Enlightened Historiography

“Enlightenment is man’s release from his self-incurred immaturity.”

The Enlightenment witnessed thinkers who used reason to critique the established structures of society. This criticism was also applied to the study of history. History of the Enlightenment cannot be understood without a fundamental understanding of philosophical concepts of the time. In this article Enlightenment thought and its effect on the study of history are examined.

A time of enlightened thought, a time of rational thought, a time of reason. A time that blurred lines between Philosophers and Historians. The Enlightenment was a time of profound change in intellectual thought in the 17th and 18th centuries. Like most significant eras, the Enlightenment provoked events that would have repercussions on society – the Enlightenment would go on to inspire the founding documents of The United States of America, the French Revolution and would play a significant role in shaping modern European politics and thought, and history will began to be written in differing ways; ways that society sill uses to this day. During the Enlightenment, history was approached more critically and with a desire to use the lessons learned to improve the human condition. This age of reason and logic was the culmination and pinnacle of human development. The Enlightenment didn’t happen on accident; it was strewed on by great thinkers, scientific revolution, and historians – history is the master science.

The Master Science

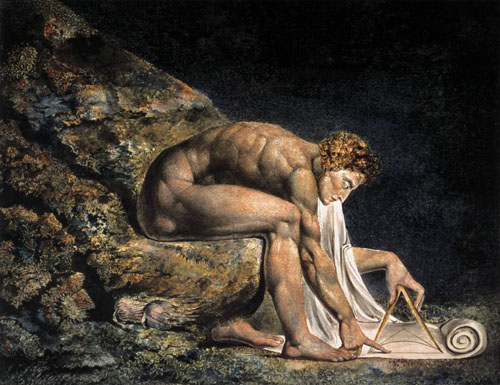

Before the turn of the 18th century, a scientific revolution was gaining prestige. Scientists were forming new ways of understanding the physical world around them, and the scientific method was beginning to become a staple way to observe the natural world objectively. Science, as a discipline that we can still recognize today, emerged in the late Renaissance, and it would ultimately shape the Enlightenment. This new way of dealing with things in a scientific way would spill over into other fields of study. Sire Isaac Newton was a highly influential scientist during the turn of the 18th century, and was a major player in the scientific revolution. All roads of modern historiography lead to this period. Newton’s most famous work Principia details what we still know today as the Laws of Nature – but not to be confused with Natural Law. This new way of rational thinking, from the scientific revolution, would pave the way for enlightenment thought and enlightened historians – which in many ways wrote history in many ways that is recognizable amongst the ways we know today. While the Enlightenment can be read as a major shift in thought, it still has and had detractors to common theory.

Enlightened Reason & Thought

Reason, in the context of the Enlightenment, is the ability to use facts, methods and logic to gain knowledge about the world. It becomes more important in academic pursuits than imagination, as a modern phlisopher defined, “Reason is contrasted with such hypostatized internal or external rivals as imagination, experience, passion or faith” (Flew, 300). During the Enlightenment reason comes to play a larger role in the study of history; ‘reasoned history’ sought to find the underlying causes of events. Why things happened became as much of an academic pursuit as what happened. There are some important concepts to understand when examining enlightenment thought. Humanism appeared during the Renaissance as a belief in human ability but coexisted with religious belief and faith. During the Enlightenment, Humanism changed and began to reject religion and faith. Humanism places humans and the belief in human goodness and achievement as supreme to divine beliefs. In humanism, individuals are primary, and humanity is compared to the individual. “Humanity is like individual members of the species” (Kelley, 217). Philology is the examination of the language and meaning behind the language of historical documents in a critical effort to examine the authenticity and original meaning of histories. Academics believed that there are rights that inherently belong to humans and are part of the human condition. The culmination of these beliefs can be seen during the French Revolution in 1789 with the rhetoric of inalienable rights i.e. life, liberty, property. The belief in these rights is described as Natural Law. Hobbes and Locke are considered founders of modern political philosophy. They debated about the social contract. Hobbes was an English philosopher who is known for his work Leviathan. Hobbes wrote Two Treatise on Government. They argued that individuals give up some freedoms and liberties to form societies and benefit from the order and protection that these societies provided. The state of nature is contrasted with civil society.

