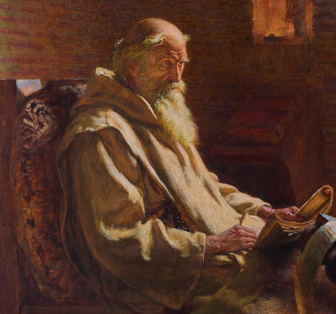

Bede

A Case Study in Medieval Historiography

By Eamon Bisbee

Introduction and historical context

What year is it? As I write this, 2019 is nearing its end. But why is this year numbered in this way? You are likely aware that the system of numbering years is derived from the medieval Christian system known as “Anno Domini’’, literally meaning “in the year of our lord”, referring to the birth of Jesus Christ. But how did this system of dates come to be so widespread, literally used around the world? The credit for this widespread use can be given to Bede, an 8th century historian whose works popularized the anno Domini system and whose historical methods were far ahead of his time.

In some cases in the study of historiography, as in M. C. Lemon’s The Philosophy of History or Eileen Ka-Mey Cheng’s Historiography: An Introductory Guide*, the whole medieval period from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 AD) to the beginning of the Renaissance (circa 1350) are ignored. Lemon in particular, might argue that Bede’s work was not part of a major philosophical shift in Historiography. ‘Historians’ in the medieval era are often pictured as mere chroniclers doing little more than listing events, or else seen as so biased or backwards that their finished works and methodology alike are considered unworthy of notice. It is true that many well-known works of history do fit this model, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. However, this is not always the case. There were many medieval historians whose methods and works might be thought of as ‘ahead of their time’. One such scholar is Bede (c. 672-735), commonly known as the ‘Venerable Bede.’

Bede was born in the north of England, in what was then the independent kingdom of Northumbria, more than a century before Anglo-Saxon England was unified into one country. At the age of seven, Bede entered the monastery of Wearmouth where he was educated, and later moved to its twin monastery of Jarrow at its founding in 682. By the age of 30, around 703, Bede was ordained as a priest, and aside from his other duties he was “particularly drawn to study, teaching, and writing” (Farmer, 20). He stayed in jarrow for the rest of his life, making occasional trips to other parts of England to vistit other members of the church.

Among his contemporaries, Bede was well known and respected for his writing and his other intellectual pursuits. He died on the 26th of May, 735, and soon after his death was named a saint; with the day of his death celebrated as a feast day. Then in 1899, he was declared a Doctor of the Church, a title awarded by the Catholic Church to celebrate noteworthy contributions to theological, doctrinal, or other fields of learning, alongside such other scholars such as St. Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People

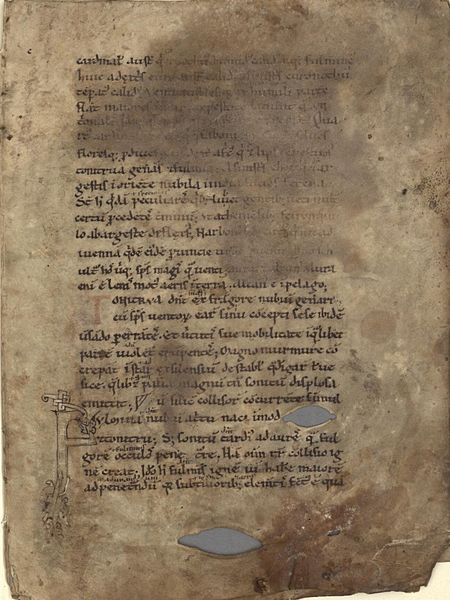

Bede’s most well-known work was the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. This seminal work, completed around 731, just a few years before Bede’s death, displays the advanced methodology that Bede is renowned for, which, for its time, was remarkable. It is this work that won Bede the title of “Father of English History”.

As a work of history, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People can be considered among the best examples of a medieval history, though Bede is somewhat prone to a “regional bias,” emphasizing events in his native Northumbria at the expense of some of the other realms in Britain (Farmer, 23). That said, it is clearly written and was both widely admired and widely copied. Bede’s historiographical influence stretched to the European Continent when Alcuin of York, who had studied under one of Bede’s own students, became a leading figure in the Carolingian Renaissance, a late 8th and early 9th century precursor to the later Renaissance. Then, 150 years after it was written, the Ecclesiastical History was translated from its original Latin into Old English, in support of the educational reforms of King Alfred the Great, the first king of England.

