore R.). Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques. University of Chicago Press, 1956.

- Sternfeld, Joshua. “Archival Theory and Digital Historiography: Selection, Search, and Metadata as Archival Processes for Assessing Historical Contextualization.” The American Archivist 74, no. 2 (2011): 544–75.