Access

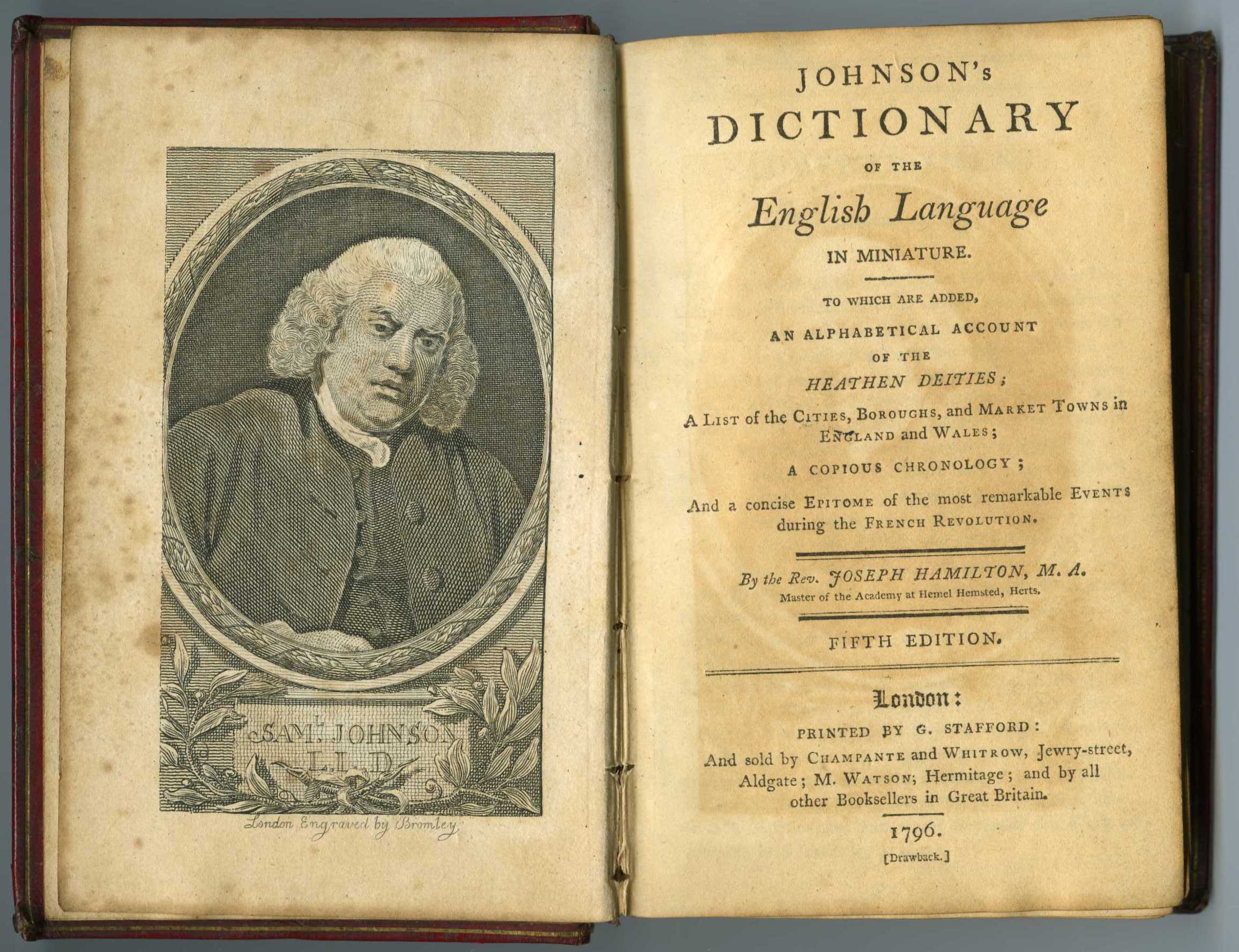

The Republic of Letters represents a significant shift in the access to academic discourse. The Republic of Letters was an international system of scholarship and criticism that spread the new ides through society. Scholars and philosophers sent letters, papers, and pamphlets to each other for discourse and debate on the important topics of the day. This enabled more access to the new ideas and debates of this time. Scholars could share ideas that were not easily shared in early time periods because of linguistic and geographic constraints. During the Enlightenment advances in the technologies of making books made books more accessible. The proliferation of the written word demanded categorization and organization. Samuel Johnson published his dictionary in 1755. The Johnson Dictionary became the preeminent dictionary of the next two hundred years.