Bede’s Methodology

Aside from Bede, many other medieval histories were either dry recitations of events, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, which merely listed the events that occurred in a given year, or else were rather fanciful accounts, with no mention of where the author was getting their information, as in the case of Gildas with his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain). In comparison, Bede’s methodology is refreshingly modern in many ways.

The best examples of Bede’s historiographical contributions come from his Preface to the Ecclesiastical History. Here, he clearly states his sources explicitly “in order to avoid any doubts in the mind… of any who may listen to or read this history, as to the accuracy of what I have written” (Ecclesiastical History, 41). In doing so, Bede is on the same course that later historiographers would take, such as [Leopold von Ranke] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopold_von_Ranke), a 19th century German historian who insisted that historians should analyze and list their sources. By showing where he drew his information from, Bede allows later historians to critically analyze those sources including his own work and determine whether the information they related was accurate.

Some of Bede’s sources were narrative in form, stories told to him by an abbot from Canterbury named Albinus, which are the least reliable. On the other hand, in the early chapters, Bede relies almost entirely on primary sources such as letters to and from Pope Gregory I which was acquired from the papal archives in Rome by an Bede’s associate Nothelm. The last major type of source Bede had access to were eyewitness accounts, at most secondhand, of some of the later events he described. Recent events in Bede’s time such as the Synod of Whitby (664 A.D.), a council meeting of clergymen who met to discuss such subjects as the correct method of computing the date of Easter Sunday, would have been described to Bede by witnessing monks or those who knew the participants.

Bede clearly states his purpose in writing his history. For Bede, there are no questions about speculative philosophy of history, which in part poses the question of what history is for, of what purpose it serves. Bede provides a clear answer to the question of what history, or at least his history, is for. Dedicated to Ceolwulf, the then king of Northumbria, Bede states unequivocally that “if history records good things of good men, the thoughtful hearer is encouraged to imitate what is good: or if it records evil of wicked men, the devout, religious listener or reader is encouraged to avoid all that is sinful and perverse and to follow what he knows to be good” (Ecclesiastical History, 41). These words are renowned for their complexity, in determining the religious figures’ purpose, and poses insights into the Church.

Bede’s popularization of the anno Domini system of dating

In Bede’s time, the computation of dates, particularly of Easter, was an extremely important issue, and one that caused a great deal of controversy within the Cathlic Church. Differences in the method of determining Easter, for example, had often led to doctrinal conflict between various factions. One such conflict in England in the late 7th Century AD led to the Synod of Whitby, a council meeting of clergymen. This incident, and the issues that led to it, would have a great effect on Bede. He wrote at length about it in his Ecclesiastical History, and he would devote a great deal of effort in his other writings to determining the date of Easter specifically, and to the issues of dating in general.

In 725 A.D., Bede wrote De temporum ratione, (The Reckoning of Time), which among much else promoted the use of a novel system for dating years. A 6th-century monk named Dionysius Exiguus (c. 470 A.D.-544 A.D.) created this system for use in the scholarly world. In this system, years are numbered from the incarnation of Jesus Christ, and described with the phrase Anno Domini, “in the Year of our Lord”. This system of numbering years, either with the original abbreviation of “A.D.,” or with the secularized “C.E.,” for “Common Era”, is still in use around the world today.

Prior to Bede’s use of the AD system, and its ensuing popularization by Bede’s students, systems of numbering years were confused and complex. One common method was regnal dating, referring to years in reference to the reigns of kings or popes. At times, even Bede uses regnal dating, referring to events taking place in the “10th year of Pope Gregory’s reign” (Ecclesiastical 72) for example. This approach, however, has obvious limitations. This way of numbering years is inherently reliant on references to kings or other rulers, and if a modern-day historian is unfamiliar with these figures, their job will be much more difficult.