Enlightened Thinkers

A prominent vision of the thinkers of this time is that of the French Philosophes, “fashionable and influential thinkers of the Enlightenment” (Flew, 267). The discourse of Enlightenment thought spread far beyond France. Through the Republic of Letters, books and resources, like dictionaries, we hear the voices of these thinkers through the past and wonder what they bought to history that was new. It is important to look at them individually for their contributions to the narrative and dialogue of historiography during the Enlightenment.

I think, therefore I am

Rene Decartes was one of the most influential men of the Enlightenment. Descartes wrote “Discourse on the Method”. In it he uses a form of reasoning where any idea that contains doubt is rejected as not representing the truth. Through this method of reasoning he concludes “Cogito, ergo sum” (Decartes, 2010, 15), I think, therefor I am. Vico argues that man can know better that which he creates than that which he observes.

Capital P Progress

Marquis de Condorcet had achieved much in his career. He was the secretary of the Académie des Sciences at a young age. The French Revolution changed that and he died in jail in 1794. He had supported the French revolution in the beginning; howeverm, he began to oppose it and had to hide from French authorities. While in hiding, he wrote “Sketch for an Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind.” Condorcet was influenced from a young age by his love of mathematics. He thought that history was more science than philosophy. “History is a matter of gathering and ordering facts and then showing ‘the useful truths that can be derived from connections and causality’” (Lemon, 188). Like Vico, Condorcet saw history in three stages. “The first runs from the darkness of an unknowable primitivism up to the development of language” (Bentley, 10). The second is from the advent of language to written alphabets, and the third is from alphabets to the Enlightenment. Condorcet believed that historical knowledge is learned to improve man’s condition. History is “man’s capacity to receive knowledge through his sense-experiences, accumulate and organize such knowledge in order to…achieve a more pleasing life” (Lemon, 188). Condorcet views these lessons from history as progress. Through this progress man challenges the status quo and seeks to gain equality from the traditional elites. “Progress occurs when intellectual innovations break down the resistance of traditional ways of doing things and changes the way people live” (Lemon, 88). It’s easy to see through this belief why Condorcet would have supported the French Revolution and how the political changes of his time influenced his view of history.

A Man Made History

Born in 1712 in Geneva, Jean-Jacque Rousseau disagreed with many of his contemporaries. Rousseau believed that the state of nature was one of happiness and equality. It was the need to form societies for protection that created inequality, materialism and unhappiness. In his “Discourse on Inequality”, Rousseau described the state of nature as “the happiest and most stable of our epochs…altogether the very best man could experience. In his discourse on the origins of inequality” (Lemon, 177). Hobbes and Locke both believed that the state of nature was one of violence and that modern societies provided equality and peace. To summarize, men formed societies as a means of protection, within these societies men developed their identities based on economic considerations, which in turn lead to the division of power and wealth. Men form civilized societies that lead to “egoism, exploitation, and insecurity for all involved, having stripped them of all independence, self-respect and genuine morality” (Lemon, 181). Rousseau believed that man created history through his decisions and was singularly responsible for its outcomes.

Universal Supremacy

French historians of the Enlightenment believed that the study of history was meant to go beyond the chronical of history and seek the human spirit. Voltaire was the Nom De Plum of Francois-Marie Arouet a preeminent French writer, historian, and philosopher who advocated for personal and religious freedoms. One of his most influential historical works is “Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations, published in 1756. Voltaire sought to write a universal history which gave supremacy to social history and arts and sciences rather than military campaigns. Voltaire’s primary historical concern was with “the progress of the spirit”. Although Voltaire sought to write an unbiased history he was critical of church histories and doctrines. Kelley says the Voltaire wrote history to further his own agenda. Voltaire sees the past as culmination in the perfection of the present.

Enlightened History

The study of history is an endless pursuit for truth. Truth is very hard to define, as one can never be sure if they know it or not objectively. Consuming history is an exhaustive task, for there are many recognizable and significant instances that have created sway in the major mindset of historians on the way of history. While this is true, it may seem inane to organize history by people and their texts. Inane in a sense that it is exhausting to read and read and read. But in truth it is notable to not only recognize but respect those who provoked wide arrays of thought in newer ways – in terms of the Enlightenment. The names and texts are important, but more notably the ideas and the provocation of thought that can only be recognized by respecting the dudes with their given texts. This is Rational History.

I Make Therefore I Know

Giambattista Vico was a respected Italian historian in the Enlightenment with many works under his belt. Although he was mostly subject to grammar schools, it is widely believed that he spent most of his time self-learning, and he was a lawyer by trade. His views on truth can be recognized throughout his works – most specifically Scienza Nuova – New Science. In his work, Vico described three ages of humanity: the divine, the heroic and the human. Vico believed that we can only observe absolute truth through creation or invention, echoing the scientific revolution, and that with imagination the historian allowed “the properly trained scholar to penetrate to the heart of this prehistorical darkness” (Kelly, 234). Truth being the most highly contested word to historians, understanding truth is fundamental to all historians’ views of the past. Vico was a Humanist, and he had “a fascination with the question of origions and the prehistorical ages of myth, barbarism, and a putative state of nature before civil society”1. Vico answered the question of “I think therefore I am” with “I make therefore I know”.2 This making is what history is all about. This sentence is very unclear- It’s its biggest deal. Making history. Writing history. And gaining a better understanding for the past and the world around us by looking through the eyes of not just larger trends, but focusing on a more humanist aspect, and in doing so showing that history is done for somebody, and that somebody is humans because ultimately humans write history. Vico believed that “those who make can understand in ways that mere observers cannot” — this statement Vico is directly disagreeing with Rene Decartes (Stanford, 156) . Ultimately, Vico was on a “the quest of a full historical meaning”.3 This historical meaning is what places Vico amongst Enlightenment historians - meaning & rational thought being essential to Enlightenment thought. Extracting meaning from things is important to the health of humanity, and being able to do it with history did work in creating a new identity, or at least in making history accessible into a way that is relatable.

The End of Rome

Gibbon loved Rome, or he hated it. Hard to say because, while he focused a lot of his energy and attention on Rome, he also wrote about the eventual fall of Rome and the aftermath. Either way, all roads of Gibbon lead to Rome. On a trip to Rome in 1764, Englishmen Edward Gibbon took on the challenge of writing a comprehensive history of the Roman Empire, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Being born in London, he spent most of his life there. Unfortunately his early life was plagued by illness. Gibbon, like the rest of the Enlightenment historians, took a different approach into writing or retelling history. Gibbon sought to use the new historical paradigm of seeking the deeper meaning behind historical events to explain the ‘why’, as well as he wanted to explain the fall of the Roman empire through barbarians and “unenlightened attitudes” of the Roman Catholic church. Gibbon’s history of Rome is a great example of the use of philology in history. He removed the sanctity of the church, and instead made claims that it was the work of man rather than the work of some supernatural entity. This was shocking as the dust began to settle about the protestant reformation. Gibbon focused all of his attention on primary resources when possible. He was a primary resource kind of guy. And while this is something recognizable today in history, it eluded a lot of history. Gibbon’s work put humans in human history, and he “believed he could recreate past entire by paying attention to the known sources and discovering new ones in artifacts” (Bentley, 14). Rome was and still is a historical powerhouse. It’s a big bully in historical contexts of things, and for good reason. Rome’s empire was huge to say the least. But Gibbon focused on things away from the cultural norm. Away from the Roman jurisdiction, and focused on the decay, the rot, the decline. And in doing so he doesn’t simply rewrite history, but, rather, retells history from a different angle. Because history demands to be told from several angels because it is a multidimensional beast. Gibbon’s history is also a first example of citation in academic history — he provides an example of a new introduction to history during the Enlightenment, which is the inclusion of eastern histories within the context of western historical traditions.