It’s worth pointing that the anno Domini system itself is just as reliant on a reference to a particular event, namely the incarnation of Jesus Christ, but the system has become so widespread, though the mechanisms of colonialism and later globalism, that the anno Domini system has become the de facto universal standard, used around the world. Much of the credit for its popularization can, without a doubt, be given to Bede, and to many of his students and contemporary admirers as well. These include Boniface, a notable monk and missionary to what is now Germany and the Netherlands, and Alcuin.

It is difficult for modern readers to understand how important Bede’s championing of Anno Domini and it’s ensuing well-nigh worldwide adoption is to the study of history, let alone to the pragmatic concerns of everyday life in the modern world. Prior to Bede, most countries and chronicles used their own systems of dating, counting years from the founding of a dynasty or else according to how long the current ruler had reigned. Thus, different accounts of the same events would place them in different years according to where each document was written, leading to dizzying confusion for modern readers. For many historical events in the early modern period, precise dates are scarce. The historical profession cannot overstate its gratitude to Bede for expanding the use of a universal system of numbering years, first in the Christian world, and later used across the globe.

Conclusion

Bede’s work, and his influence among the scholarly circles which were in his time dominated by the Catholic Church, and the monastery systems in particular, cannot be understated. While his practice of carefully listing and explaining his sources did not become widespread, in his own work it is a clear sign that historians were striving to better their works and methods before the Renaissance. Additionally, Bede’s other contribution to historiography, his promotion of the anno Domini system, should not be ignored when discussing his many achievements. It’s time for Bede to take his rightful place among those scholars who participated in the more gradual advancement of historiography throughout the medieval era, standing in stark contrast to the oft-invoked image of the so-called ‘Dark Ages.’ Far from being devoid of any intellectual advancement, Bede shows us that the epoch between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance was indeed replete with scholarly pursuit in Europe. It must also be acknowledged that Bede was not proposing or creating a new philosophy of History. His drive to list his sources was “not moved by ‘scientific’ motives but by his respect for the authority of the source and the awareness that… to distort a document would damage the truthfulness expected of a writer on sacred subjects” (Breisach, 96). His work was, of course, deeply informed by the Catholic Church of which he was a part. Bede’s philosophy of history would not have allowed him to challenge Biblical accounts, or indeed the accounts of earlier historians, as would become common place beginning in the Early Modern Period. Bede thus represents an incremental, rather than a paradigmatic, shift in historical thought.

Bibliography

Bede, the Venerable, Saint, David Hugh Farmer, R. E. Latham, Saint Egbert, the Venerable Bede Saint, and Abbot of Wearmouth Cuthbert. Ecclesiastical History of the English People: With Bede’s Letter to Egbert. Penguin Classics. London, England; New York, New York, USA: Penguin, 1990., 1990.

Bede, the Venerable, Saint, Calvin B. Kendall, Faith Wallis, and the Venerable Bede Saint. On the Nature of Things and, On Times. Translated Texts for Historians: V. 56. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2010., 2010.

Bede, and Faith Wallis. Bede, the Reckoning of Time. Translated Texts for Historians. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999.

Biggs, Fred, George Hardin Brown, Frederick M. Biggs, and Charles Wright. Bede Part 1. Sources of Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, & Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007., 2007.

Brown, George, and Frederick Biggs. Bede Part 2. Bede. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Brown, George H. Bede the Venerable. Twayne’s English Authors Series 443. Boston: Twayne Pub, 1987.

Brown, George Hardin. A Companion to Bede. Anglo-Saxon Studies: 12. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2009., 2009.

Burrow, J. W. A History of Histories: Epics, Chronicles, Romances and Inquiries from Herodotus and Thucydides to the Twentieth Century. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008., 2008.

Cheng, Eileen K. Historiography: An Introductory Guide. London: Continuum, 2012., 2012.

Hunter Blair, Peter. The World of Bede. Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990., 1990.

Kelley, Donald R. Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder. New Haven: Yale University Press, ©1998., 1998.

Killion, Steven B. “Bedan Historiography in the Irish Annals.” Medieval Perspectives 6 (January 1991): 20–36. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hlh&AN=53550490&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History. New York, NY: Routledge, 2003.

Wormald, Patrick, and Stephen David Baxter. The Times of Bede: Studies in Early English Christian Society and Its Historian. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2006., 2006.