Father of Modern Sociology

There’s a reason why we call people the fathers of things. And regardless of the criticism that is associated, the simple implication of having a father of something creates a central ideological understanding of an individual to the wider society. Adam Ferguson was a prominent Scottish historian. He was educated in grammar schools and inspired by fellow humanists and humanists before him. His works deal with social aspects of man, and they illustrate humanity and its progressive nature. This focus can be noted in the title of his works: Essay on the History of Civil Society, Principles of Moral and Political Science, and so on. Adam Ferguson, the Father of Modern Sociology – whatever that means – told a story that focused differing psychological approaches to history. And in this way “the history of the individual is but a detail of sentiments and thoughts he has entertained in the view of his species”.5

The Enlightenment historians have a huge advantage over those that came before them. Why? How? They thought of themselves as rational thinkers and strived to do and create things in a sensible way. The history of the individual belongs to the individual. And the greater governing forces are administrators of liberty. Ferguson recognized the difference in Natural History or Natural Law with humans and their histories. But instead saw them as one in the same thing because humans exists in the greater context of nature, like nature is constantly surrounding the human. A humanist and progressive history like Ferguson’s is only possible with an Enlightenment background because it requires a lot of study of the human race, isolating individuals in their greater social frameworks – creating a more universal history. A history that is better understood by many. That will inspire many to think of themselves in different ways. One truly does know more about the past than the past knew about itself.

Historical Theatre

Johann Herder was a German historian – really a German man of all trades. He was a philopher, a poet, a critic, a historian, and so on. But it’s really hard to separate the historians from the thinkers and others during the Enlightenment - for they were all doing a lot of the same stuff. The thinkers of the Enlightenment speculated rationality and meaning. They were fortunate enough to have all previous histories at their disposal - to use and make sense of. In a way it was the study of the human race. Herder was born in Mohrungen, and lived a poor life. Having mostly educated himself, eventually he attended a university and was lucky enough to be a student of Kant. Herder was highly invested in nature, and he was extremely curious about how man interacted and lived with nature. And this combination was true for most of his works. He saw the harmonizing of things of philosophy and history and so on.

Again, the universality of this kind of history is prominent, and the deeper truth to these historians of the Enlightenment being closely associated with meaning is no accident. Because absolute truth is easier to identify with meaning. So, like the rest of the social sciences, history’s attempt to make meaning of things is an indicative part of the Enlightenment. And while these rather dense and allusive texts are seemingly confusing, the greater meaning exists through and around the metaphors of nature and so on.

What Actually Happened

The Enlightenment ends with Ranke. Leopold Ranke was a German historian, and a German historian he was. He grew up studying history and went on to lecture. Because of his religious background, his texts are highly influenced by his religious beliefs. His influence was so vast, it is easy to start history with Ranke’s name. It is easy to recognize and understand his thought processes because it is still an attractive way of doing history. He is known for his popular phrase – better said in German: “Wie es eigentlich gewesen”. Ranke’s ultimate goal was to stay objective as possible. And although he tries, his texts often contain sanctity.

____________

1 Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History: from Herodotus to Herder (Yale, 1998), 224.

2 Antonio Perez-Ramos, Francis Bacon’s Idea of Science and the Maker’s Knowledge Tradition (Oxford, 1988).

3 Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History, 223.

4 Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (New York, 1836), 1.

5 Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of Civil Society 5th ed. (London: T. Cadell, 1782).

6 Ibid.

7 Johann Gottfried Herder, Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Man (New York, 1800), 235.

Bentley, Michael. Modern Historiography: An Introduction. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Flew, Andrew. A Dictionary of Philosophy: Second Edition. New York: St. Martin Press, 1984.

Kelley, Donald R. Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Lemon, M.C. Philosophy of History. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Stanford, Michael. An Introduction to the Philosophy of History. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1998.

Kant, Immanuel, Political Writings H. S. Reiss Cambridge University Press, Jan 25, 1991.